During the 1968 campaign, Nixon promised to bring about an honorable end to the war in Vietnam. Both as President-elect and immediately after taking office, he took action to try to jump-start peace negotiations.

But North Vietnam was unwilling to compromise and South Vietnam refused to make concessions.

Nixon, for his part, was not going to abandon America's ally.

In response, President Nixon developed a multi-faceted approach to ending the war.

- He increased military action while beginning to decrease American troop levels.

- He crafted an elaborate diplomatic strategy to open and improve relations with both the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union in order to decrease their military and monetary support for North Vietnam

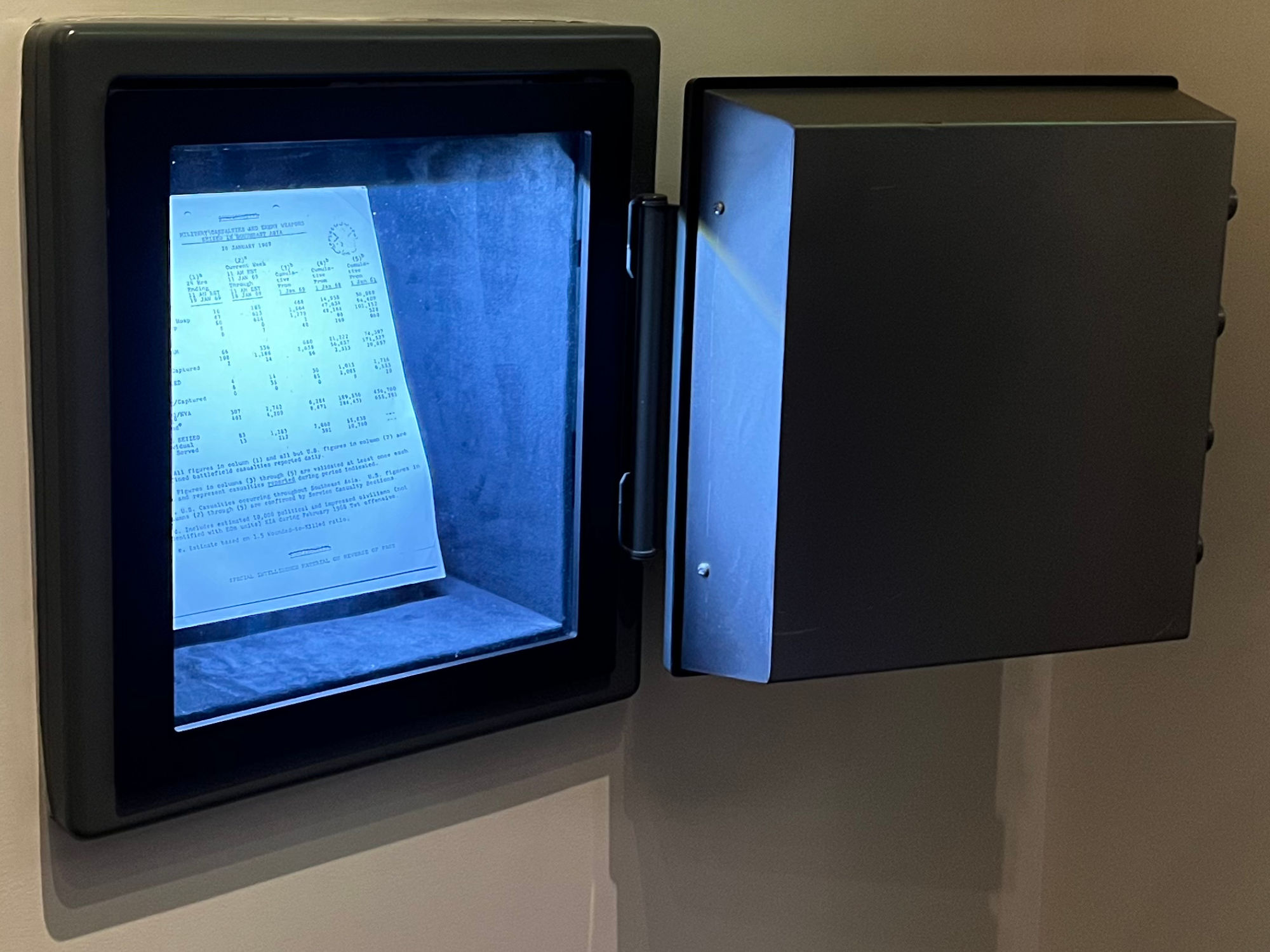

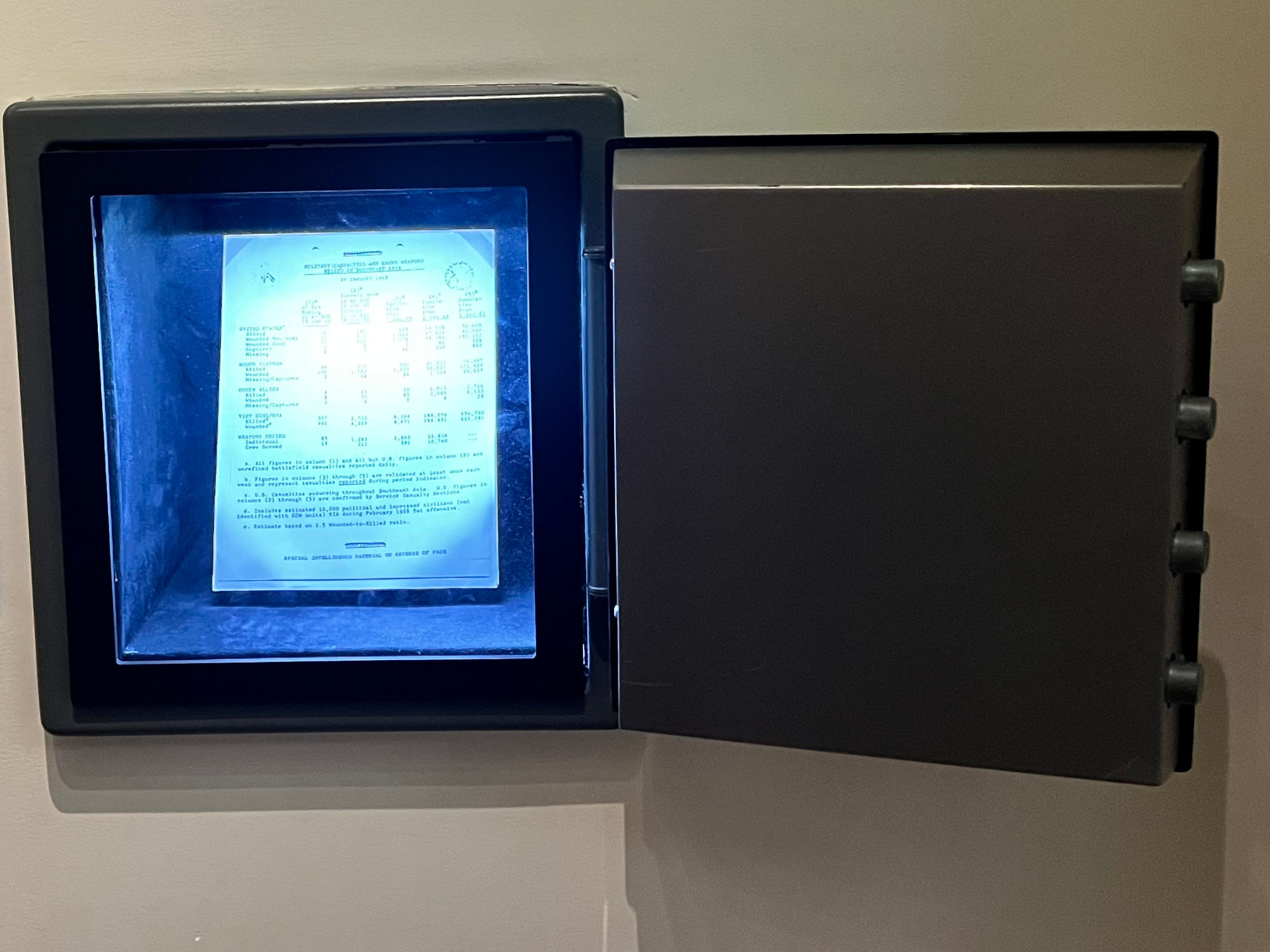

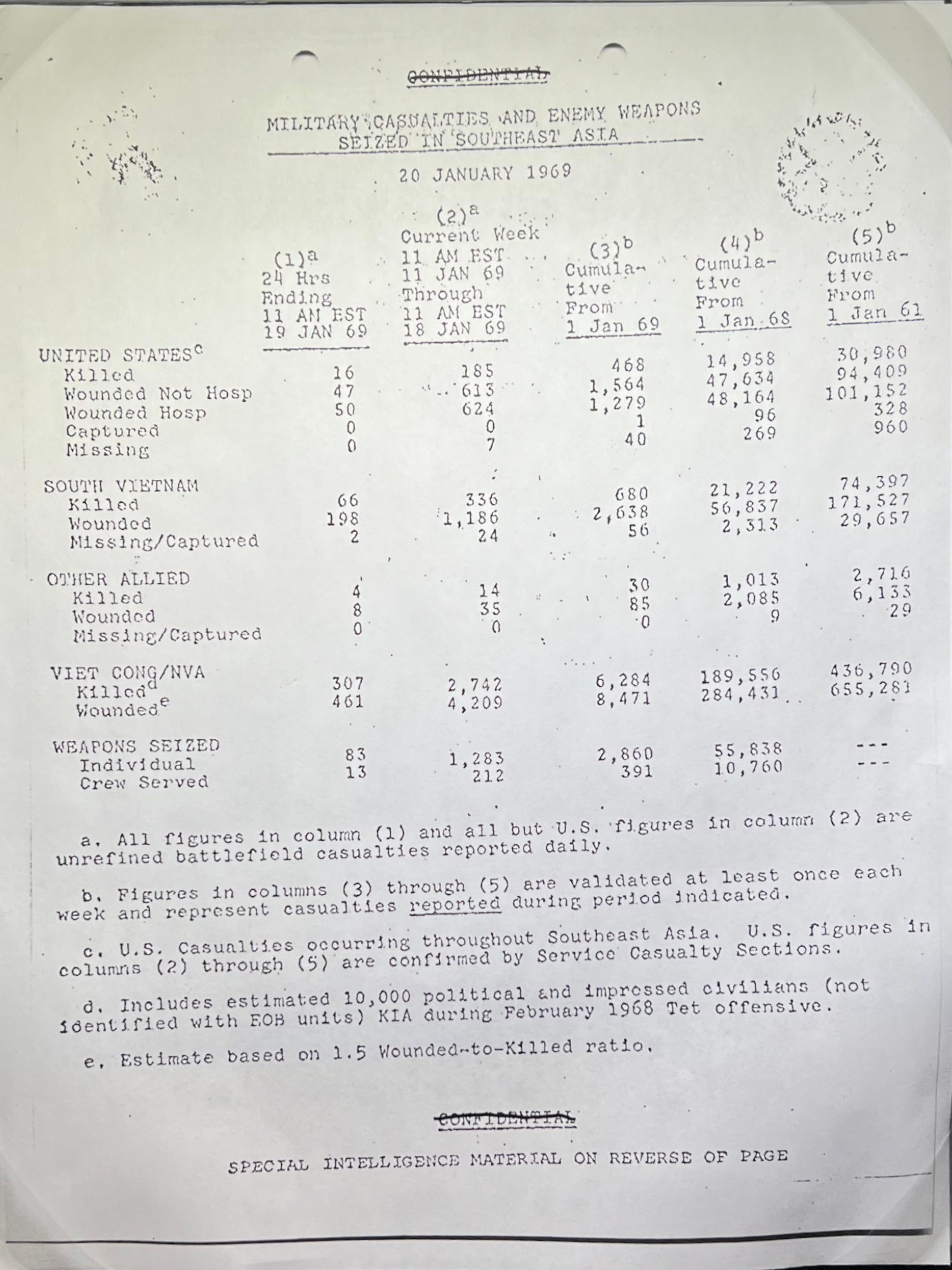

I slept only about four hours my first night in the White House, and was up at 6:45 a.m. While I was shaving, I remembered the hidden safe that Johnson had shown me during our visit in November. When I opened it, the safe looked empty. Then I saw a thin folder on the top shelf. It contained the daily Vietnam Situation Report from the intelligence services for the previous day. Johnson's last day in office.

I quickly read through it. The last page contained the latest casualty figures. During the week ending January 18, 185 Americans had been killed and 1,237 wounded. From January 1, 1968, to January 18, 1969, 14,958 men had been killed and 95,798 had been wounded. I closed the folder and put it back in the safe and left it there until the war was over, a constant reminder of its tragic cost.

Beginning in 1950, the United States had gradually ramped up its role in the Vietnamese conflict.

- President Harry S. Truman sent a small number of military advisors

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent money and equipment

- President John F. Kennedy sent 16,000 American troops as advisors

- President Lyndon B. Johnson, by the end of 1968, 550,000 Americans were fighting in Vietnam.

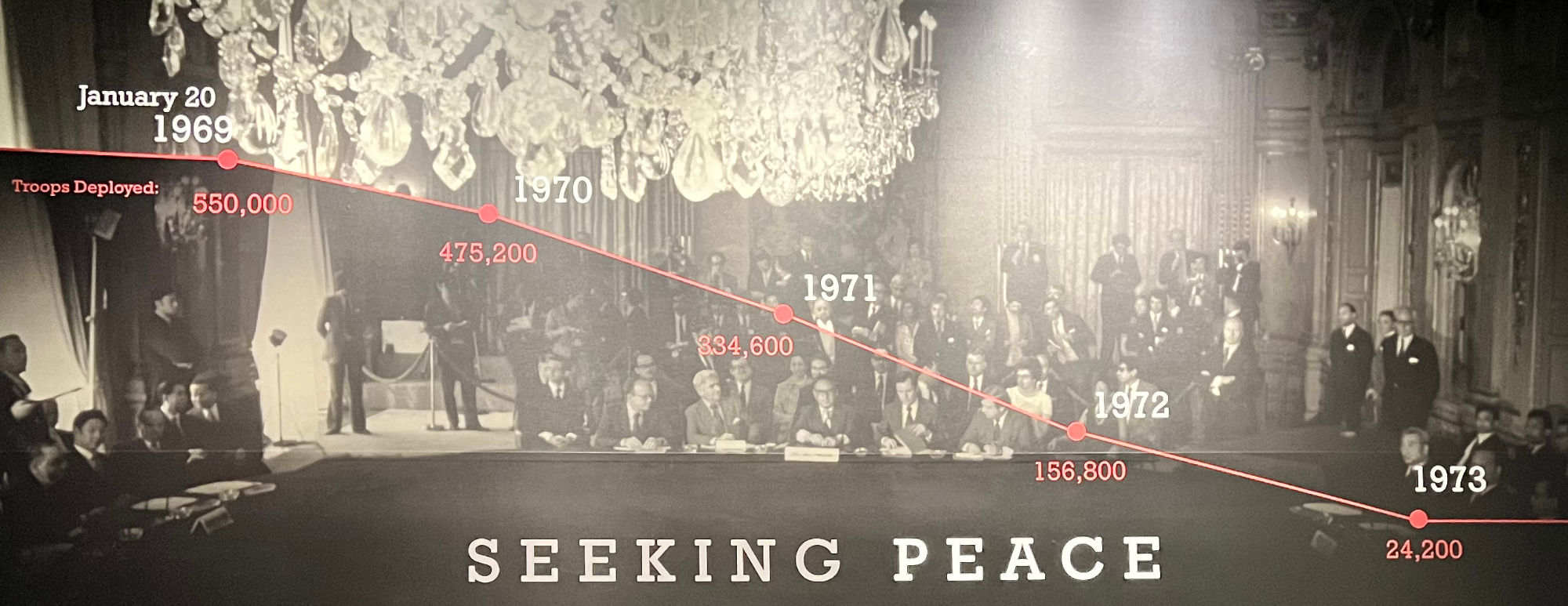

This was the situation Richard Nixon inherited when he took the Presidential oath of office on January 20, 1969. But Nixon was determined to achieve the "honorable peace" he pledged during the campaign.

He was ready to negotiate with the Communist North Vietnamese government and eventually settled on two conditions during the course of the negotiations.

- Although he realized the United States supported a South Vietnamese government under Nguyen Van Thieu, an imperfect ally struggling with internal corruption, Nixon would not abandon Thieu by accepting Hanois demand for Thieu's removal.

- Although Nixon initially insisted on mutual withdrawal by both U.S. and North Vietnamese forces from South Vietnam, he would eventually decide not to end the US military presence until all American prisoners of war had been returned.

We simply cannot tell the mothers of our casualties and the soldiers who have spent part of their lives in Vietnam that it was all to no purpose. - 1969

It is not the easy way. It is the right way. It is a plan which will end the war and serve the cause of peace - not just in Vietnam but in the Pacific and in the world. - November 3, 1969

- 1969: 550,000

- 1970: 475,200

- 1971: 334,600

- 1972: 156,800

- 1973: 24,200

| 1968 & 1969: | |

|---|---|

| While peace talks had been ongoing in Paris since 1960, by the end of 1969 the only agreement that has been reached was on the shape of the conference table. | |

| Late 1968: | Richard Nixon is elected President and begins private communications with Hanoi proposing discussions toward a settlement. North Vietnam's response - requiring total American withdrawal and overthrow of the South Vietnamese government - is unacceptable to the United States. |

| March 1969: | President Nixon orders the start of Operation Menu, a secret bombing campaign aimed at communist bases in Cambodia. |

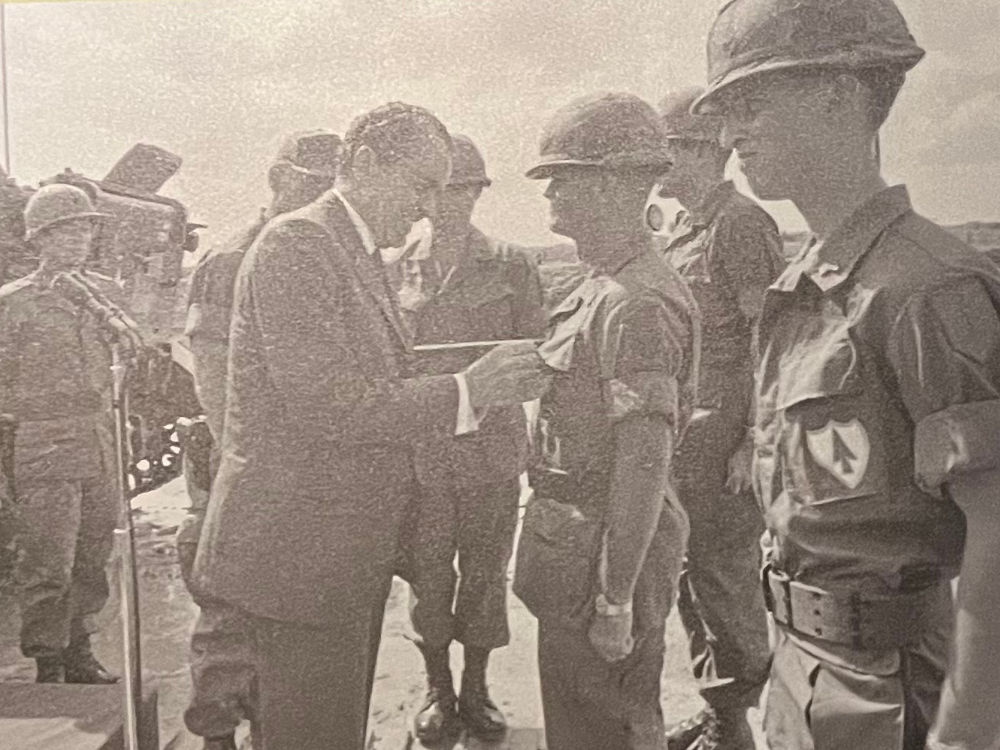

| June 1969: | President Nixon meets with President Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam on Midway Island and announces immediate withdrawal of 25,000 American troops. |

| July 1969: | President and Mrs. Nixon make an unannounced visit to Vietnam. It is the first time a First Lady travels to an active war zone. |

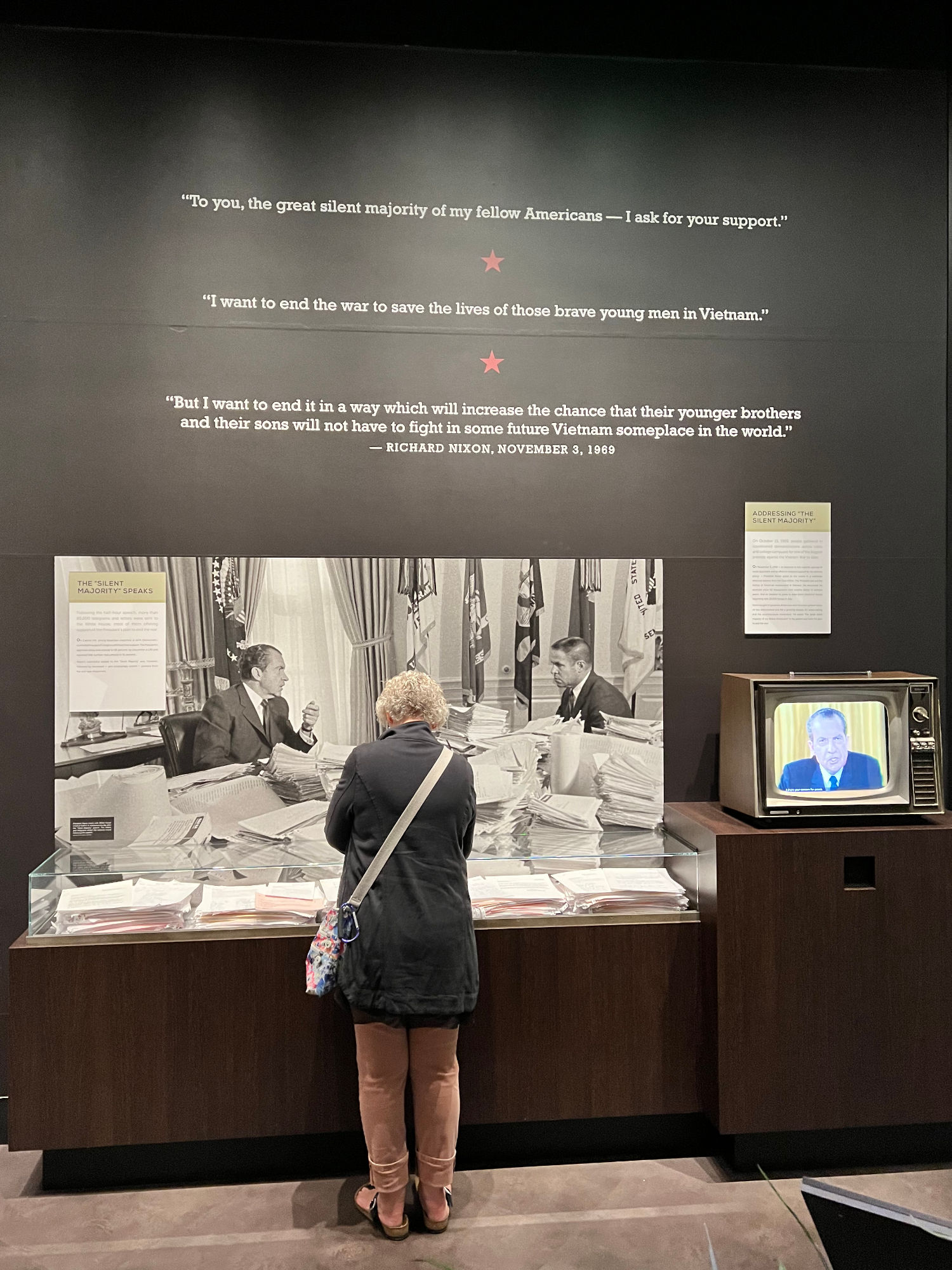

| October 15, 1969: | Millions of people across the nation and world participate in the Moratorium to End the War in a coordinated anti-war rally across more than 300 cities and college campuses worldwide. On November 3, President Nixon responds with his "Silent Majority" speech. |

| November 12, 1969: | The My Lai massacre story published in U.S. newspapers. |

| December 1969: | Throughout the 1960s, all American men age 18 and over, unless qualified for deferment, are eligible to be drafted into the military. Drawing on a system established during World War II, Nixon institutes a draft lottery in which conscriptions were based on drawing numbers, which were assigned to draft-eligible men by their birth date. |

| VIETNAM WAR | |

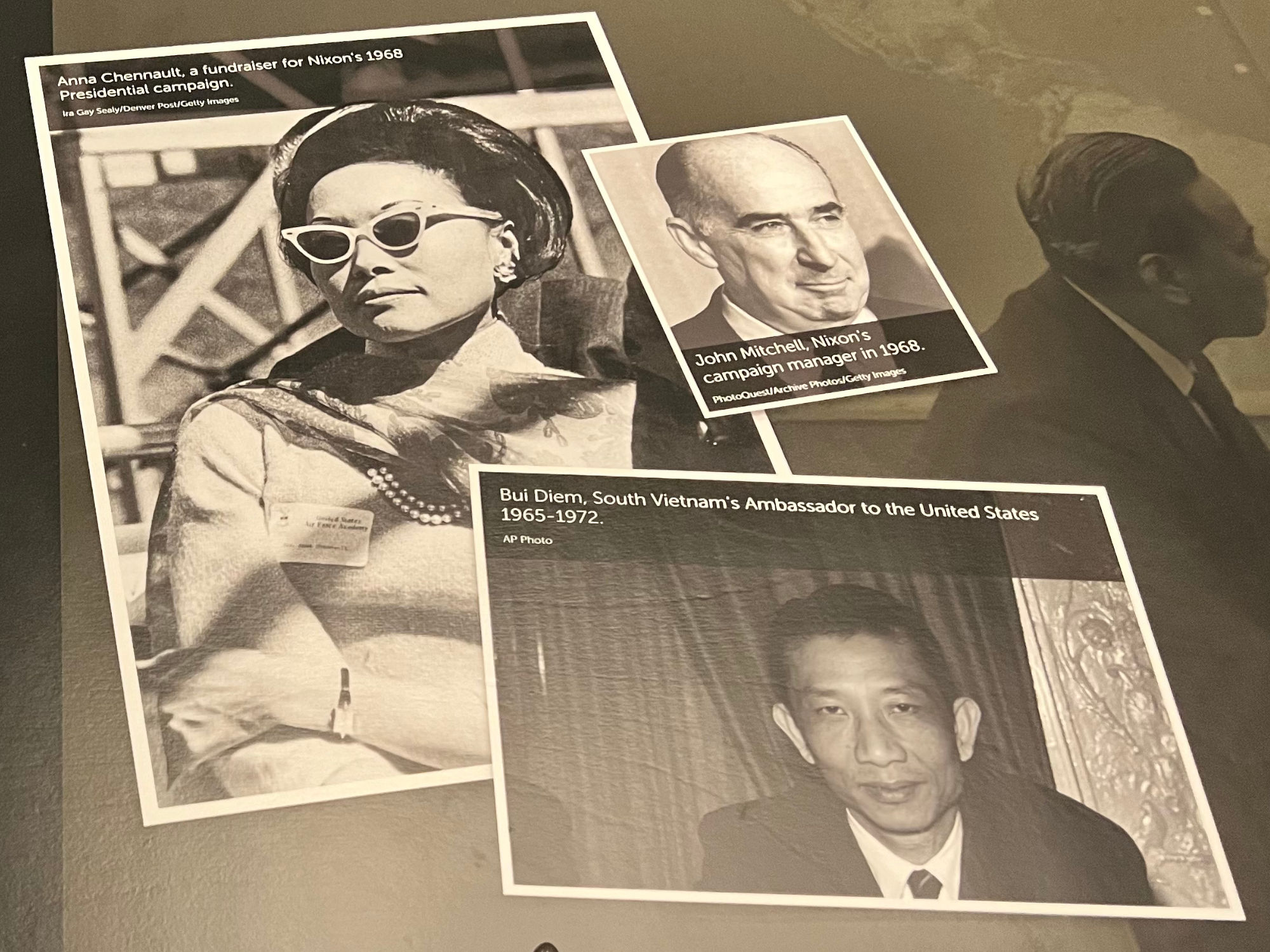

In 1968, the South Vietnamese followed the American Presidential campaigns with great interest. They had reason to believe that Nixon, who had a reputation as a strong anti-communist, would make a staunch ally against North Vietnam. Conversely they feared that a Humphrey victory would lead to a quick withdrawal of American troops, leaving South Vietnam on its own.

A few days before the election, President Johnson announced a halt to the bombing on North Vietnam, a move which some viewed as an October surprise intended to bolster Humphrey's campaign.

At the same time. Johnson ordered surveillance on the South Vietnam embassy and on Anna Chennault, a fundraiser for Nixon's campaign. He had received a tip that someone in the Nixon campaign was attempting to interfere with the peace negotiations.

Chennault, who claimed to be "the sole representative between the Vietnamese government and the Nixon campaign headquarters," was recorded delivering a message to the South Vietnamese ambassador from her unidentified "boss" - "the message was that he was to "hold on, we are gonna win."

Nixon denied any involvement in, or knowledge of, Chennault's activities, but there remains an ongoing controversy, and contemporary historians continue to debate the evidence on both sides.

- President Nixon meets with the soldiers of the First Infanty Division in Vietnam

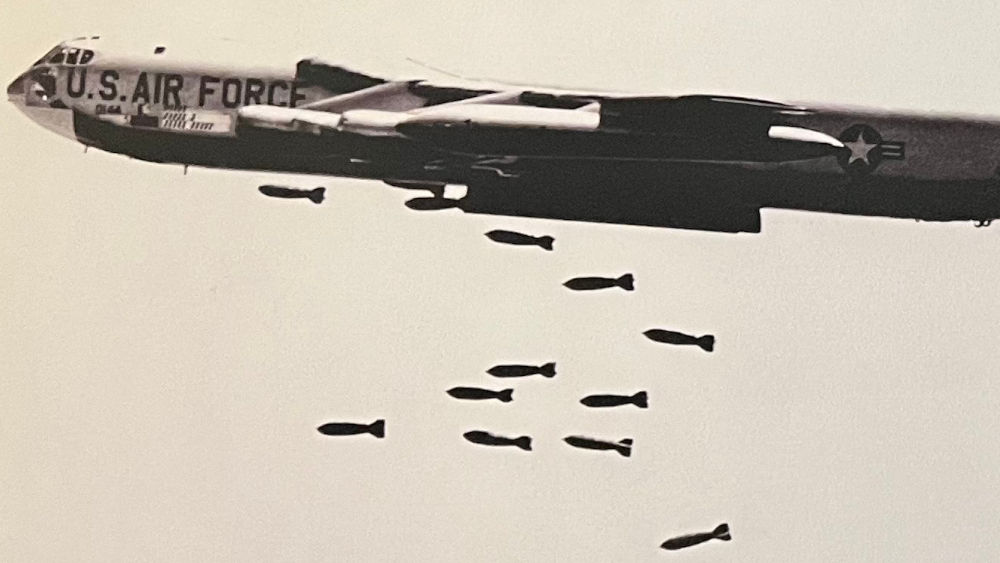

- A B-52 bomber drops conventional bombs over Vietnam

Hit occupying Communist forces who were using Cambodia as a sanctuary with a bombing campaign, code-named Operation Menu, to prevent more American and allied casualties.

- While the campaign was intended to be secret to spare Cambodia's Prince Sihanouk criticism for allowing bombing of foreign troops in his country as well as to prevent public and Congressional outrage, it was exposed after two months.

The North Vietnamese, despite the fact that we were adhering to the conditions of the bombing halt initiated by President Johnson in October 1968 ... were violating whatever conditions they were supposed to agree to. They were shelling cities. They were infiltrating more troops, and ... they were sending in great numbers of combat forces into the Cambodian sanctuaries. The net result of all that was to increase our casualties. - 1983

- President Nixon pins a Distinguished Service Cross medal on a soldier of the First Infantry Division in Vietnam - July 1969

Employ a strategy of "Vietnamization" - which meant increasing support and training for South Vietnam's forces to enable them to take on greater responsibility - while withdrawing American troops at the same time.

The defense of freedom is everybody's business - not just America's business. And it is particularly the responsibility of the people whose freedom is threatened. In the previous administration, we Americanized the war in Vietnam. In this administration, we are Vietnamizing the search for peace. - 1969

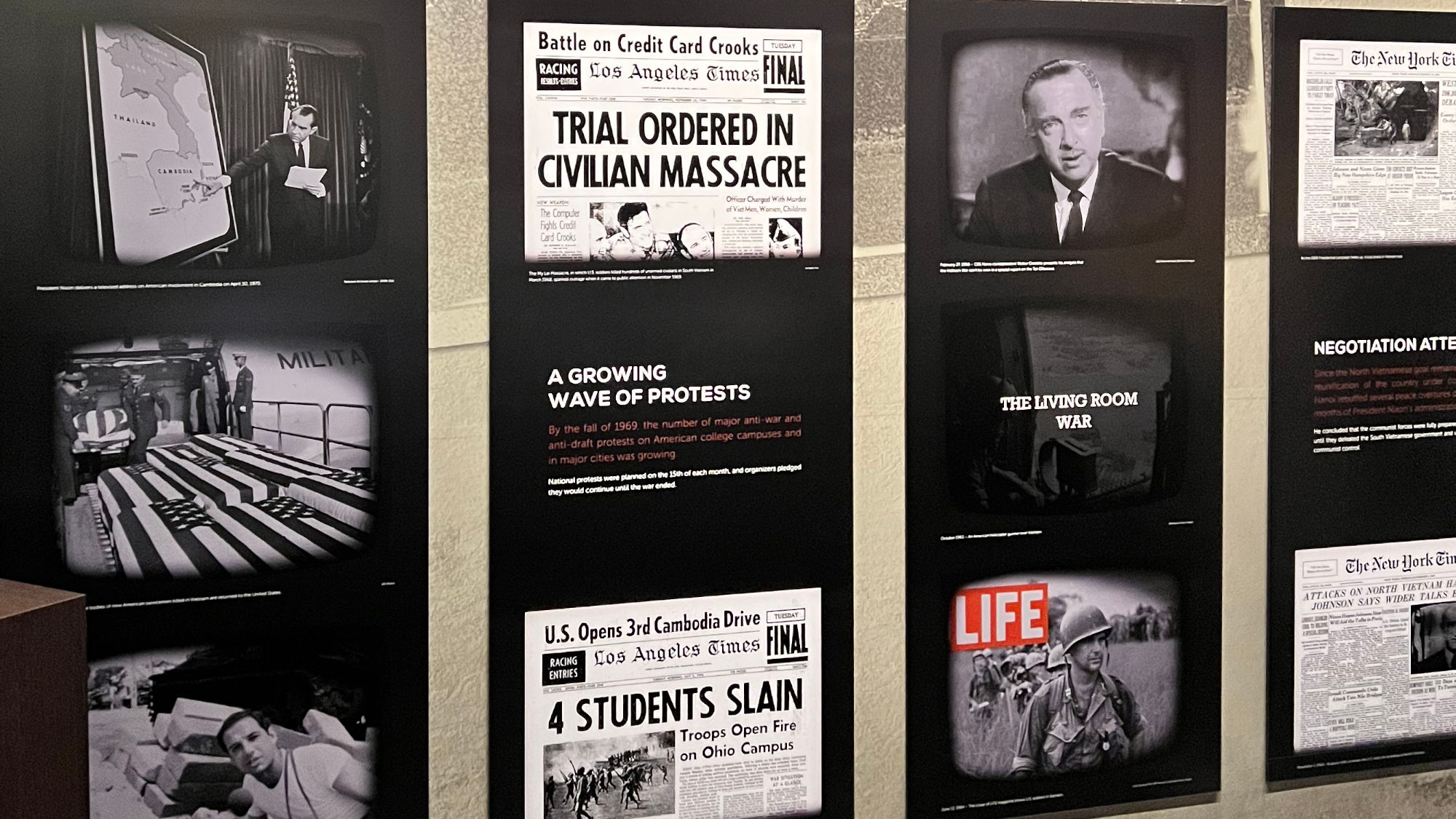

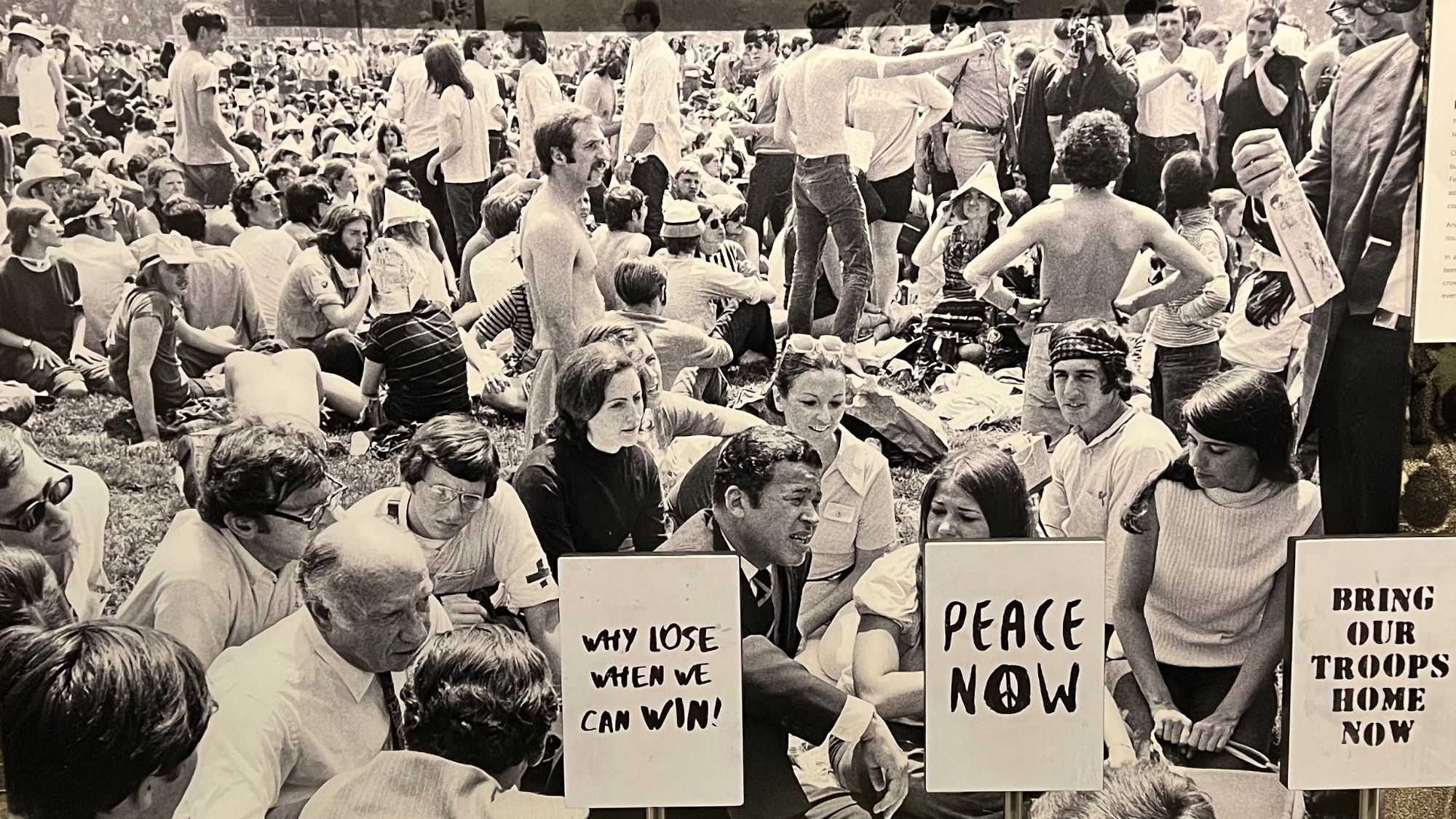

By the fall of 1969, the number of major anti-war and anti-draft protests on American college campuses and in major cities was growing.

- National protests were planned on the 15th of each month, and organizers pledged they would continue until the war ended.

Negotiation Attempts

Since the North Vietnamese goal remained centered on reunification of the country under communist rule, Hanoi rebuffed several peace overtures during the early months of President Nixon's administration.

- He concluded that the communist forces were fully prepared to continue the war until they defeated the South Vietnamese government and unified Vietnam under communist control.

The revelation of the cover-up of the My Lai massacre added to the intensity of the protests. In March 1968, a company of U.S. soldiers had killed the majority of the population of the South Vietnamese hamlet. The story was not revealed until November 12, three days before the November protests. Demonstrations occurred across the country - and the world - with participants from a broad spectrum of the population.

On November 15, a second moratorium demonstration was held. Some quarter of a million people gathered in Washington, DC, to protest the country's involvement in Vietnam. The crowds were mostly peaceful. However, when a radical splinter group broke off and began to throw bottles and burn American flags, police responded with tear gas.

One of the most dangerous assumptions in a democratic society is to conclude that only the President, the Cabinet, and the generals are competent to make judgments in the national interest. I regret the President has not seen the demonstrations as an opportunity to unite rather than divide the country.

- October 17, 1969

I recognize that some of my fellow citizens disagree with the plan for peace I have chosen. Honest and patriotic Americans have reached different conclusions as to how peace should be achieved.

- November 3, 1969

The question is not whether Johnson's war becomes Nixon's war ... The great question is: How can we win America's peace?

- November 3, 1969

On Capitol Hill, strong bipartisan majorities in both Democratic-controlled houses of Congress affirmed their support. The President's approval rating rose sharply to 68 percent; by December a CBS poll reported that number had jumped to 81 percent.

Nixon's successful appeal to the "Silent Majority" was, however, followed by increased - and increasingly violent - protests from the anti-war movement.

To you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans — I ask for your support.

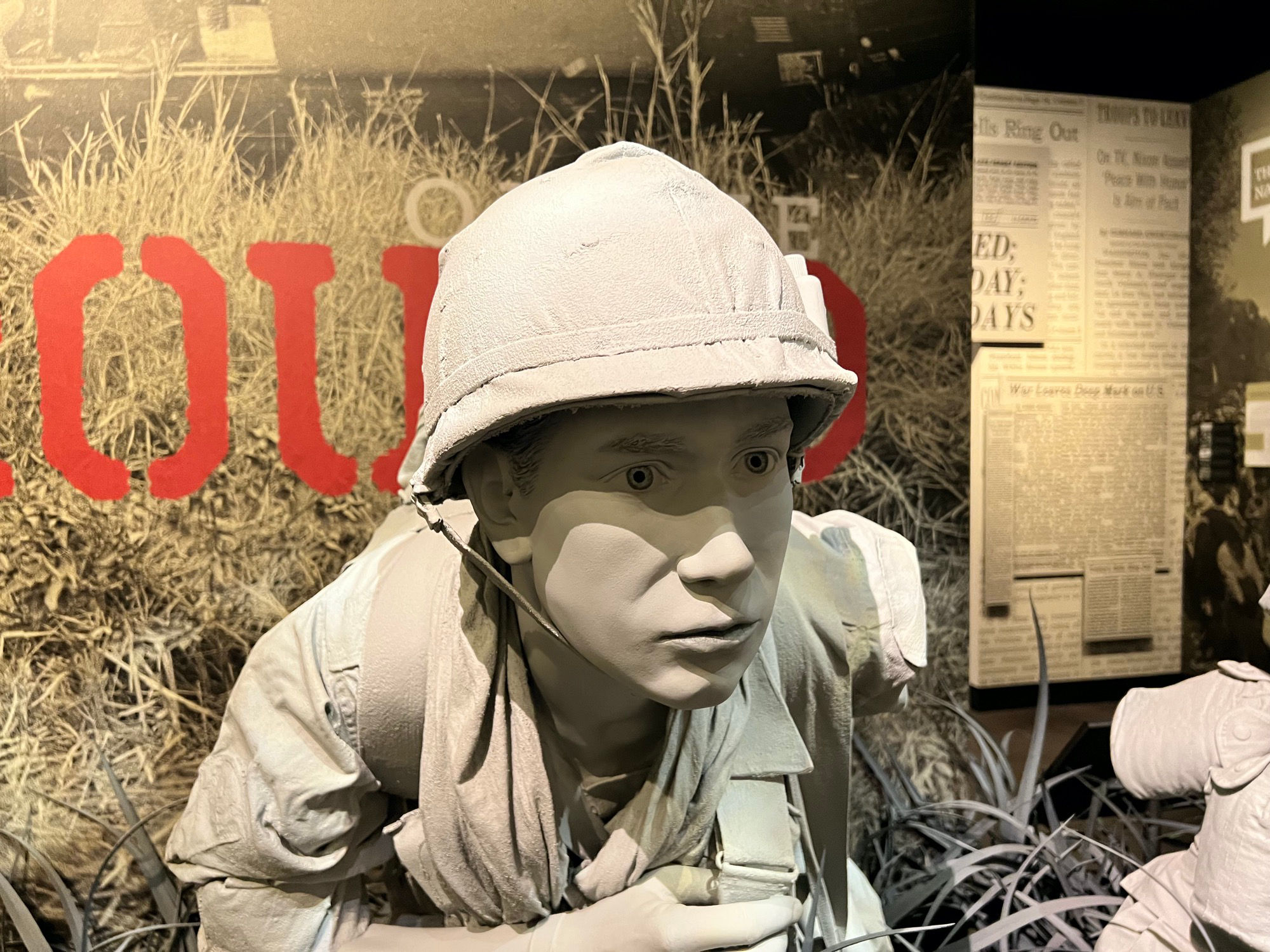

I want to end the war to save the lives of those brave young men in Vietnam.

But I want to end it in a way which will increase the chance that their younger brothers and their sons will not have to fight in some future Vietnam someplace in the world.

- November 3, 1969

| 1970: | |

|---|---|

| Peace talks in Paris remain deadlocked. The United States insists that all North Vietnamese troops must depart South Vietnam, while North Vietnam refuses to deal with the current South Vietnamese government led by President Thieu. | |

| February 1970: | Nixon's National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger begins ongoing secret one-on-one talks outside of Paris with Le Duc Tho, Politburo member and special advisor to the head of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam delegation at the Paris negotiations. |

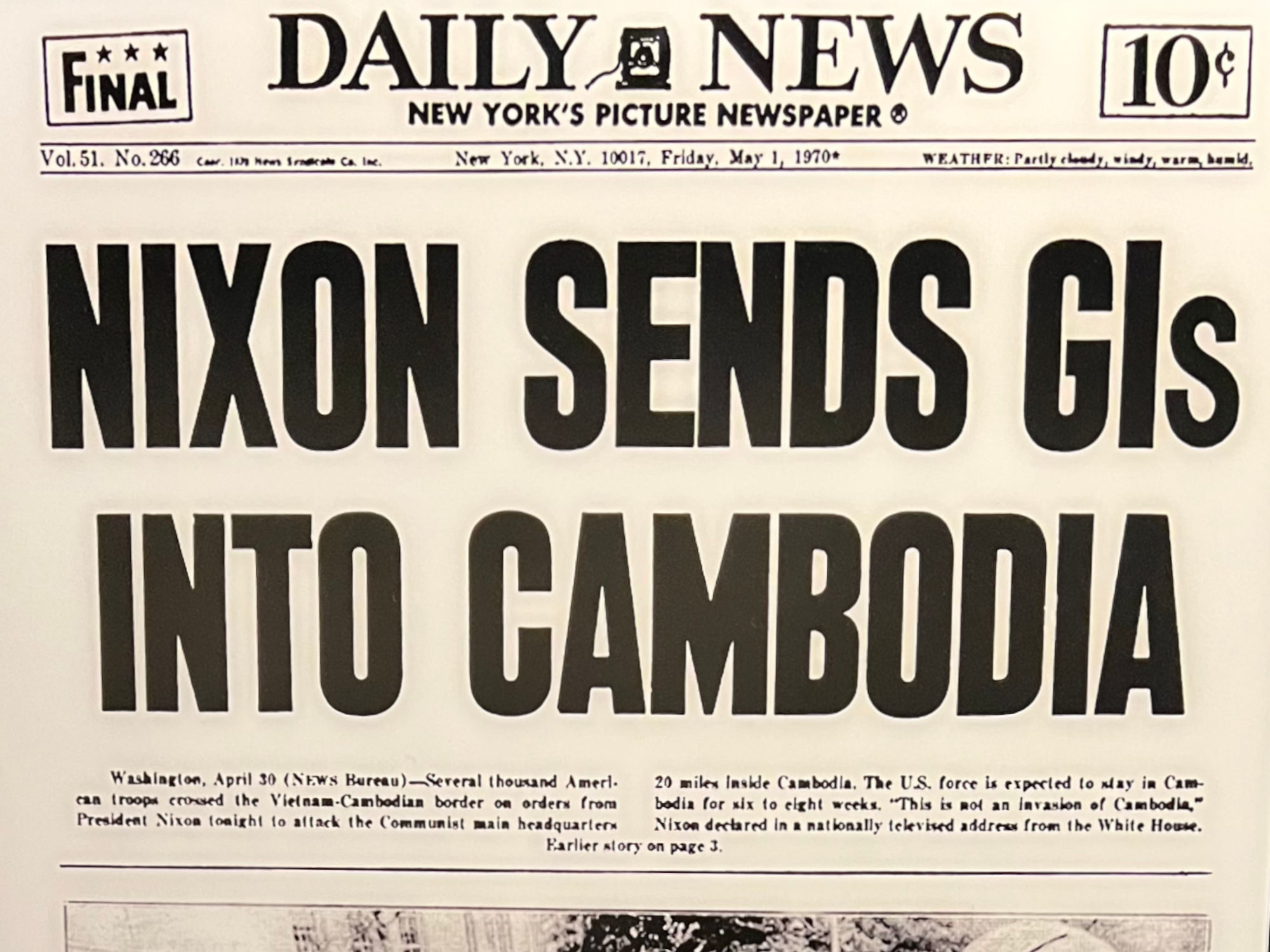

| April - May 1970: | South Vietnamese and American troops move into Cambodia to locate and eradicate the elusive Central Office of South Vietnam (COSVN), destroy enemy bases, and capture enemy weaponry. |

| May 4, 1970: | A protest against the U.S. incursion into Cambodia turns to tragedy at Kent State when members of the Ohio National Guard open fire on the crowd of student protesters and four are killed. |

| VIETNAM WAR | |

- May 1, 1971 - President Nixon's announcement that he was sending troops into Cambodia spurs a fresh round of protests on campuses.

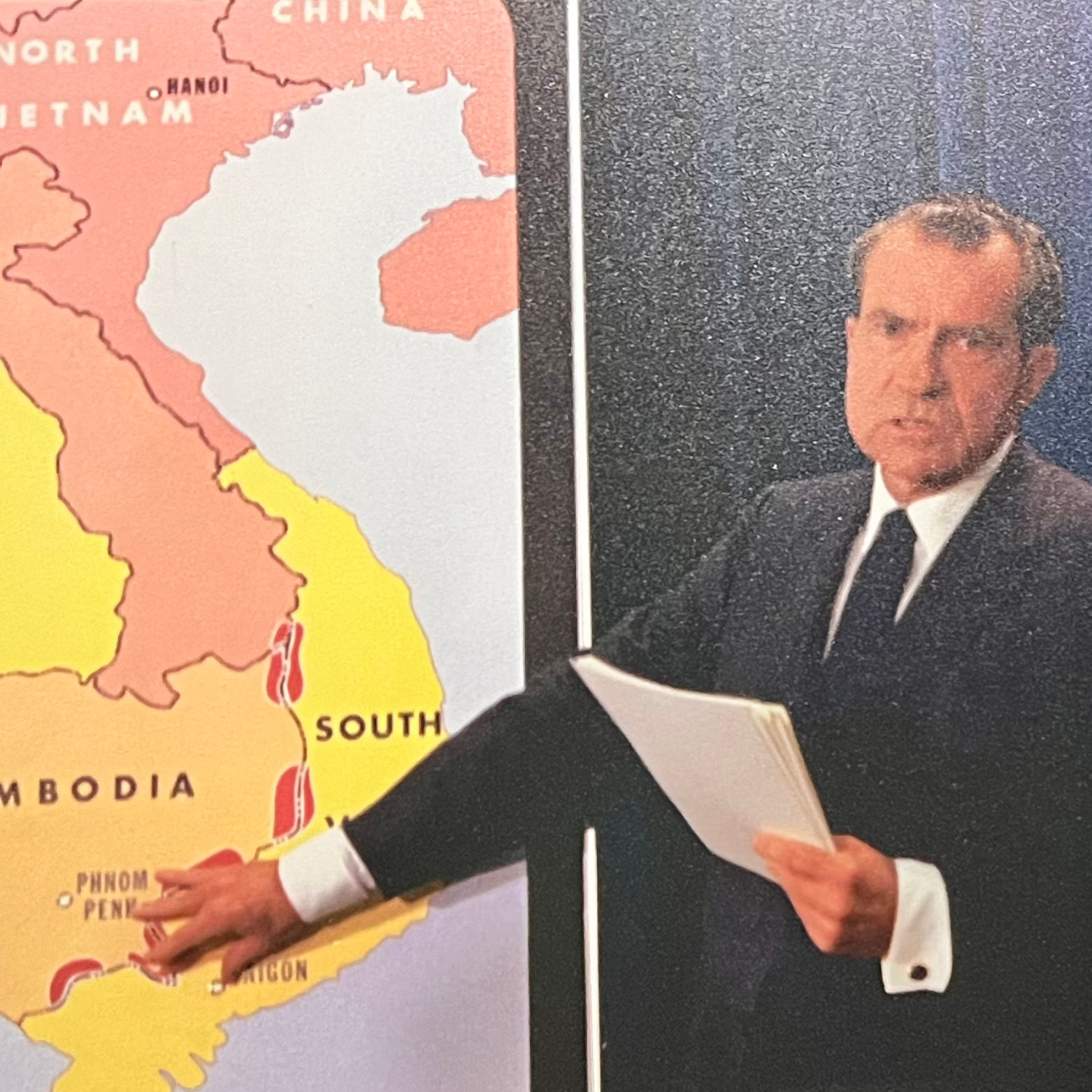

- President Nixon uses maps and charts to support his televised address on American involvement in Vietnam

I promised to end this war. I shall keep that promise. - April 30, 1970

I promised to win a just peace. I shall keep that promise. - April 30, 1970

- American soldiers on tanks in Cambodia - May 1970

Our ... choice is to go to the heart of the trouble. That means cleaning out major North Vietnamese and Viet Cong occupied territories - these sanctuaries which serve as bases for attacks on both Cambodia and American and South Vietnamese forces in South Vietnam ... - 1970

Destroy North Vietnam's war-making ability by sending American forces to join South Vietnamese troops in attacking supply routes in Laos and Cambodia - known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail - to break the Communist strongholds both through ground incursions and escalating the air war.

This is not an invasion of Cambodia... Once enemy forces are driven out of these sanctuaries and once their military supplies are destroyed, we will withdraw. - 1970

His announcement 10 days later that he was sending U.S. ground forces into Cambodia to clean out communist sanctuaries shocked many and spurred a fresh round of protests.

On May 1, the protests at Kent State University in Ohio began peacefully, but that night they turned to violent clashes between protesters and police. Fearing escalation, the mayor of Kent declared a state of emergency and asked Ohio's governor to dispatch the Ohio National Guard. The next day, confrontations continued with arson and sabotage, tear gas, and arrests.

Another rally was called for Monday, May 4. An order to disperse was issued; the protesters, ignoring it, began throwing rocks at the Guardsmen.

In a moment that has crystallized in the national memory but has never been fully explained, some of the Guardsmen pointed their guns toward the crowd and fired. Four students were killed, and nine were injured. This tragic event fueled the sense of outrage over the Government's Vietnam policy.

| 1971: | |

|---|---|

| Nixon's announcement of a planned visit to China furthers one of its goals - unsettling the North Vietnamese, who suspect Nixon will attempt to undermine Chinese support of the communist forces in Vietnam. | |

| January 1971: | President Nixon reduces American troops in Vietnam to 280,000: a nearly 50 percent cut from when he took office. |

| February 1971: | Operation Lam Son 719, an attack by South Vietnamese troops with U.S. support on communist forces in Laos, is repulsed by the North Vietnamese. |

| May 1971: | In secret negotiations, Kissinger offers a plan to North Vietnam consisting of a ceasefire, unilateral American withdrawal, and return of the prisoners of war. But Hanoi continues to demand the overthrow of the Saigon government. |

| June 1971: | The New York Times becomes the first of several major newspapers to publish excerpts from the Pentagon Papers, including classified secret documents that revealed misleading statements made to the American people by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations about the Vietnam War. |

| VIETNAM WAR | |

- February 7, 1971 - American soldiers support the South Vietnamese invasion of Laos known as Lam Son 719

By the Spring of 1971, a collection of anti-war groups decided to produce the largest demonstration yet and bring attention to their cause by shutting down the United States Government. On May 1. 1971, they blockaded bridges leading into Washington and obstructed major roads inside the capital city.

Unwilling to let the May Day protesters continue, the police made mass arrests of more than 7,000 protesters - sweeping people up in vans, and holding them in a makeshift detention center at a stadium on the outskirts of town. Although the city continued to function without disruption, some objected to the arrests, calling them examples of martial law.

The aim of May Day actions is to raise the social cost of the war to a level unacceptable to America's rulers.

- May Day Tribe protest group's tactical manual, 1971

| 1972: | |

|---|---|

| Nixon's landslide reelection in November 1972 was due in part to the nation's approval of his progress toward keeping his promise of achieving an honorable peace: a half million troops withdrawn, the draft ended, and peace negotiations showing promise. | |

| January 1972: | Nixon has reduced American troops in Vietnam by nearly 400,000 to 133,000. |

| February 1972: | Nixon makes his historic visit to China. |

| March - April 1972: | North Vietnamese troops make significant and startling advances, crossing the demilitarized zone and attacking the cities of Quang Tri and Hue in South Vietnam - an action that became known as the Easter Offensive. |

| May 1972: | Nixon is welcomed to Moscow during a visit to the Soviet Union, an ally of North Vietnam, which is being bombed by U.S. forces. |

| October 1972: | A draft peace treaty is worked out with North Vietnam in Paris, and Kissinger announces: "Peace is at hand." |

| November - December 1972: | The Paris peace talks falter over last-minute changes to the agreement. On December 14, Le Duc Tho leaves Paris and the peace talks come to a halt. |

| December 18, 1972: | In an effort to restart the talks, President Nixon orders a controversial campaign of 12 days of heavy bombing in North Vietnam that drops more than 20,000 tons of bombs on Hanoi and Haiphong in North Vietnam. Officially designated Linebacker II, this became known as the Christmas Bombing. |

| VIETNAM WAR | |

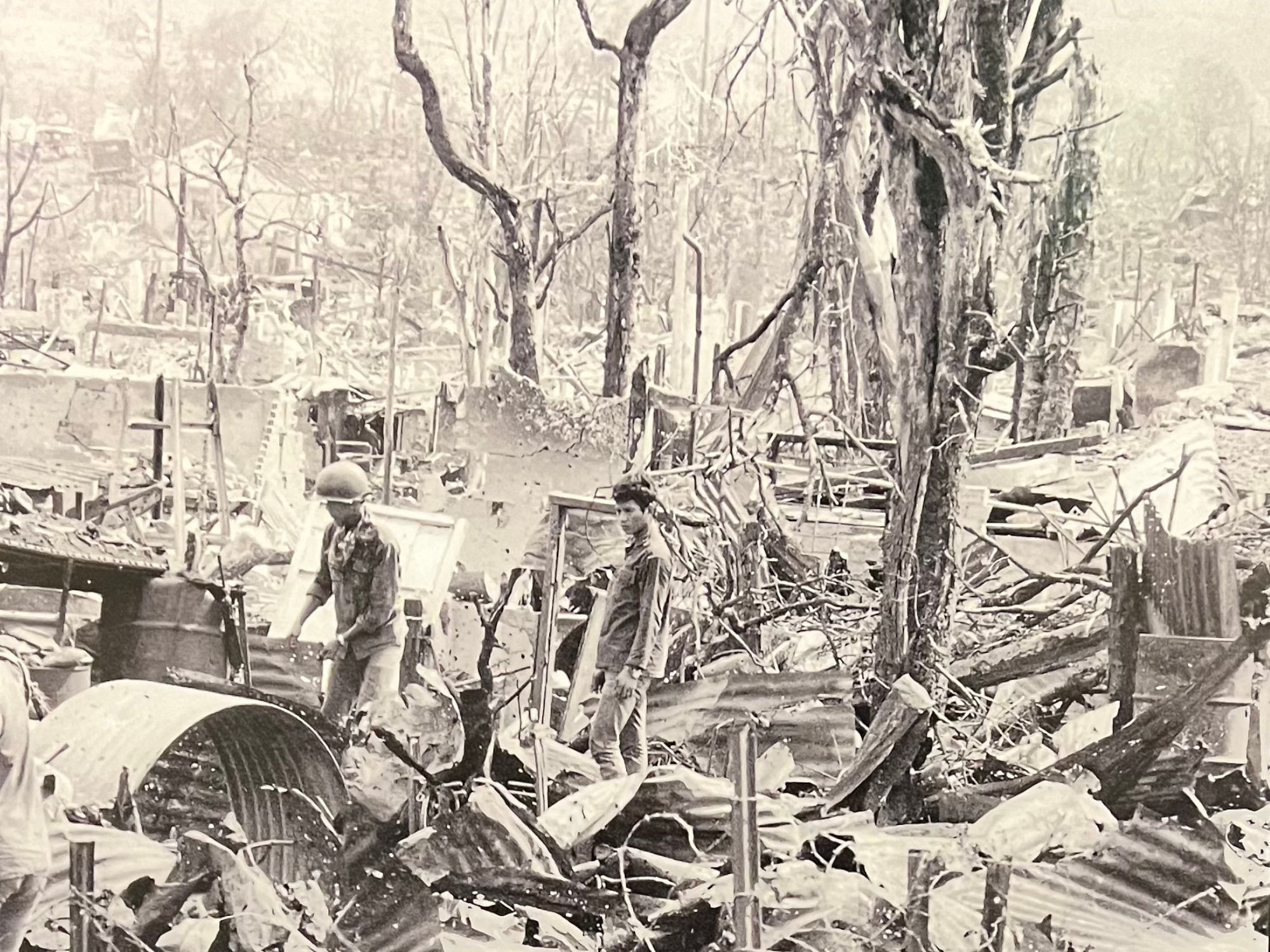

- South Vietnamese soldiers and citizens move through the rubble after the Easter Offensive

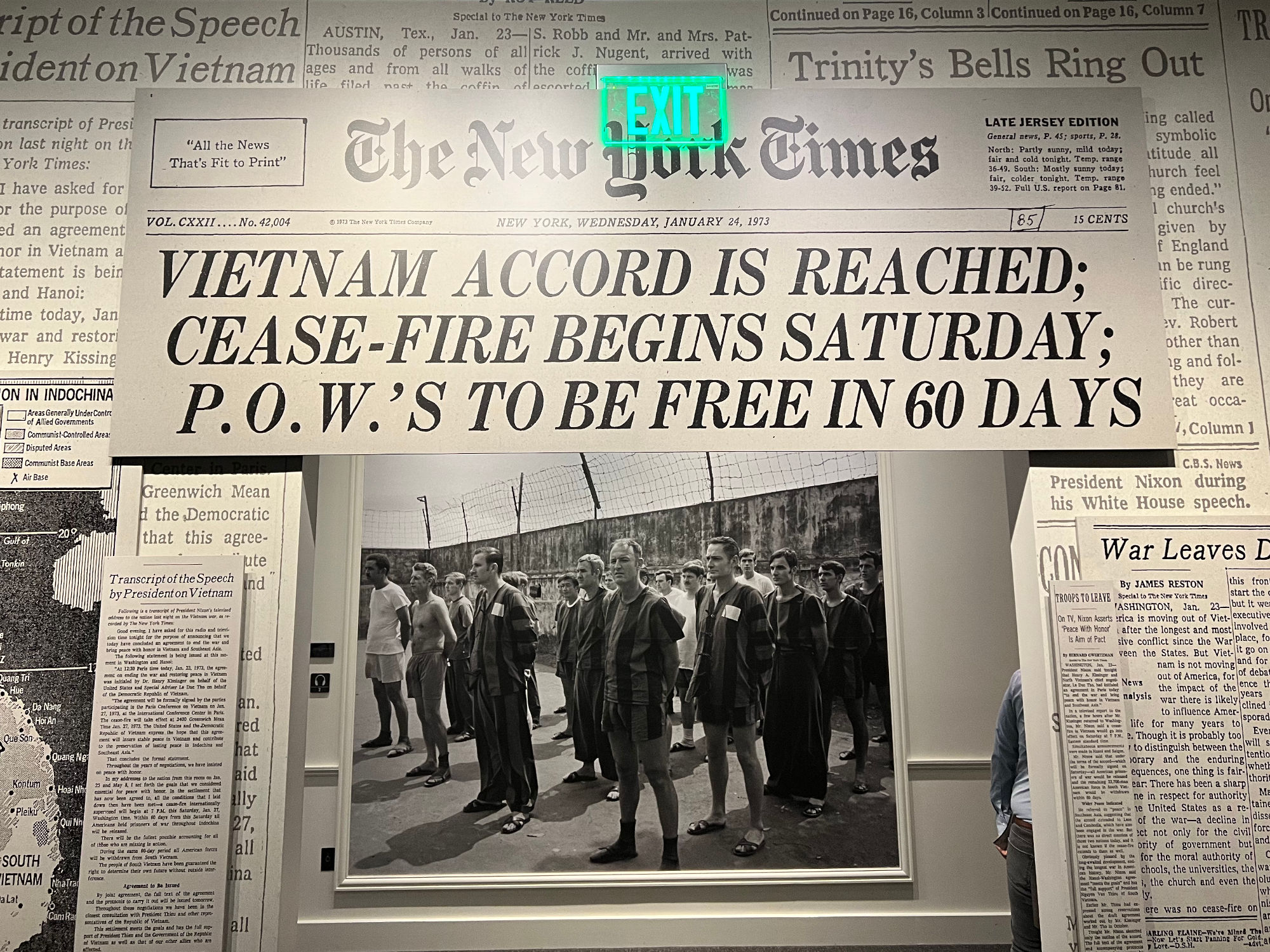

| 1973: | |

|---|---|

At the official end of the war

| |

| January 8, 1973: | Paris peace talks resume. |

| January 23, 1973: | In a nationally televised Oval Office address, President Nixon announces the peace agreement, ending America's involvement in Vietnam and securing the return of all American prisoners of war. |

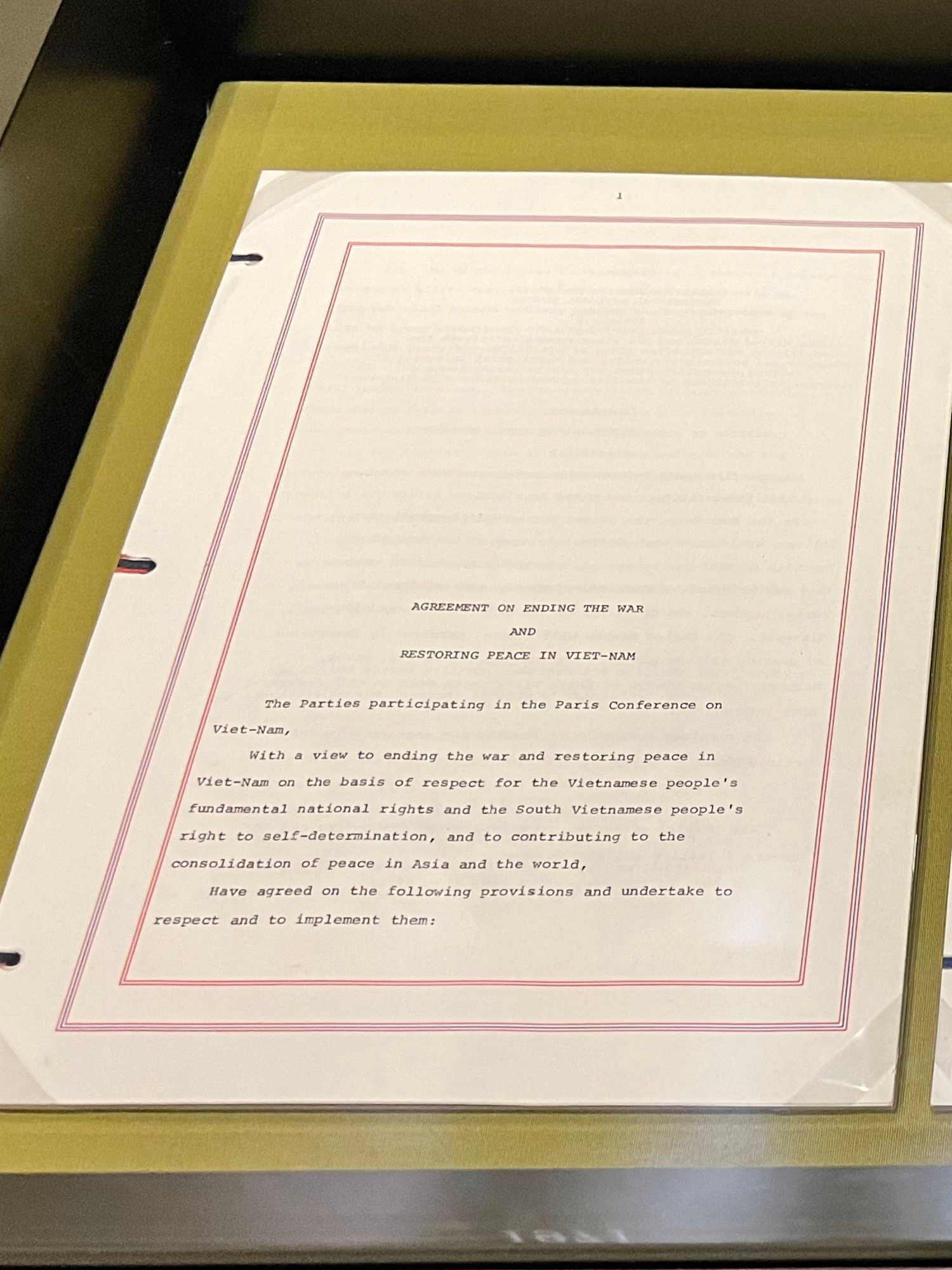

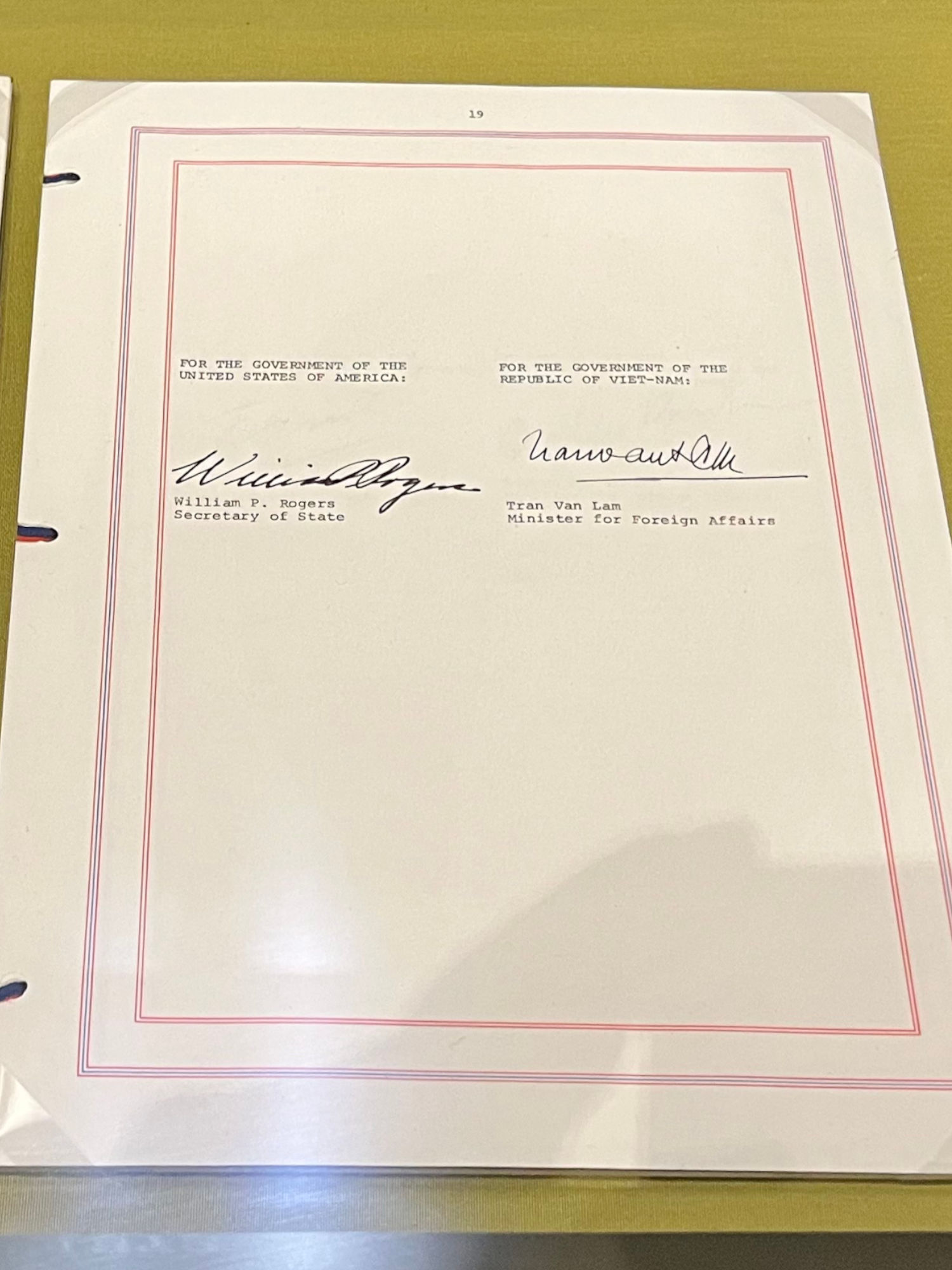

| January 27, 1973: | The Paris Peace Accords are signed. Following the removal of the remaining American troops and return of prisoners, North and South Vietnam will reach a political settlement. The United States will provide economic aid for rebuilding North and South Vietnam and continue providing military aid to South Vietnam. |

| March 1973: | The last American combat troops leave Vietnam. |

| VIETNAM WAR | |

- January 22, 1973 - The US, and North Vietnamese delegations meet to finalize the terms of the Paris Peace Accords

- Marking the end of the Vietnam War: the Paris Peace Accords (facsimile)

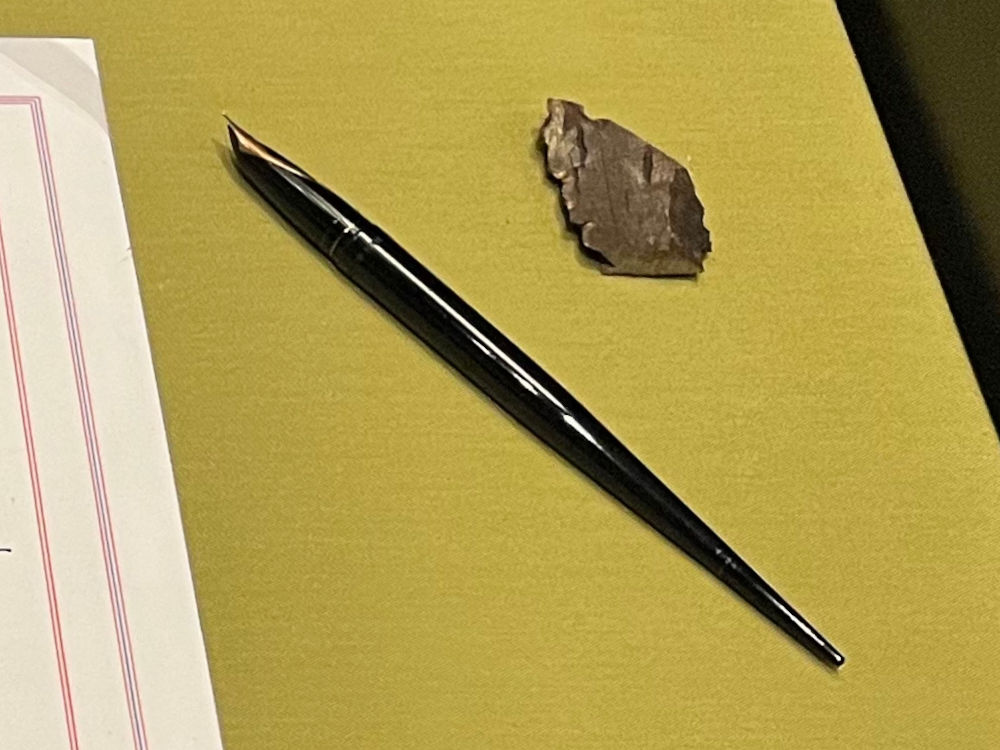

- The first pen used by Secretary of State William Rogers to sign the agreement

- A bomb fragment from the December 1972 bombing recovered by a POW from his cell in Hanoi

The cease-fire would go into effect at midnight on January 27.

Colonel William Nolde was killed in Vietnam just 11 hours before that cease-fire began.

He was a decorated officer who had served in the Army in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars and the final soldier killed in the war.

The final casualties from the other branches of the service were:

- U.S. Air Force

TSgt James D. Farmer

August 13, 1934 - January 16, 1973

- U.S. Marine Corps

PFC Mark J. Miller

April 1, 1952 - January 26, 1973

- U.S. Navy

CDR Harley H. Hall

December 23, 1937 - January 27, 1973

- Lt. Col. William B. Nolde (1929-1973) was the last American soldier killed in Vietnam before the cease-fire of the Paris Peace Accords

I never hated the war in Vietnam more than I did at that moment."- From in the Arena, About meeting with the family of Col. William Nolde

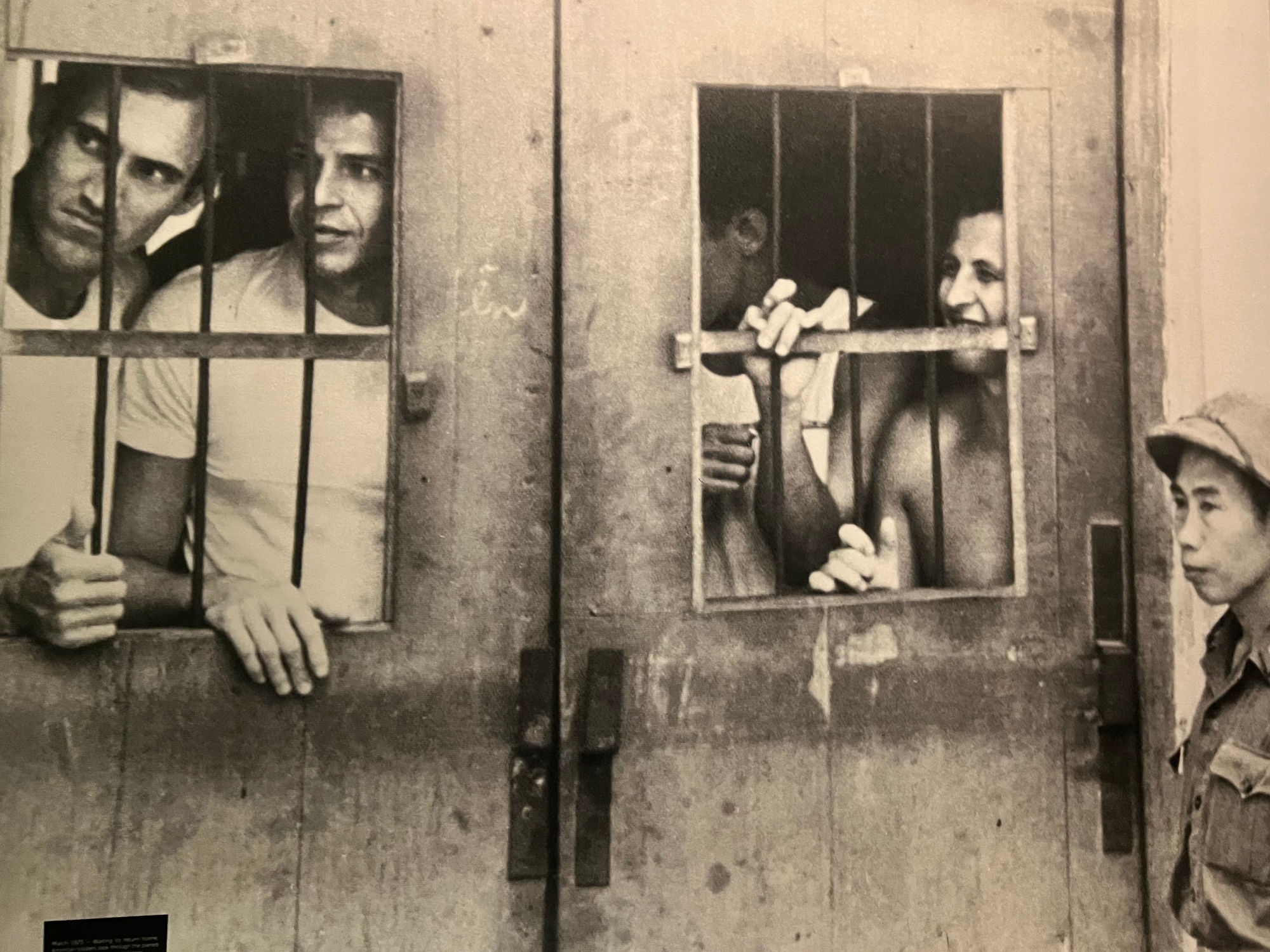

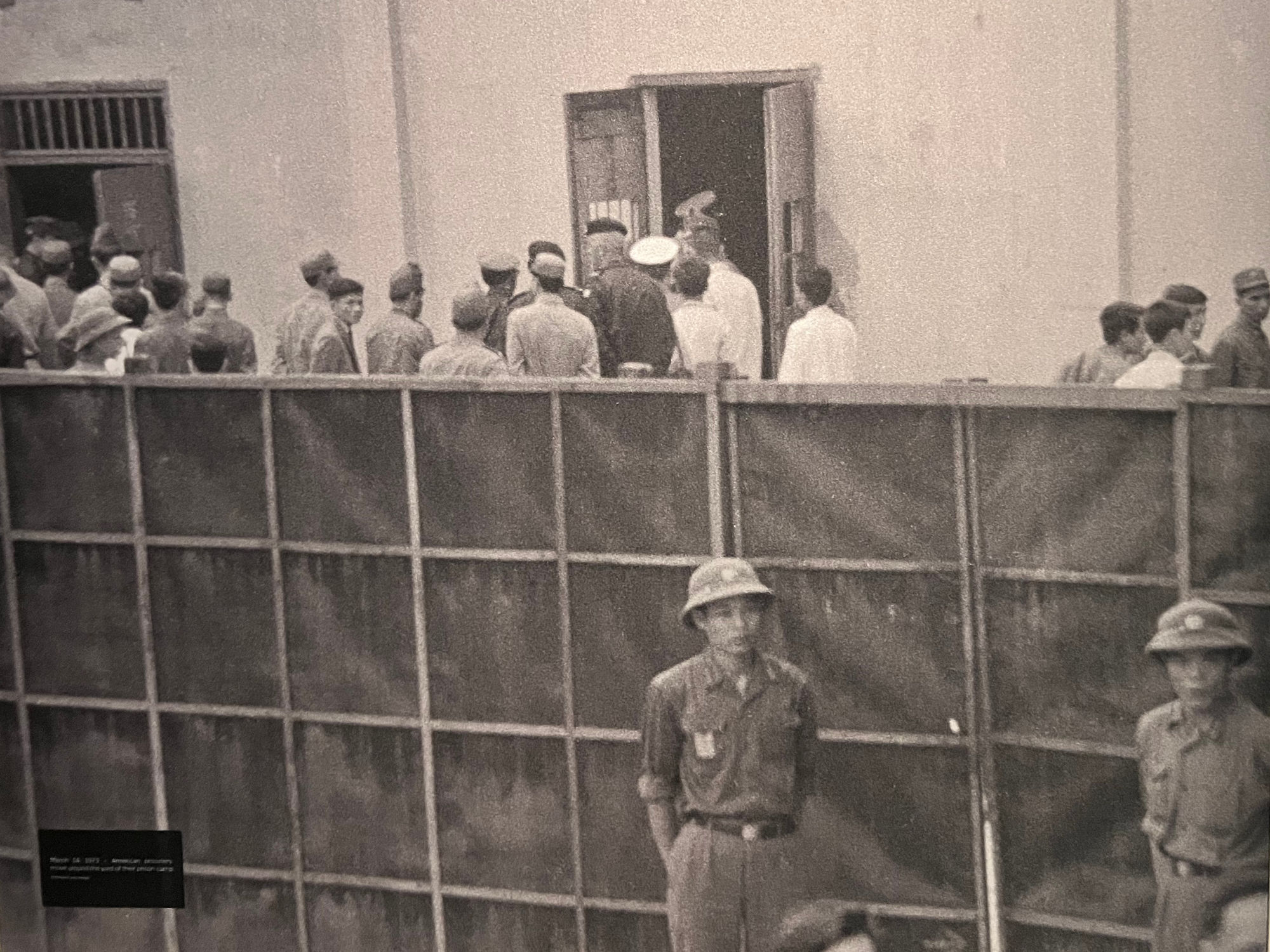

Our POWs had been courageous in action; they were even more courageous in captivity.

North Vietnam refused to follow the Geneva Conventions in its treatment of American POWs, claiming they were instead "war criminals" for their participation in a war of aggression by the United States. This, they maintained, gave them the right to subject the POWs to brutal, barbaric treatment. (Similarly, South Vietnam at times subjected captured North Vietnamese and members of the Viet Cong to brutal treatment as criminals.)

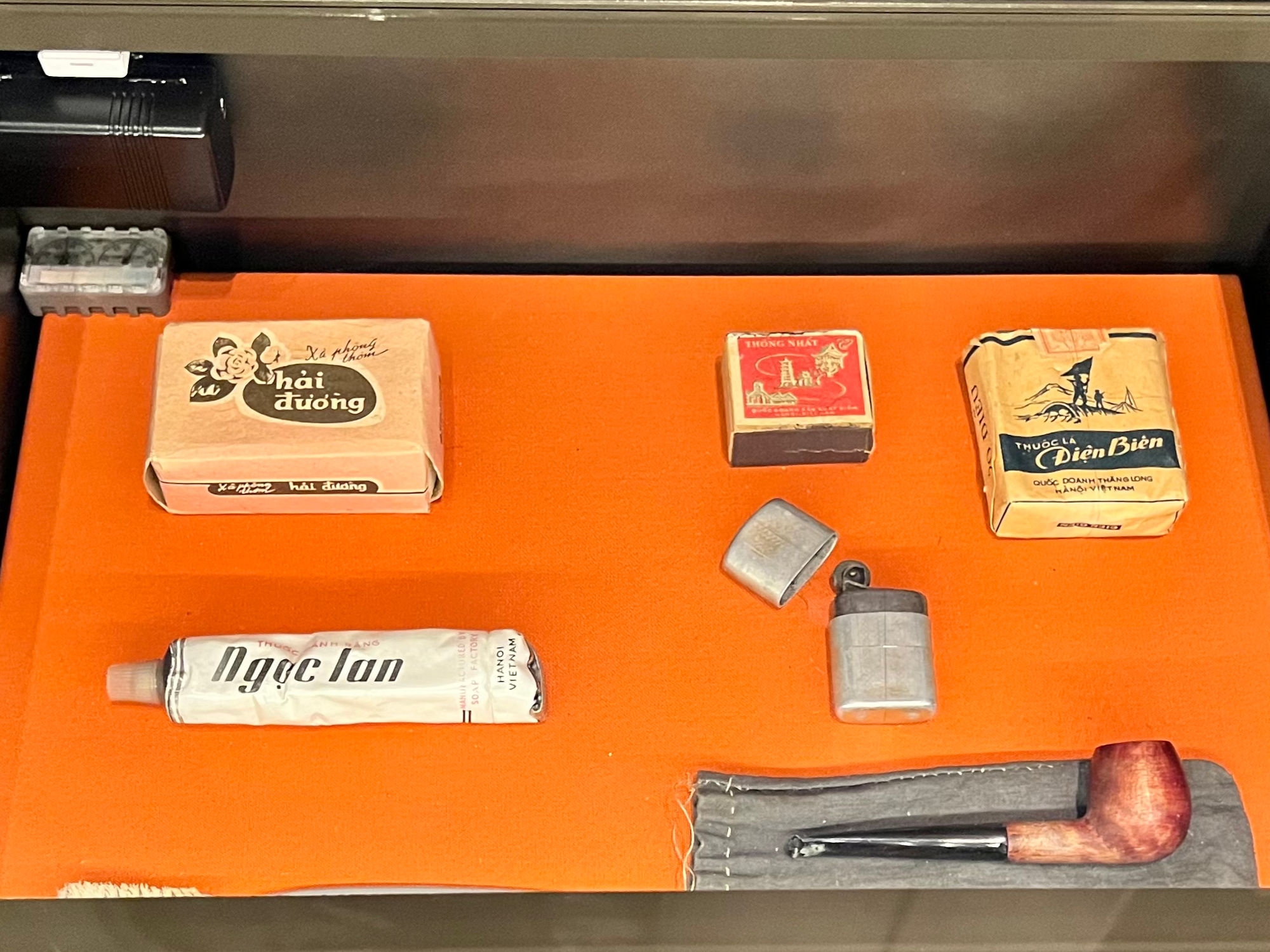

- Soap

- Matches

- Cigarettes

- Toothpaste

- Lighter

- Toothbrush

- Pipe and bag

The lighter that belonged to a North Vietnamese guard, the bag for a pipe made out of fabric from pajamas, and other small items of daily life were brought back by Vietnam POWs.

Among those on that first flight home was Navy Cmdr. Everett Alvarez Jr., the first American pilot to be shot down over North Vietnam. Commander Alvarez spent 8 and a half years in captivity, making him the 2nd longest-held POW when the war ended.

When the POWs returned home, they brought harrowing stories of their treatment in North Vietnam's POW camps. They were regularly subjected to torture, solitary confinement, and deprivation of food, medical treatment, and sanitary facilities.

Starting in 1969, President Nixon put increasing public and political pressure on the North Vietnamese to treat the POWs in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Later that year, North Vietnam issued an internal resolution to change its treatment of American prisoners accordingly.

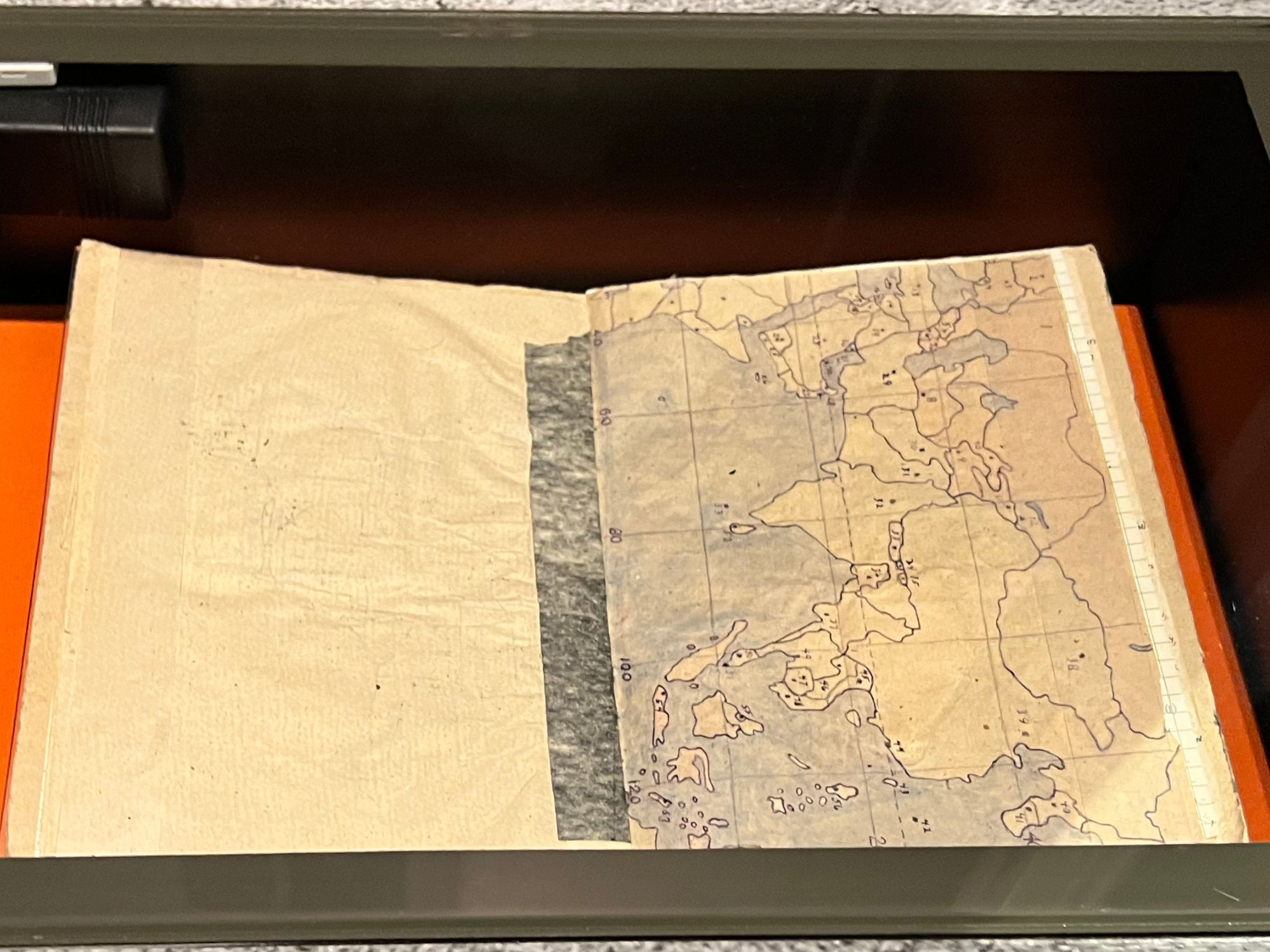

- Over the nearly 10 years of his captivity, this POW filled his journal with hand-drawn maps and lists of words, places, names of sports teams, items of clothing, and more.

- These POW bracelets were sold in the United States to commemorate soldiers captured or missing in action.

- President Nixon receives the flag embroidered on a handkerchief by former POW Lt. Col. John Dramesi during his captivity in North Vietnam.

American flag made out of fabric remnants by Col. John A. Dramesi and other captive POWs during his six years as a POW in Hanoi. It was presented to the President by Col. Dramesi and displayed at the White House Prisoner of War dinner on May 24, 1973.

- Soldiers prepare to depart Vietnam on March 29, 1973

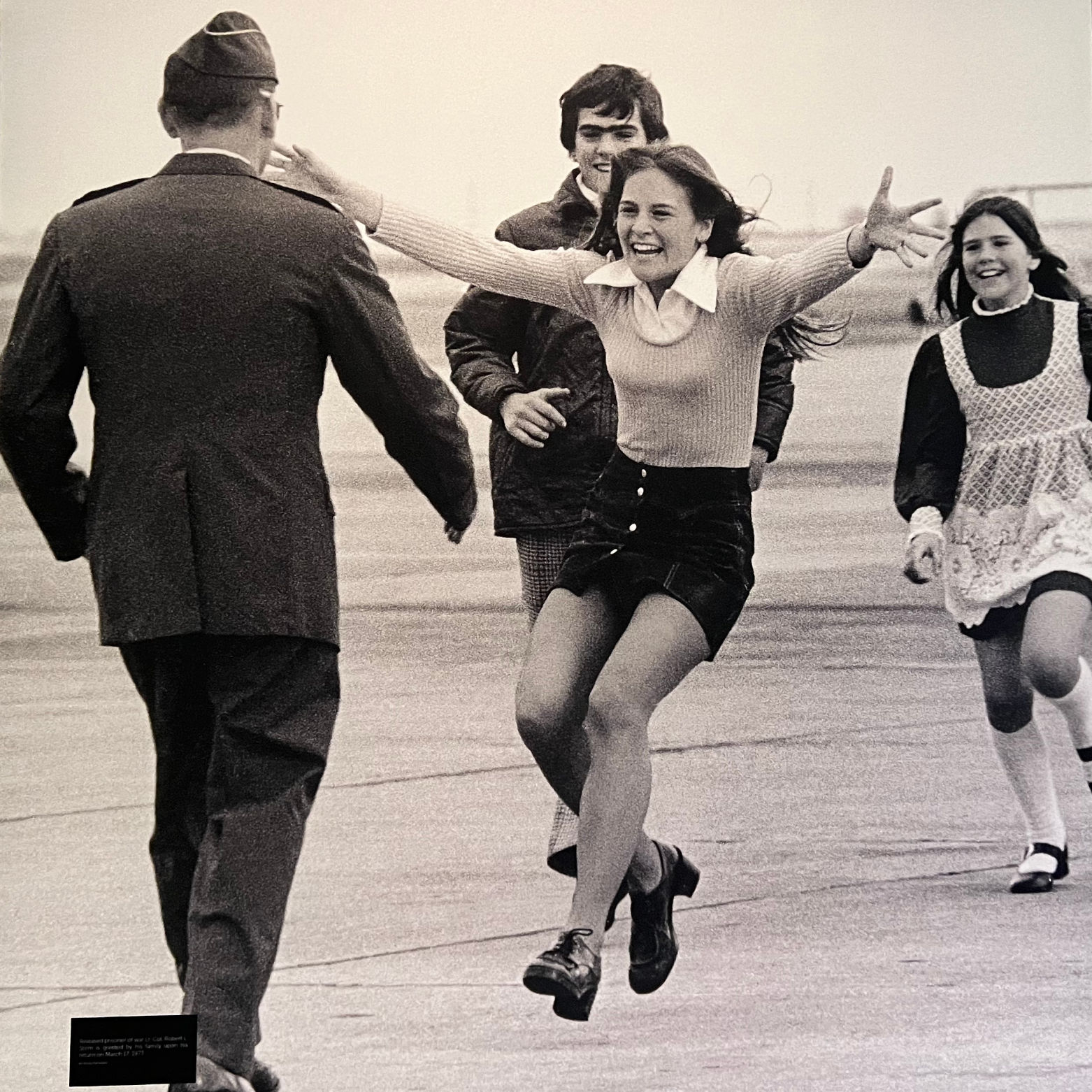

- Released prisoner of war Lt. Col. Robert L. Stirm is greeted by his family upon his return on March 17, 1973

Some protesters, who had clamored for the troops' return, now gathered at the airports to meet the soldiers with angry slogans. Service members were even encouraged to change out of their uniforms before they landed to avoid being confronted by the protesters. Once at home, they faced a new set of challenges simply in trying to reintegrate into their former lives - struggling to find a job and get necessary medical and psychological treatment.

Almost as bad as the abuse by the few was the indifference of the many. War-weary civilians didn't want to talk about Vietnam anymore; they wanted it to disappear, and the returning troops were a painful reminder of what President Nixon in his 1971 State of the Union had called "a long, dark night of the American spirit."

By 1974, North Vietnam had reignited the fighting in the South. In Washington, Congress dramatically reduced the President's request for funds to aid South Vietnam, and a combination of economic and political factors precluded further military aid. The South Vietnamese were unable to hold off the renewed communist offensive. In April 1975, nine months after President Nixon's resignation, South Vietnam's capital Saigon fell, ending the war with North Vietnam's victory.

The war left indelible scars on the American psyche and reputation as well as lingering wounds on the landscape, infrastructure, and people of Vietnam. Some two million Vietnamese - soldiers and civilians - had died in the war. As many as four million were wounded, and more than a million fled as refugees after the Communist victory.

- That the U.S. not abandon, or worse overthrow, its ally South Vietnam - an action that would have a lasting effect on America's global standing and reputation

- That the POWs be returned

Others had differing definitions for what constituted an honorable end - from immediate withdrawal to military defeat of North Vietnam. Some felt that Nixon's claim that his way was "peace with honor" painted those with different opinions and goals as dishonorable. Others felt that Nixon did not truly believe the agreement would hold, while still others held that Congress undercut any chance of success by cuts in funds to aid South Vietnam.

The cuts in aid funding to Vietnam after the war by Congress certainly affected the ability of the South Vietnamese to survive, contributing to their defeat in 1975. This conclusion to the war complicates the issue of the peace achieved by Nixon, and historians, scholars, and interested citizens continue to debate Nixon's record on the Vietnam War.