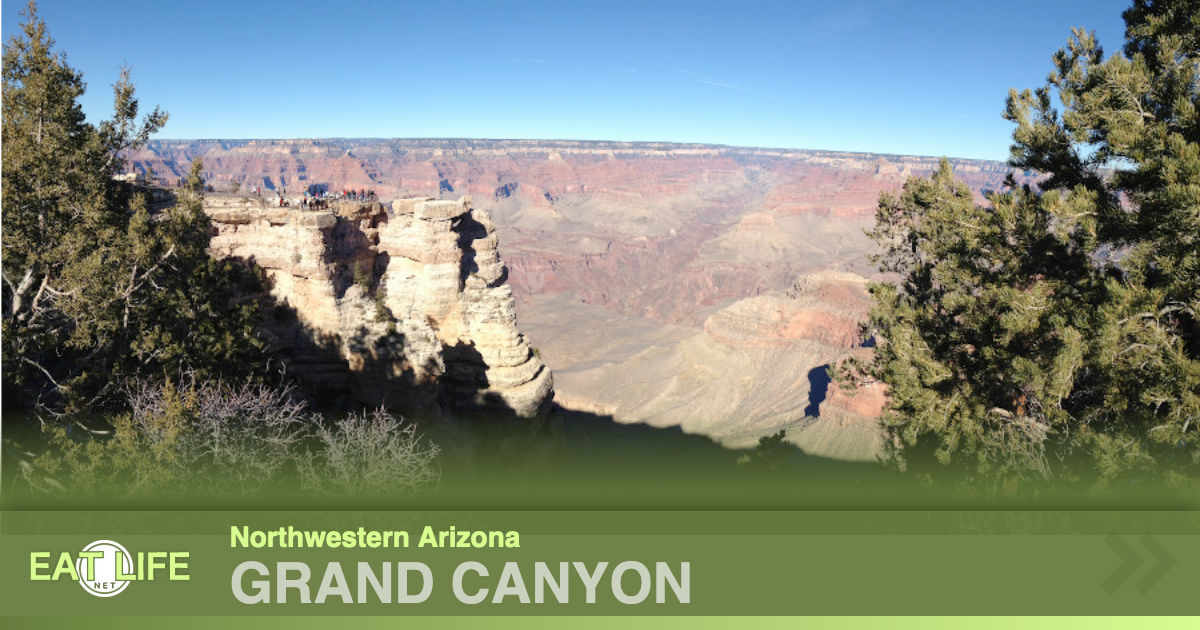

Grand Canyon is considered one of the finest examples of arid-land erosion in the world. Incised by the Colorado River, the canyon is immense, averaging 4,000 feet deep for its entire 277 miles. It is 6,000 feet deep at its deepest point and 18 miles at its widest.

Grand Canyon National Park:

- Is a World Heritage Site, encompasses 1,218,375 acres and lies on the Colorado Plateau in northwestern Arizona.

- The land is semi-arid and consists of raised plateaus and structural basins typical of the southwestern United States.

- Drainage systems have cut deeply through the rock, forming numerous steep-walled canyons.

- Forests are found at higher elevations, while the lower elevations are made up of a series of desert basins.

- It offers an excellent record of three of the four eras of geological time,

- A rich and diverse fossil record,

- A vast array of geologic features and rock types, and numerous caves containing extensive and significant geological, paleontological, archeological and biological resources.

- The Park contains several major ecosystems. Its great biological diversity can be attributed to the presence of five of the seven life zones and three of the four desert types in North America. The five life zones represented are the Lower Sonoran, Upper Sonoran, Transition, Canadian, and Hudsonian. This is equivalent to traveling from Mexico to Canada.

Over 1,500 plant, 355 bird, 89 mammalian, 47 reptile, 9 amphibian, and 17 fish species are found in park.

The story begins almost two billion years ago with the formation of the igneous and metamorphic rocks of the inner gorge. Above these old rocks lie layer upon layer of sedimentary rock, each telling a unique part of the environmental history of the Grand Canyon region.Rock deposition:

About 2 billion years ago igneous and metamorphic rocks were formed. Then, layer upon layer of sedimentary rocks were laid on top of these basement rocks.That the bottom layer was formed first, and every subsequent layer was formed later, with the youngest rocks on the top. In geology, this is referred to as the principle of superposition, meaning rocks on the top are generally younger than rocks below them.

Another important principle is the principle of original horizontality. This means that all the rock layers were laid horizontally. If rock layers appear tilted, that is due to some geologic event that occurred after the rocks were originally deposited.

Then, between 70 and 30 million years ago, through the action of plate tectonics, the whole region was uplifted, resulting in the high and relatively flat Colorado Plateau.Colorado Plateau uplift:

The Kaibab Limestone, the uppermost layer of rock at Grand Canyon, was formed at the bottom of the ocean. Yet today, at the top of the Colorado Plateau, the Kaibab Limestone is found at elevations up to 9,000 feet. How did these sea floor rocks attain such high elevations?Uplift of the Colorado Plateau was a key step in the eventual formation of Grand Canyon. The action of plate tectonics lifted the rocks high and flat, creating a plateau through which the Colorado River could cut down.

The way in which the uplift of the Colorado Plateau occurred is puzzling. With uplift, geologists generally expect to see deformation of rocks. The rocks that comprise the Rocky Mountains, for example, were dramatically crunched and deformed during their uplift. On the Colorado Plateau, the rocks weren't altered significantly; they were instead lifted high and flat.

Just how and why uplift occurred this way is under investigation. While scientists don't know exactly how the uplift of the Colorado Plateau occurred, a few hypotheses have been proposed. The two currently favored hypotheses call for something called shallow-angle subduction or continued uplift through isostacy.

Finally, beginning just 5-6 million years ago, the Colorado River began to carve its way downward. Further erosion by tributary streams led to the canyon's widening.How did the Colorado River carve such a big canyon?

The Colorado River has been carving away rock for the past five to six million years. Remember, the oldest rocks in Grand Canyon are 1.8 billion years old.The canyon is much younger than the rocks through which it winds. Even the youngest rock layer, the Kaibab Formation, is 270 million years old, many years older than the canyon itself.

Geologists call the process of canyon formation downcutting.

Downcutting occurs as a river carves out a canyon or valley, cutting down into the earth and eroding away rock.Downcutting happens during flooding. When large amounts of water are moved through a river channel, large rocks and boulders are carried too. These rocks act like chisels, chipping off pieces of the riverbed as they bounce along.

Several factors increase the amount of downcutting that happens in Grand Canyon: the Colorado River has a steep slope, a large volume, and flows through an arid climate.

Still today these forces of nature are at work slowly deepening and widening the Grand Canyon.A dynamic place:

Weathering and erosion are ongoing processes. If we were to visit Grand Canyon in another couple million years, how might it look?For one, it would be wider; we may not even be able to see across it anymore. Much of Grand Canyon's width has been gained through the erosive action of water flowing down into the Colorado River via tributaries. As long as water from snow melt and rain continues to flow in these side drainages, erosion will continue.

In a few million years, Grand Canyon also may be a bit deeper, though the canyon isn't getting deeper nearly as fast as it is getting wider. The rocks through which the river is currently downcutting are hard, crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks, which are much stronger than the sedimentary rocks resting above them. More importantly, the river's gradient has decreased, such that it has less power to battle with the hard rocks.

Finally, the river's elevation near Phantom Ranch, a popular hiking destination in the canyon, is just 2,400 feet above sea level. Because sea level (0 ft.) is the ultimate base level for all rivers and streams, upon reaching sea level, the Colorado River will be done downcutting.

[]

[https://www.nps.gov/grca/learn/nature/grca-geology.htm]

What is a Valley?

- A valley is a landform characterized by a low-lying area of land surrounded by high areas, such as mountains or hills. Valleys can be a wide variety of shapes and sizes. They are either erosional features, carved by water or glacial ice, or structural features, caused by rifting.

What is a Canyon?

- A canyon is a type of erosional valley with extremely steep sides, frequently forming vertical or nearly vertical cliff faces.The term "gorge" is often used interchangeably with "canyon" and generally implies a smaller, particularly narrow feature.