33 Stars

The United States flag

The red, white and blue standard flying above ranks of blue clad troops, changed little during the course of the Civil War, 1861–1865.

When the war began a 34th state, Kansas, had just been admitted to the Union (January 29, 1861) and wouldn't officially join until July 4, 1861. Thirty-three-star flags were still common early in the war; one flew over Ft. Sumter when it was shelled, opening the war. The stars representing the seceded Confederate states were never removed from the U.S. flag, as President Abraham Lincoln maintained they were still states within the Union, albeit states in rebellion.

During the war two new states were admitted to the Union-West Virginia in 1863 and Nevada in 1864-so the U.S. flag boasted 36 stars by war's end. It also got a new nickname. When Union troops captured Nashville, Tennessee, in February 1862, an old shipmaster living there, Captain William Driver, brought out the large American flag he had hidden. Though it only had 24 stars-it had been given to Driver in 1831-it was raised above the Tennessee capital. He called the flag "Old Glory" and the name stuck.

Different versions of the flag arranged the stars in various patterns, from simple rows and columns to a star comprised of stars, with four stars in its center. Other designs included five stars circled around a single star, with the pattern repeated five times; in four places, a single star was placed, to create a 34-star flag.

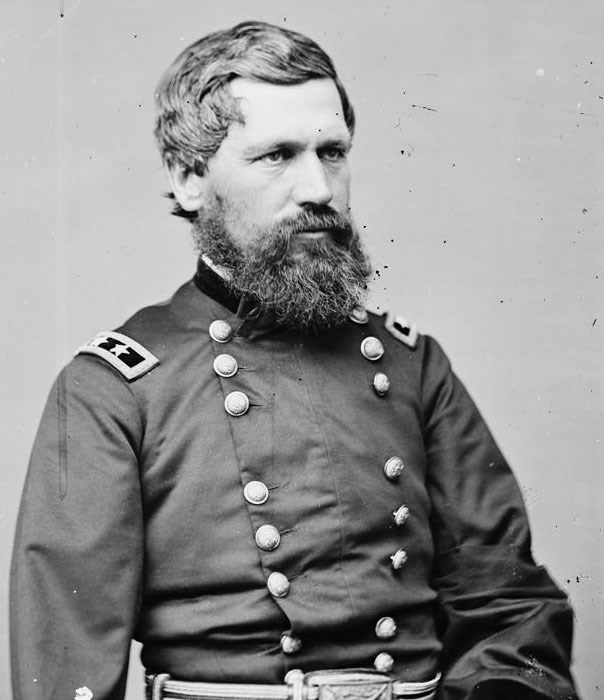

Best known for leading the Army of the Potomac to victory over Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Meade is a fascinating historical figure who remains lesser-heralded than the Rebel generals he fought like Lee and Stonewall Jackson. He also stands in the shadow of his Union compatriots like Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman and even Phillip Sheridan.

Despite winning the largest battle ever fought in the Western Hemisphere, few Americans even know his name

Here are some interesting facts most people probably don't know about Meade.

- He wasn't even born in the United States:

Despite being one of the greatest American generals of his age, Meade was actually born abroad. His father, Richard Worsam Meade, was a wealthy Philadelphian who was serving as a U.S. naval agent in Cadiz, Spain when George was born in 1815. In fact, Meade the Elder had loaned money to the Spanish monarchy to help fund its fight against Napoleon, who had occupied the country in 1808. But when Richard requested repayment after Bonaparte's downfall, he was thrown in jail. Later, under the terms of 1819 Florida Purchase Treaty, the U.S. government acquired the future Sunshine State as settlement for all American citizens' financial claims against Spain. Despite acquiring the new territory for nothing, Washington never did compensate Spain's many U.S. creditors. As a result, the Meade family fortune was lost. - He served closely with his famous future foe:

So many Civil War generals first faced hostile fire in America's 1846 war with Mexico. Meade was one of them. In fact, he was brevetted first lieutenant for gallant conduct during the Battle of Monterey. Remarkably, Meade and his future Gettysburg opponent, Robert E. Lee, traveled together on the steamship Petrita with General Winfred Scott to Veracruz Bay. The expedition sought a location to land U.S. troops. While scouting one stretch of promising coastline, Mexican cannon balls fell perilously close to the ship. If the enemy artillerymen had slightly better aim, neither men might have survived to meet each other in battle years later. - He made a name for himself building lighthouses:

At West Point, Meade was trained to be a topographical engineer. In the 1850s, the army assigned him to design and erect lighthouses. He oversaw their construction on coral reefs off the Florida coast at Carysfort Key, Sand Key and Sombrero Key, which are familiar sights to Florida boaters to this day. Meade designed one particularly elegant lighthouse at Jupiter Inlet, Florida. Others can be found in Absecon and Barnegat New Jersey, and Brandywine Shoal in Delaware Bay. He even designed a new lighthouse lamp to replace a more complicated but popular French style. Meade's innovation was successful and ended up being used in other American lighthouses. In 1856, the army assigned Meade to supervise a survey of the Great Lakes. He oversaw detailed mapping of Lake Huron and Saginaw Bay before the outbreak of the Civil War. - His men gave him the nickname the "Old Snapping Turtle":

Meade was a perfectionist with a volatile temper. He could pitch into people when they made even the slightest mistake. Although respected for his intelligence, boundless energy and courage in battle, his staff didn't like being subjected to his sharp tongue. - He rose steadily through the ranks:

Meade began the war as a brigadier general. Wounded at the Battle of Glendale in June 1862, he fought in all of the Army of the Potomac's major battles. After Antietam, he was promoted to division commander and following Fredericksburg, he became commander of the Fifth Corps. When Lee invaded Pennsylvania in June of 1863, Fighting Joe Hooker offered his resignation. Lincoln accepted and placed Meade in charge of the Army of the Potomac. The three previous commanders, George McClellan, Ambrose Burnside and Hooker had all been defeated by Lee. It would be up to Meade to break the losing streak. - He saved the Union cause at Gettysburg:

Although many remember the repulse of Pickett's Charge on Gettysburg's third and final day as the pivotal moment of the battle, it was Meade's actions the afternoon before that really saved Union army, and perhaps even the entire war. Amid the fighting on July 2, Meade positioned the Third Corps under General Dan Sickles on the Federal left at Cemetery Ridge. Dissatisfied with the ground he was assigned, Sickles ignored orders and moved his 10,000-man force more than half a mile forward, leaving Little Round Top, and the entire Union flank, dangerously exposed. When Lee attacked through the Peach Orchard and the Wheatfield, Sickles' troops fought bravely but were overwhelmed. With the Union line suddenly in grave danger, Meade decisively rushed in troops from all over the battlefield to keep the Confederates from rolling up the Yankee line. Meade remained on the frontlines in the saddle as enemy bullets whizzed all around him. One even struck his trusty warhorse, Old Baldy – one of four times the animal would be wounded during the war. - Many blamed him for Lee's escape after Gettysburg:

Meade's pursuit of the retreating Confederate army was hindered by torrential rain storms that hit the day after Gettysburg. The downpour also bedevilled Lee, as the swelling Potomac was suddenly unfordable. After the Union cavalry destroyed a Rebel pontoon bridge, Lee's men were caught with their backs to the river. They prepared fortifications on a ridge facing mostly open farmland. Before attacking, Meade held a council of war with his corps commanders. Most were against a frontal assault across the soggy ground. Fearing a repeat of Fredericksburg, Meade delayed for a day. But when he was ready to advance, Lee was gone. The river had receded enough to be forded and the Confederates had built a new pontoon bridge. Lincoln was disconsolate, believing Meade had been too hesitant to attack. "Our army held the war in the hollow of their hand and they would not close it," the president lamented. - After Gettysburg, he was investigated by Congress:

Meade's insubordinate general, Sickles, lost a leg to a shell at at Gettysburg. After recuperating, he asked to be restored to command of the Third Corps. When Meade refused, Sickles went before the Committee on the Conduct of the War in Washington and falsely testified that the general wanted to retreat and not fight at Gettysburg. He even had an anonymous article published in The New York Herald, the country's largest circulation paper, claiming that Meade ineptly handled the army during the battle and that only his own unauthorized advance foiled Lee's plans. Sickles' false narrative damaged Meade's reputation. - He made enemies in the press:

All of the major Northern newspapers sent war correspondents to cover the Army of the Potomac. But when one Philadelphia Inquirer reporter published rumours that Meade had wanted to retreat after the Battle of the Wilderness, the outraged general expelled the offending journalist from camp. Stinging from the rebuke of one of their own, several other newsmen conspired to write only negative stories about Meade. Henceforth, Grant would get the credit for the Army of Potomac's victories while Meade's name only appeared in articles where reporters could blame him for defeats.

| Union Commanders | |

|---|---|

| https://www.nps.gov/gett/learn/historyculture/union-commanders-at-gettysburg.htm | |

| General John Buford The commander of a cavalry division in the Army of the Potomac, John Buford's troops encountered the head of a Confederate column on June 30th near Gettysburg. It was Buford who decided to stay in the area overnight and wait for the Confederates to return the following day. His choice would set the stage for the Battle of Gettysburg that began the following day, July 1, 1863. |

| General John Reynolds One of the most highly respected and dynamic Union generals serving in the Army of the Potomac, Reynolds commanded the First Army Corps. Reynolds had reportedly declined an offer to command of the army and recommended fellow Pennsylvanian, George Gordon Meade. Having rushed his infantry to the battlefield on July 1, the general was encouraging his soldiers in a swift counterattack on Confederates in a grove of woods adjacent to the McPherson Farm when he was instantly killed. His loss from was sorely felt throughout the army. |

| General Abner Doubleday This New York officer took command of the First Corps after the death of its leader, General Reynolds. He deployed his experienced troops on a line west of Seminary Ridge and held the ground until overwhelming numbers forced his depleted regiments to retreat through Gettysburg. After the war he authored Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, his memoir and history of the two great battles that were his last with the Army of the Potomac. |

| General Winfield S. Hancock Inspiring, bold, and daring, Hancock proved to be an outstanding field commander at Gettysburg. Meade sent Hancock as his representative to Gettysburg on July 1, where he took command of the chaotic situation. The general was everywhere the action was on July 2 and played a prominent role in sending troops to threatened areas. He nearly lost his life while directing a counterattack against Pickett's Virginians on July 3rd, an injury that would plague him for the rest of his life. |

| General Oliver O. Howard Commanding the Eleventh Corps, this one-armed general took charge of the field after the death of Reynolds and secured Cemetery Hill as the final Union position for which he later received a congressional thanks. Howard later served in the Atlanta Campaign with General Sherman and in 1867 worked to establish a school for African Americans in Washington, DC, known today as Howard University. |

| General Henry Hunt In charge of the Union artillery, his disciplined use of Union batteries played a major role in defeating the Confederate battle plans for July 2 and 3. Hunt's obsession with complete control of the army's artillery would conflict with infantry commanders at Gettysburg and elsewhere during the war. |

| General Daniel E. Sickles A colorful politician turned general, Sickles led his Thirds Corps to Gettysburg, determined not to allow the Confederates to hold higher ground. His controversial move forward from Cemetery Ridge on July 2nd resulted in the bloodiest day of fighting, costing the general most of his corps and a leg. Awarded the Medal of Honor for his services at Gettysburg, he sponsored the 1895 legislation that made the battlefield a national military park. |

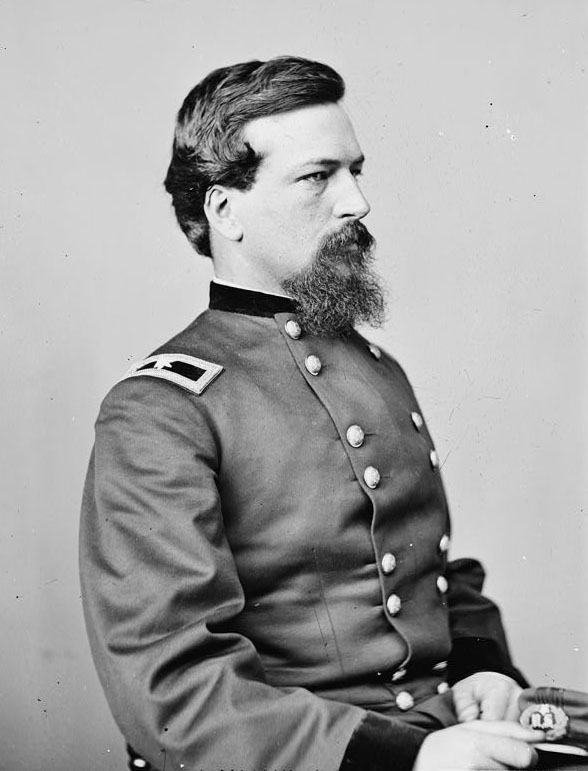

| General Gouverneur K. Warren Serving as Meade's Chief of Engineers, Warren was surveying the Union left when he spied Confederate forces moving around the Union left and toward Little Round Top. Realizing its importance, he rushed troops to the hill's defense, which ultimately saved the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. That evening, the exhausted Warren slept through Meade's Council of War. He later commanded the Fifth Corps in the Overland Campaign until a conflict with his superiors caused an abrupt end of his field command in 1865. |

| Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain A school teacher by trade, Chamberlain had risen to the rank of colonel of the 20th Maine Infantry by Gettysburg. His battle tested veterans were pitched into a desperate fight with the 15th Alabama Infantry on July 2nd and despite nearly overwhelming odds, won the day at Little Round Top thanks to their colonel's stubborn guidance. By war's end, Chamberlain was a major general and placed in charge of accepting the Confederate surrender parade at Appomattox Court House. |

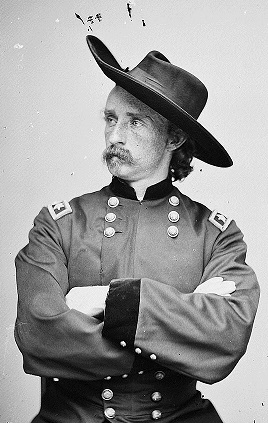

| General George A. Custer Long before he would meet his fate at Little Big Horn, Custer, as a newly appointed brigadier general, commanded a brigade of Michigan cavalry regiments. On July 3, 1863, he displayed his dynamic ability to lead men in battle, leading regiment after regiment in desperate charges that eventually won the day in the cavalry battle east of Gettysburg. |

| Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing This 22 year-old West Pointer commanded Battery A, 4th United States Artillery. His battery was destroyed in the cannonade prior to Pickett's Charge though Cushing chose to remain on the field with his lone surviving cannon, which he served against the Confederate infantry attack until shot dead at his post. "Faithful unto death", his fanactical devotion to duty helped turn the tide at Gettysburg. In 2010, the United States Army approved a request to award him the Congressional Medal of Honor. |

| Doctor Jonathan Letterman As Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, his skills at organization and support were unequaled. The task of treating countless wounded in and around Gettysburg was left up to his undermanned staff that worked diligently to save thousands of wounded Union and Confederate soldiers. Many convalesced at "Camp Letterman", the general field hospital east of Gettysburg, before transfer to permanent hospitals in the North. |

| Alexander S. Webb A newly appointed brigadier general, Webb was placed in command of the "Philadelphia Brigade" during the march to Gettysburg. During Pickett's Charge on July 3rd, his troops met and threw back the Confederate breakthrough at the Angle. His dynamic leadership made a difference in the Union defense even though he was so new to command that many of the soldiers in the brigade did not know who he was. |

| Lieutenant Frank A. Haskell A Union staff officer at Gettysburg, Haskell was a model soldier and disciplinarian who was in the center of the Union line on July 2nd and 3rd where he witnessed most of the climactic events of the battle. He described his experiences in a lengthy letter to his brother that to this day is one of the most descriptive and eloquent battle narratives ever written. Unfortunately, Haskell was killed in battle the following year. |

Regiment Approximately 350 men

Brigade Two to six regiments

Division Two to four brigades

Corps Two to four divisions

Army Two or more corps