Early in the morning of June 17, 1972, five men were arrested with electronic surveillance equipment inside the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C. Two years later, President Nixon became the first American President to resign.

Why? What happened?

A generation ago, the public witnessed the long, often confusing, unraveling of revelations about illegal wiretapping, break-ins, payoffs, political dirty tricks, and other Governmental abuses of power.

This scandal, which began with what the Nixon White House termed a third-rate burglary, ultimately led to a Constitutional crisis.

2600 Virginia Avenue, NW, Washington D.C.

https://www.google.com/maps/place/The+Watergate+Hotel

Believing that he faced a conspiracy of former Kennedy and Johnson officials who would continue leaking classified documents to destroy his Vietnam policy, President Nixon instructed his aides to form a special unit both to look for the group behind this national security leak and to discredit his perceived political enemies.

- Later known as "the Plumbers," the Special Investigations Unit acted outside of the FBI and the CIA.

Even after former Pentagon official Daniel Ellsberg made a public confession on June 28, 1971, President Nixon continued to press for action against a suspected anti-Nixon conspiracy. These Presidential orders led to illegal actions and abuses of governmental power.

| THE PLUMBERS: | |

|---|---|

| The Special Investigations Unit Popularly known as the Plumbers - operated from July to December 1971. Besides Ellsberg, the Plumbers investigated unauthorized leaks of classified materials on U.S. - Soviet arms control talks and the Indo-Pakistani War. At the President's request, the unit provided Charles Colson with information to discredit political adversaries and to deflect public attention from the administration's handling of the Vietnam War. Colson leaked confidential FBI information on Ellsberg and arranged for a forged government document to be given to Life magazine. Designed by Plumber E. Howard Hunt the forgery was part of an initiative ordered by President Nixon to discredit Democrats by implicating the late President John F. Kennedy in the 1963 assassination of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem. | |

| Egil "Bud" Krogh As co-director of the Special Investigations Unit, Krogh believed that protecting national security secrets justified domestic covert action even if it violated the law. In 1973, he pled guilty to depriving Dr. Lewis Fielding of his civil rights and served six months in prison. "I came to accept that I could no longer defend my conduct" he later wrote "If I continued to justity violating rights I continued to enjoy, I would be ... a traitor to the fundamental American idea of the right of an individual to be free from unwanted government intrusion in his life." |

| David Young Former assistant to Henry Kissinger, young was co-director of the Special investigations Unit. He placed a sign saying "Plumbers" outside their office. He received immunity from prosecution in exchange for his cooperation with Federal authorities. |

| G. Gordon Liddy Liddy was an attorney and former congressional candidate who had served five years with the FBl. Bud Krogh recruited him from the Treasury Department in mid 1971 for the Plumbers unit. Liddy, who refused to cooperate with investigators, received the longest sentence of any of the Watergate conspiraters. He was paroled in September 1977 after serving four and a half years in prison. |

| E. Howard Hunt Hunt joined the CIA after World War II. Hunt worked with Cuban exiles during the planning of the failed Bay of Pigs operation in 1961. Charles Colson recommended Hunt to President Nixon in 1971 for the Plumbers. From July 1971, Hunt worked on projects for Colson and recruited Cuban Americans for secret operations. Hunt served 33 months in prison for his role in the Watergate break-in. |

| Bernard L. Barker Born in Cuba, Barker worked with Hunt in the ClA's failed Bay of Pigs operation. When recruited by Hunt for the Plumbers in 1971, he ran a real estate office in Miami that the Cuban American team would later use as an operational headquarters. He was arrested on June 17 1972, in the Watergate break-in. |

| Eugenio Rolando Martinez Born in Cuba and nicknamed "Musculito," Marine Participated in the CIA's 1961 Bay of Pigs operation. Hunt recruited him in Mimi in 1971 for Liddy's operational team. He was arrested on June 17, 1972, in the Watergate affair. According to the Senate Watergate report, Martinez remained a CIA operative until his arrest. |

| WATERGATE | |

- Warrantless Wiretaps

May 1969 - February 1971

The White House initiated FBI wiretaps without a court order on three journalists and 14 individuals on the National Security Council (NSC) staff, in the State Department, in the Defense Department, and on the White House staff. In 1969 the White House also arranged its own wiretap on a journalist, Joseph Kraft. Some, but apparently not all, of these wiretaps reflected concerns over national security leaks, especially from opponents of the Administration's Vietnam policy.At the time, wiretaps without a court order were legal only if placed for national security reasons. A Senate investigation later determined, however, that two of the wiretapped White House staffers were domestic advisers who did not have access to classified materials; and, in at least one case, the wiretaps on the NSC staff continued long after the individual had left government service.

The White House had all of these wiretaps removed by early 1971. In June 1972, in a separate case, the Supreme Court ruled that warrantless national security wiretaps - those without a Court's permission - violated the U.S. Constitution.

- The Huston Plan

July 1970

In the wake of widespread campus protests over U.S. military intervention into neutral Cambodia in April 1970 and a spike in domestic bomb threats reported by the FBI, President Nixon sought to increase domestic intelligence gathering. In July 1970, he briefly authorized new powers to permit the intelligence community to conduct more domestic spying without a court order. Confronted by the immediate opposition of Attorney General John Mitchell and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, the President rescinded this program a week later. This set of new powers was known as the "Huston Plan" after Tom Charles Huston, the White House aide who coordinated the effort.This incident undermined the President's confidence that the FBI would do what was necessary against those he considered radical opponents of the war.

| PRIMARY PARTICIPANTS: | |

|---|---|

| Daniel Ellsberg | Briefly served as a Pentagon analyst in the Johnson administration, came to oppose the Vietnam War. In an effort to influence congressional and public opinion, he leaked a highly classified Department of Defense study, which became popularly known as the Pentagon Papers, to certain members of Congress and to the New York Times. Leaking classified material is illegal and Ellsberg was later indicted for violating the Espionage Act. |

| Charles Colson | Charles Wendell "Chuck" Colson served as special counsel to President Nixon from 1969 to 1975. Colson assisted the President in building a new political coalition and also supervised operations to damage the President's opponents. After the Watergate arrests, the President and Colson worried what the scandal might reveal about Colson's activities. Colson plead guilty to intentionally leaking information to discredit Daniel Ellsberg and served seven months in jail. |

| John D. Ehrlichman | Joined the White House staff in January 1969. A Seattle attorney, Ehrichman first worked for Richard Nixon as an advance man in the 1960 Presidential campaign. In response to the President's demand to stop leaks of classified material, Ehrlichman formed the Plumbers in July 1971. |

| WATERGATE | |

- The New York Times begins publishing the Pentagon Papers

June 13, 1971

The New York Times published the first in a series of excerpts from the Pentagon Papers. The Nixon administration went to court in an effort to halt further publication. The Supreme Court, however, ruled that the federal government had no legal authority to prevent publication in advance.- The Pentagon Papers

Completed in 1969, the 47-volume Pentagon Papers was a study prepared at the request of President Kennedy's and President Johnson's Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara. Written to recount and analyze America's involvement from 1945 through 1967, this top-secret document was designed to provide a comprehensive history to future policymakers who might be confronted with similar foreign policy challenges.

- The Pentagon Papers

- Investigating Civil Servants

July 2, 1971

In the tense weeks after the Pentagon Papers leak, President Nixon also sought action against perceived political opponents within the Federal Government. Convinced that some civil servants were intentionally misrepresenting monthly unemployment figures, President Nixon ordered an Investigation into the loyalty of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The President asked specifically how many people in the unit were Jewish Americans. In late July, White House staffer Frederic V. Malek reported that there were 19 in the Bureau. Civil service protections prevented any from being fired. Discrimination on the basis of religious affiliation is illegal. This form of abuse of Governmental power would later be cited in the Articles of Impeachment against President Nixon. - Firebombing the Brookings Institution

Believing that the conspiracy extended into the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank, President Nixon repeatedly ordered the seizure of any classified materials held there. Charles Colson, who was given responsibility with Ehrlichman for the seizure, suggested that Brookings could be firebombed to distract security while the secret papers were recovered. When John W. Dean III alerted Ehrlichman to Colson's arson plan, it was abandoned. - Fielding Break-in

September 3, 1971

After the Plumbers reported that Daniel Ellsberg's former psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Fielding, had refused to hand over his confidential notes to the FBI, John Ehrlichman authorized a "covert operation to examine all the medical files still held by Ellsberg's psychoanalyst..."Planned by Liddy and Hunt and funded with the help of Charles Colson, the break-in at Dr. Fielding's office in Beverly Hills, CA occurred on the night of September 3. 1971. The burglars - Bernard Barker, Rolando Martinez, and Filipe DeDiego - turned the office upside down but found nothing. Before leaving the crime scene, they threw prescription drugs on the floor to mislead police into thinking that an addict had committed the crime. On September 8, Ehrlichman reported to the President that the Plumbers had undertaken a "little operation' in Los Angeles that had gone wrong, "which, I think it's better that you don't know about."

- Obtaining Medical Records

In August 1971, John Ehrlichman initiated his approval of Krogh and Young's proposal to covertly obtain Ellsberg's medical records. - Enemies List

June 1971

As President Nixon assessed the damage to his Presidency from the Pentagon Papers leak, he ordered Haldeman on June 23, 1971 to have the Internal Revenue Service undertake special audits of his political opponents and suggested that Charles Colson create a list of "the ones we want." John Dean was assigned the "Political Enemies Project" to coordinate action on the list. After consulting with Colson, Dean presented a list of 16 names to Haldeman's staff on September 14. The President learned about the list and assented to its use with the IRS on September 18.The September 1971 list included conductor Leonard Barnstein, computer pioneer Thomas J Watson Jr., former Defense Secretary Clark M. Clifford, and journalists Mary McGrory and Daniel Schorr.

- Daniel Schorr's Story

In August 1971, the White House sought derogatory information from the FBI on CBS news correspondent Daniel Schorr. Misunderstanding the request the FBI interviewed Schorr as if the journalist was under consideration for a federal appointment. Alter Schorr complained about the FBI investigation, the White House had it stopped. In September 1971 Haldeman reported to the President that Schorr was on the list for harassment by the IRS. The House Judiciary Committee cited this misuse of the FBI in its second article of impeachment in July 1974.

- Daniel Schorr's Story

This is a Conspiracy. - President Nixon to H.R. Haldeman, July 1, 1971

President Nixon set the stage for the activities that would lead to the Watergate scandal by demanding more inside information on political rivals and supporting covert activities to disrupt other campaigns.

With the knowledge of the President, White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman initiated both political intelligence and "dirty tricks" operations for the 1972 campaign. In the spring of 1971, Haldeman's staff recruited Donald Segretti to do dirty tricks. Later that year, Haldeman worked with Attorney General John Mitchell to set up a political intelligence unit, led by former Plumber G. Gordon Liddy, inside the Committee for the Re-election of the President.

| PRIMARY PARTICIPANTS: | |

|---|---|

| John N. Mitchell | Richard Nixon's law partner before becoming the candidate's 1968 campaign manager. Mitchell held office as Attorney General of the United States from 1969 until he left on February 15, 1972, to run the President's re-election campaign. Mitchell served 19 months in prison for his role in the Watergate cover-up. |

| Jeb Stuart Magruder | An executive in the cosmetics industry before joining the White House Office of Communications in the summer of 1969. In 1971, Magruder became deputy director of the President's re-election committee. In 1973, he pled guilty to conspiracy to unlawfully intercept wire and oral communications, to obstruct justice and to defraud the United States and served seven months in prison. |

| Chapman, Strachan, and Segretti | White House staffers Dwight Chapin and Gordon Strachan had attended the University of Southern California with Donald Segretti, Chapin contacted Segretti in April 1971 about a possible White House Job. Strachan and Chapin then hired him in June 1971. Chapin remained Segretti's main contact until Segretti and his group were absorbed into G. Gordon Liddy's intelligence program in February 1972. Lidays Intelligence program in February 1972 |

| WATERGATE | |

- The President Requests Better Political Intelligence

April 19, 1971

At a meeting with Attorney General Mitchell the President asks for better intelligence on his political rivals. - The White House Orders Dirty Tricks

Early 1971

Haldeman informed the President in May 1971 that planning for a dirty tricks operation was underway. The President's appointments secretary Dwight Chapin and Haldeman's assistant, Gordon Strachan, hired Donald Segretti. Segretti recruited 22 operatives and received $45,000 from President Nixon's personal lawyer, Herbert Kalmbach. Segrettis group organized hecklers to disrupt opposition rallies, forged letters on Democratic campaign stationery to divide the Democrats, and infiltrated spies to collect political intelligence. In addition, President Nixon instructed Colson in December 1971 to create a false write-in campaign for Senator Edward M. Kennedy in the New Hampshire primary to siphon votes from then front-runner Senator Edmund S. Muskie of Maine. - The President Orders Surveillance of Senator Edward Kennedy

June 23, 1971

At a meeting with Haldeman, the President requested increased intelligence gathering on Senator Kennedy to "get him in a compromising situation*" On July 1, Haldernan informed the President that his lawyer, Herbert Kalmbach, would pay for this out of a special campaign fund. Although the White House would drop this idea later in the summer, discussion over improving political intelligence continued. - Creating a Spy Unit

November 4, 1971

Alter months of considering the need for more political intelligence, Mitchell and Haldeman decided to create a special espionage unit in the re-election committee and discussed recruiting G. Gordon Liddy to run it. Bud Krogh had earlier told John Dean and John Ehrlichman that Liddy was the man for the job. - Liddy and Hunt Start Planning

December 1971

After joining the re-election committee in December, Liddy worked with former Plumber colleague E. Howard Hunt - who was still a paid consultant to Charles Colson - to prepare an intelligence plan. Attorney General Mitchell, who was about to leave the Justice Department to run the President's campaign was responsible for approving the plan.- Mitchell, Colson, & GEMSTONE

January 27, February 4, & March 30, 1972

G. Gordon Liddy proposed GEMSTONE to Attorney General Mitchell twice without success in January and February. After Liddy's second effort, he and Hunt enlisted Special Counsel to the President Charles Colson's help. Colson called Deputy Campaign Director Jeb Stuart Magruder to tell him that Mitchell needed to make up his mind. On March 30, Mitchell considered the plan a third time at a meeting in Key Biscayne, Florida with his close aide Fred LaRue and Magruder. On April 4, 1972, Magruder relayed to Haldeman that Liddy's operational budget had been approved and that Mitchell would receive the raw intelligence. Meanwhile, Mitchell Informed Maurice Stans, the Committee's finance chair, to release the money that Magruder requested for Liddy.- The Key Biscayne Meeting

Mitchell Magruder and LaRue each gave different accounts of the March 30 meeting:

- Mitchel testified that he threw the paper back at Magruder and said, "Not again."

- Magruder recalled Mitchell agreeing to fund the plan, but reluctantly.

- Le Rue, who did not recall any rejection or approval only heard Mitchell postpone the decision.

- The GEMSTONE Plan

Liddy and Hunt gave the codename GEMSTONE to their proposed one million-dollar-program of counter-demonstrations, Illegal bugging, and surreptitious entries. In early April, Liddy told Hunt that "the Big Man," which Hunt assumed meant Mitchell, had approved a scaled-down version of GEMSTONE. The $250,000 budget included money for break-ins and bugging at the headquarters of the eventual Democratic nominee and of the DNC in Washington, D.C. and at the Democrats' convention hotel in Miami.

- The Key Biscayne Meeting

- Haldeman Learns that Liddy's Plan has been Approved

April 14, 1972

Jeb Stuart Magruder told H.R. Haldeman, through his aide Gordon Strachan, that "2 of 4" of Liddy's operations had been approved. Neither the surviving documentary record, nor the tapes or trial has cleared up the mystery of whether Haldeman knew that these operations involved illegal wiretapping.

- Mitchell, Colson, & GEMSTONE

- The Plan to Break into George McGovern's Headquarters

May 26, 1972

After South Dakota Senator George McGovern won the Democratic primary in Wisconsin and became the likely Democratic nominee, Haldeman ordered Liddy, through Strachan, to focus his intelligence efforts on McGovern. On May 26 and 28, Liddy's group made two unsuccessful attempts to break into McGovern's headquarters in Washington, D.C. Their goal was to plant illegal electronic bugs.

- Charles Colson denied that Hunt or Liddy told him any operational details.

- John Dean, who witnessed Liddy's two presentations to Mitchell, testified that he told Bob Haldeman about the direction Liddy was taking.

- Gordon Strachan, Haldeman's liaison with the re-election committee, destroyed documents after the Watergate arrests, but his surviving notes indicate that Haldeman at least knew about the approval of a Liddy intelligence plan. Strachan told investigators that Haldeman instructed him to have Liddy shift his primary target to Senator George McGovern and that later Magruder told Strachan about one of the attempts to break into McGovern headquarters.

- Bob Haldeman: No evidence has been found to show what, if any, details were shared with Haldeman.

- President Nixon denied knowing anything about GEMSTONE before the Watergate arrests, and investigators found no evidence to contradict his assertion.

| PRIMARY PARTICIPANTS: | |

|---|---|

| John W. Dean III | John Dean became Counsel to the President in July 1970. With the President's approval, Dean was made coordinator of the cover-up after the Watergate arrests. As the cover-up collapsed, Dean sought but did not receive immunity from Federal prosecution. Dean did receive immunity from the Senate and was the first insider to reveal the President's involvement in the cover-up. After pleading guilty to obstruction of justice and sentenced to a prison term of one to four years, he served four months in a witness holding facility. |

| H.R. "Bob" Halderman | Bob Haldeman was President Nixon's closest aide. After serving as chief of staff in the 1968 Nixon campaign, Haldeman became White House chief of staff in January 1969. Haldeman was convicted in the Watergate cover-up trial of conspiracy to obstruct justice, obstruction of justice and perjury. Sentenced to a term of between two and a half and eight years, he served 18 months in prison. |

| WATERGATE | |

The President's re-election committee, headed by Mitchell, had hired Liddy and paid for this break-in. Because Liddy's team included former White House Plumbers, an uncontrolled investigation could also lead back to the unethical and illegal domestic operations of 1971, including the Fielding break-in and Hunt's special projects with Colson. The actions by President Nixon and his chief lieutenants to keep those secrets away from criminal investigators would doom his presidency.

- The First Watergate Break-in

May 27, 1972

The Hunt-Liddy team broke into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at the Watergate late in the evening of May 27. They installed electronic taps on the telephones of DNC chairman Larry O'Brien and R. Spencer Oliver, another Democratic party official. The team left the Watergate building without being detected. - Second Watergate Break-in and Arrests

June 17, 1972

Magruder and Liddy pressured Hunt's team to break into the Watergate for a second time because the bug on O'Brien's phone did not work and the one placed on Oliver's phone was not producing any usable political intelligence. The Cubans were reluctant, as was Hunt, but the attempt was made. At 1:47 a.m. a building security guard, Frank Wills, noticed that the door from the stairwell into the garage had been taped open. He called the police and the five burglars were arrested

- Berard L. Barker

- Virgilio Gonzolaz

- Eugenio Rolando Martinez

- James W. McCord, Jr.

- Frank A. Sturgis

- What the FBI Finds the First Day

June 17, 1972

In the burglars' hotel rooms, the FBI found items that connected E. Howard Hunt to the break-in. Hunt's name and a White House telephone number appeared in two of the burglars' address books. The FBI also found stacks of crisp $100 bills, which the Bureau would eventually track to checks from contributors to the President's re-election campaign. - The Cover-up: Early Effects

June 17 - July 16, 1972

The President participates in the evolving cover-up and orders the CIA to obstruct the FBI's investigation. Through the Justice Department, the White House learned that the FBI had already traced the money found in the hotel rooms to checks cashed by burglar Bernard Barker in Miami. Haldeman suggested, citing a recommendation from John Mitchell and John Dean, that the President use the CIA to prevent the FBI from tracing the money from Barker to the re-election campaign. The plan involved ordering the CIA to mislead the FBI into believing that the Watergate break-in was a CIA operation. Haldeman also informed the President that his advisors had implemented a plan to get Hunt out of the country. The President approved the plan to use the CIA and raised no objection to keeping Hunt away from criminal investigators. - The Cover-up Begins

June 18-20, 1972

Liddy, Magruder and Strachan destroyed evidence of GEMSTONE planning and intelligence. Hunt disappeared. At Ehrlichman's direction the contents of Hunt's safe in the Old Executive Office Building (now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building), including evidence of his consulting work with Colson and Liddy, were sent to Dean. Liddy met Dean and reported on the Watergate problem. Meanwhile Mitchell, Ehrlichman, Haldeman, and Dean conferred separately and together on the next steps. - Payments to the Burglars

June 19, 1972

G. Gordon Liddy told John Dean that the burglars would keep quiet about what they knew, but they expected financial support. Dean, with Ehrlichman and Haldeman's authorization, arranged for payments by the President's lawyer, Herbert Kalmbach. From June 29 through September 19 the burglars' representatives received $217,000 from the President's re-election committee and one large private donation. Payments were dropped in unmarked envelopes at prearranged times and places. When Kalmbach concluded the payments were illegal, Mitchell's close aide Frederick C. LaRue assumed responsibility for the operation. The payments made after September 19 (a sum of at least $237,000) came from the White House's secret $350,000 political fund. LaRue, who received the money from Haldeman's aide Strachan, understood the payments were hush money to keep the burglars from implicating others. - Obstruction of Justice

June 23, 1972

In three different conversations, the President approved the use of the CIA to obstruct the FBI's criminal investigation. Ehrlichman and Haldeman subsequently told CIA director Richard Helms and his deputy, General Vernon Walters, that the CIA should instruct the FBI to back off its investigation of the source of the burglars' money for national security reasons. Although the CIA had not organized the Watergate break-in, Helms and Walters initially agreed to the Presidential request. - Cashiers Check Cashed by Barker

The White House did not want the FBI to investigate the political contribution form Kenneth Dahlberg. The check linked the re-election committee to the Watergate burglars. - The CIA Says No to the Cover-up

July 6, 1972

The CIA changed its mind and informed the FBI that national security was not involved in the Watergate affair. The CIA had earlier refused a White House request that it pay salaries and legal fees for Hunt and the Cuban Americans. On July 6, Acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray, told President Nixon that both the FBI and the CIA were concerned that some White House staffers were attempting to use the CIA to obstruct the Watergate investigation. The President told Gray that the FBI should press on with its investigation. - The Cover-up: Further Efforts

July 7 - September 15, 1972

With the CIA and FBI out of their control, President Nixon and his senior aides revised the cover-up scenario. The White House now hoped to shape the investigation so that federal prosecutors believed that Liddy had acted without the knowledge of campaign chief John Mitchell and his deputy Jeb Magruder. Skeptical that this would work, and certain that Magruder would have to be sacrificed to protect Mitchell, the President told aides on July 19 that he would pardon Magruder if he pled guilty. The President also said that he intended to pardon Hunt, Liddy, and the burglars after the election. The President devised a plan to pair these pardons with pardons for jailed members of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Meanwhile, Mitchell's staff worked with Dean to give money to the burglars' families. The President's personal lawyer, Herbert Kalmbach, started these payments on July 7 and the President expressed his approval on August 1.

If the CIA could deflect the FBI from Hunt, they would thereby protect us from the only White House vulnerability involving Watergate that I was worried about exposing - not the break-in, but the political activities Hunt had undertaken for Colson.- Richard Nixon 1978

What did the President know and when did he know it?

- Senator Howard Baker (R-Tennessee)

During the period when the cover-up was working, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post kept the Watergate story alive in the press. Using tips from Associate FBI Director Mark Felt - later revealed in 2005 as their source "Deep Throat" - and the products of their own reporting, the two journalists wrote articles that laid the groundwork for the Senate's decision to initiate its own investigation.

Meanwhile, Judge John J. Sirica, who presided over the Watergate grand jury, suspected that some of the witnesses were lying and looked for a way to get at the truth. In early 1973, some Watergate conspirators would start working with prosecutors.

| PRIMARY PARTICIPANTS: | |

|---|---|

| Woodward & Bernstein | Between June and October 1972, these two Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Cart Bernstein broke the news that

|

| Judge Sirica | John Joseph Sirica was appointed to the US District Court for the District of Columbia by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1957. As Chief Judge of that court between 1971 and 1974, he presided over both the Watergate burglary and cover-up trials. His rulings were upheld in every appeal from the Watergate cases. |

| Archibald Cox | Watergate Special Prosecutor hired May 25, 1973. Harvard Law Professor Archibald Cox was sworn in as the first Watergate Special Prosecutor. A former Solicitor General under President Kennedy. Cox was the fifth man asked by Attorney General Elliot Richardson to take the job. The Senate had made the appointment of an independent prosecutor a condition for confirming Richardson to replace Richard Kleindienst. |

| WATERGATE | |

November 7, 1972

President Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew defeated Senator George McGovern and Sargent Shriver, winning 49 states and 60.7 percent of the vote.

- The Court Only Indicts Seven

September 15, 1972

After the Watergate grand jury only charged Liddy, Hunt, and the five burglars with complicity in the illegal bugging operation (and did not indict Mitchell or his deputy, Magruder), President Nixon thanked John Dean for "putting your fingers in the dikes every time that leaks have sprung here and sprung there." "The whole thing is a can of worms," commented the President. - The First Watergate Trial

January 30, 1973

The jury found McCord and Liddy guilty of their participation in the Watergate break-in. Hunt, Barker, Martinez, Sturgis, and Gonzalez had all pleaded guilty at the start of the trial. Convinced that the defendants had lied to cover up for their superiors, Judge John J. Sirica would ultimately give the men very long but provisional sentences in the hope of encouraging them to cooperate with Government prosecutors and Senate investigators. - The Senate Forms a Select Committee on Watergate

February 7, 1973

By a vote of 77-0, the U.S. Senate formed the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, better known as the Senate Watergate Committee. Composed of four Democrats and three Republicans, the Senate Watergate Committee was chaired by Democratic Senator Sam J. Ervin Jr. of North Carolina. Republican Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr. of Tennessee was the ranking minority member. The Senate decided that the Committee would investigate only the 1972 campaign. - The Burglar Breaks His Silence

James W. McCord, Jr. was the first Watergate burglar to allege a cover-up

March 19, 1973

In a letter to Judge Sirica, Watergate burglar James McCord made four explosive charges

- There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent.

- Perjury occurred during the trial in matters highly material to the very structure, orientation, and impact of the government's case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants.

- Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying.

- The Watergate operation was not a CIA operation. The Cubans may have been misled by others into believing that it was a CIA operation.

- Dean and Magruder Begin to Cooperate with Federal Prosecutors

April 8 - 15, 1973

Seeking immunity from prosecution, John Dean and Jeb Magruder approached Federal prosecutors with information about Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Mitchell's role in the cover-up. Magruder revealed his own role in setting up Liddys intelligence operation and Dean also revealed the Plumbers' September 1971 break-in at Dr Fielding's office. A month later, a mistrial was declared in the Ellsberg trial and Daniel Elisberg was released from jail in the end, Dean and Magruder did not get immunity from the prosecutors. - Haldeman and Ehrlichman are Forced Out

April 30, 1973

After Dean and Magruder exposed the cover-up to prosecutors, President Nixon concluded that dramatic action was required to prevent the Watergate investigation from consuming his Presidency. He asked his two closest aides Haldeman and Ehrlichman, to resign. The President, who also fired John Dean and requested that Attorney General Richard Kleindienst leave, announced these departures in a televised address. - A Cancer on the Presidency

March 21, 1973

The White House's management of the Watergate issue reached a turning point when John Dean approached the President with his concerns that the cover-up was getting out of hand. E. Howard Hunt's lawyer, William Bittman, had just approached John Dean for additional payments for his client. During his meeting with President Nixon on March 21 1973, Dean warned that the cover-up was "a cancer on the Presidency." Instead of ordering an end to the cover-up, the President told Dean that one million dollars could be found to satisfy Hunt. - President's Denial

May 22, 1973

With senior members of the White House staff and the Re-Election Committee now implicated in the scandal, the President issued his most sweeping denial of any personal involvement. He declared that

- He knew nothing about the cover-up before the March 21 meeting with Dean

- He knew nothing about any payments to the convicted burglars

- He never authorized any pardons,

- He played no role in using the CIA to block the FBI investigation of the break-in

- John Dean Testifies

June 25, 1973

John W. Dean III began four days of televised testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee. The Committee, which comprised four Democrats and three Republicans, was formed in February 1973 and started televised hearings in May. After receiving immunity from the Senate Watergate Committee, Dean became the first White House official to claim publicly that President Nixon had participated in the Watergate cover-up. Dean revealed that the President knew about the payments to the Watergate burglars and E. Howard Hunt after they were arrested. Dean also revealed the existence of an "Enemies List" and the "Huston Plan."

With regard to the specific allegations that have been made, I can and do state categorically:

- I had no prior knowledge of the Watergate operation.

- I took no part in, nor was I aware of, any subsequent efforts that may have been made to cover up Watergate.

- At no time did I authorize any offer of executive clemency for the Watergate defendants, nor did I know of any such offer.

- I did not know, until the time of my own investigation, of any effort to provide the Watergate defendants with funds.

- At no time did I attempt, or did I authorize others to attempt, to implicate the CIA in the Watergate matter.

- It was not until the time of my own investigation that I learned of the break-in at the office of Mr. E specifically authorized the furnishing of this information to Judge Byrne.

- I neither authorized nor encouraged subordinates to engage in illegal or improper campaign tactics.

Richard Nixon and the nation have passed a tragic point of no return

-November 12, 1973

When Alexander Butterfield told the Senate Watergate Committee in mid-July 1973 that President Nixon had been secretly recording his conversations, the Watergate scandal entered a new phase. From that moment, the Senate, the Sirica Court, Special Prosecutor Cox, and many in the public viewed the White House tapes as the key to figuring out whether the President was telling the truth. The President, however, fought to prevent Congress or the Court from hearing the tapes, citing the Constitutional doctrine of executive privilege. Ultimately, the US Supreme Court would settle the fight over the tapes by ordering the President to turn over the tapes requested by the Special Prosecutor.

| PRIMARY PARTICIPANTS: | |

|---|---|

| Alexander P. Butterfield | Butterfield had a career in the Air Force before joining the White House in 1969. As deputy assistant to the President from 1969 to 1973, Butterfield handled the daily preparation of briefing materials for the President and oversaw the U.S. Secret Service. Butterfield supervised the Secret Service's installation of the the secret White House taping system in mid-February 1971. |

| Spiro T. Agnew | Vice President Agnew Resigned October 10, 1973 He pleaded no contest to several counts of accepting bribes. The bribes were unrelated to the Watergate scandal, but the Vice President's plea was a blow to public trust in the Nixon administration. Two days later, President Nixon nominated Congressman Gerald R. Ford of Michigan, the House minority leader, to be the 40th Vice President of the United States |

| Leon Jaworski | Named the New Special Prosecutor on November 1, 1973 Acting Attorney General Bork, named Leon Jaworski, a Texan and former president of the American Bar Association, as Cox's replacement. The President assured Jaworski of his independence. |

| Richardson, Bork, & Ruckelshaus | When the President ordered that Cox be fired, three Justice Department officials face a fateful decision.

|

| Gerald R. Ford | Appointed Vice President December 6 President Nixon selected House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford to replace Spiro Agnew after Republican leaders oppose the President's first choice, former Democratic Governor of Texas and U.S. Treasury Secretary John B. Connally, Jr. Vice President Ford took the oath of office on December 6, 1973, after confirmation by both the Senate and the House. Less than a year later, he became the first person to become U.S. President without being elected President or Vice President. |

| WATERGATE | |

President Ninon assumed, like the five presidents who secretly taped in the Oval Office before him, that he owned his White House tapes forever. After Butterfield disclosed the taping system, the President, who was recuperating from pneumonia, received conflicting advice:

- Vice president Spiro Agnew advised the President to build a bonfire.

- White House Counsel Leonard Garment argued that destroying the tapes could be seen as destroying evidence.

- Haldeman also argued for keeping the tapes, believing that they strengthened the White House's Watergate defense.

- Initially uncertain what to do, President Nixon ultimately decided to preserve the tapes and assert executive privilege to protect them from disclosure.

- The Special Prosecutor and the Senate Watergate Committee Demand Tapes

July 23, 1973

On the same day, Judge Sirica, on behalf of Cox, issued a formal demand - a subpoena - for nine White House tapes and the Senate issued a separate subpoena for the tapes. - Sirica's Decision

August 29, 1973

Judge Sirica rejected the President's argument that executive privilege allowed him to keep his tapes confidential. Judge Sirica ruled instead that the Court had to listen to the tapes to decide whether they were relevant to the Watergate criminal investigation. The President appealed the decision. - The Court of Appeals Upholds Sirica's Tapes Decision

October 12, 1973

The U.S. Court of Appeals noted that the President must hand over the tapes to Judge Sirica. The White House had until October 19 to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. - The Stennis Compromise

October 19, 1973

The White House announced that instead of appealing to the Supreme Court, the President would prepare edited summaries of the nine requested tapes for Judge Sirica. Only Senator John C Stennis, a Democrat from Mississippi would be allowed to very them, in exchange, the Special Prosecutor would not be permitted to request any other tapes. Cox rejected this plan on the grounds that the Court had the right to listen to the actual tapes and by limited any future requests, the plan also interfered with his ongoing investigation. - Saturday Night Massacre

October 20, 1973

The President set off a wave of public anxiety by ordering the firing of the Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox. After the Court of Appeals upheld Cox's demand for nine White House tapes on October 12, the Attorney General and the White House scrambled to find a compromise that would satisfy the President and Cox. When Cox announced on October 20 that he could not accept the so-called Stennis Compromise because it did not allow access to the actual tapes, the President instructed the Justice Department to fire him. Attorney General Elliott Richardson and his deputy William Ruckelshaus chose to resign rather than follow the President's order. Solicitor General Robert H. Bork, who was next in line, agreed to fire Cox. White House Chief of staff Alexander M. Haig Jr. directed the FBI to seal the offices of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force (WSPF). The WSPF, which was formally dissolved a few days later, was quickly re-established in early November. - The President Turns Over Some Tapes

October 23, 1973

Responding to the public fears caused by the Saturday Night Massacre, the President agreed to turn over the nine requested tapes to the Court and the Special Prosecutor. Included among the nine was the President's March 21, 1973 "cancer on the Presidency" conversation with John Dean. When Judge Sirica and the new Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski listened to it, they each concluded that President Nixon had participated in the cover-up.- An 18 1/2 Minute Gap

When the President agreed to turn the nine tapes over to Judge Sirica, two of the subpoenaed conversations turned out never to have been recorded and one - from June 20, 1972 - was found to include a controversial eighteen-and-a-half minute gap during a section dealing with Watergate. These omissions and the gap would raise serious questions about White House tampering with the tapes.

- An 18 1/2 Minute Gap

- Some Lawmakers and Members of the Public Started Calling for the President's Impeachment after the Saturday Night Massacre

February - March 1974

The Democratic leadership in the House gave the Judiciary Committee the responsibility for considering articles of impeachment. In February 1974, with only four dissenting votes, the entire House assigned broad investigative powers to the Judiciary Committee. On March 26, 1974, Judge Sirica handed over grand jury materials, including the "cancer on the Presidency" tape, to the House for its investigation.- Un-indicted Co-Conspirator

The Watergate grand jury, which heard the "cancer on the Presidency" tape, named President Nixon as an "unindicted co-conspirator" in the Watergate cover-up. Originally sealed, this action later leaked.

- Un-indicted Co-Conspirator

- The White House Releases Some Transcripts

April 1974

In a televised address on April 30 1974, President Nikon announced the release to the House Judiciary Committee of 1,308 pages of edited transcripts, covering 46 White House meetings and telephone conversations. Since this release did not include the key tapes that the Special Prosecutor wanted, Judge Sirica ruled that the actual tapes were required and Jaworski's request headed to the Supreme Court.- Jaworski Wants More Tapes

April 16, 1974

The new Watergate Special Prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, requested 64 more tapes, seven times as many tapes as Cox had wanted.

- Jaworski Wants More Tapes

- The Supreme Court Rules Against the President

July 24, 1974

In a unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Judge Sirica's order that the President hand over the 64 recordings requested by the Special Prosecutor. Late that afternoon, President Nixon agreed to abide by the decision and had his legal team prepare transcripts of those conversations. Over the next two weeks, as some White House aides and congressional allies of the President began to learn about what was in these transcripts, the President's last level of support began to erode. The President, however, decided to await the public's response to the release of the new transcripts before deciding how to proceed. - Articles of Impeachment

July 27, 1974

Bipartisan Majorities in the Judiciary Committee Support Three Articles of Impeachment. With the support of every Democrat and nearly half of the Republicans, the House Judiciary Committee voted to recommend three articles of impeachment be approved by the House of Representatives.

- Presidential obstruction of justice

- Governmental abuse of powers

- Failure to comply with House subpoenas

- The Effect of "the Smoking Gun" Conversations

August 5, 1974

When the White House released transcripts on August 5 of three conversations from June 23, 1972, the public learned for the first time that the President had ordered the CIA to obstruct the FBI's investigation. These transcripts, popularly known as "the Smoking Gun," contradicted the President's public defense and undermined his remaining support on Capitol Hill. Every Republican member of the House Judiciary Committee who had voted for the President in committee announced that they now supported impeachment. At the same time, the President's support in the Senate, where he would be put on trial once the House recommended impeachment, collapsed. Three veteran Republican leaders - Senators Hugh Scott, Barry Goldwater, and Congressman John Rhodes - met with the President on August 7 to deliver the news. Meanwhile, the President's public approval rating fell to 24 percent.

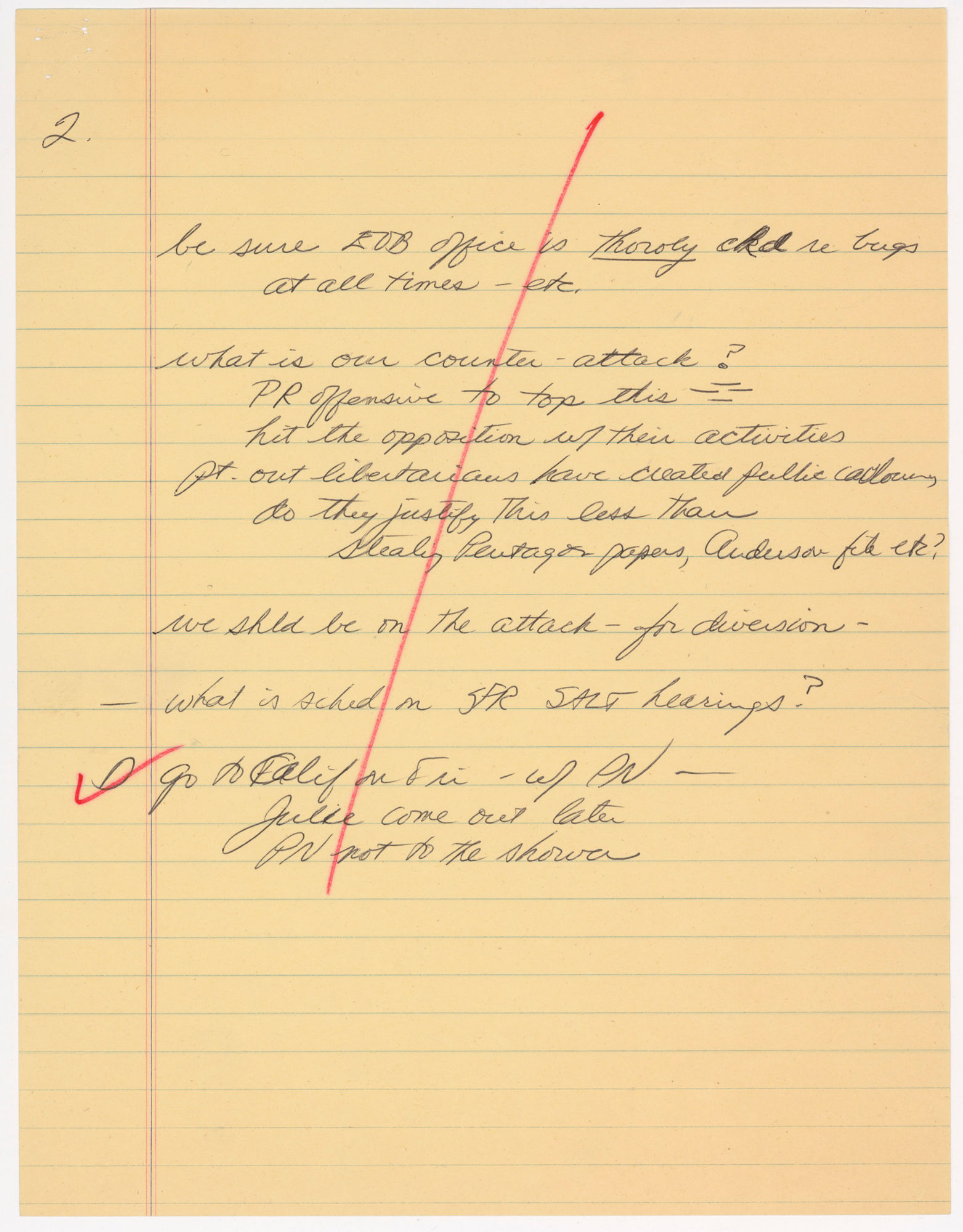

On November 21, 1973, White House lawyers informed Judge John J. Sirica, who was presiding over the Watergate cover-up trial, that there was an eighteen and a half minute gap in a recording made of a conversation between the President and White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman on June 20, 1972. There were no voices during the gap, just buzzing and clicking noises. Archibald Cox, the first Watergate Special Prosecutor, had subpoenaed this recording in July 1973.

- Why Does the Gap Matter?

The gap occurs during a recording of the President and Haldeman's first conversation in Washington, D.C. after the Watergate break-in. President Nixon was in the Bahamas and Haldeman in Florida on June 17, 1972, when the five burglars were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee headquarters. On June 20, 1972, Haldeman met with the President in the Old Executive Office Building. A comparison of Haldeman's handwritten notes of that conversation with the actual recording shows that the gap begins just as the men start discussing the Watergate break-in and how to respond. The disclosure of the existence of this gap in the White House tapes led to public skepticism in 1973 and still raises questions about how the gap happened and what was erased. - Can we Recover the Missing Converstation?

In 1974, the Court-appointed experts wrote "we know of no technique that could recover intelligible speech from the buzz section." Between 2001 and 2003, the National Archives and Records Administration sponsored an investigation to determine if newer technology could recover information from the gap. In 2009, NARA launched an effort to use hyperspectral imaging, video spectral comparison, and electrostatic detection analysis to examine Haldeman's notes of the meeting for latent or indented images of additional notes that might have been written on the same legal pad. Neither effort revealed or recovered additional content. Perhaps future advances will unlock the secrets of the gap. - Who Erased the Tape?

On November 27, 1973, the President's longtime secretary Rose Mary Woods testified that she had accidentally caused the first five minutes of the gap when she reached for a telephone call while transcribing the tape. Woods recalled pressing the 'record" button down by mistake and thought she might have also kept her foot on the machine's operating pedal during the entire five-minute call. No one took responsibility for the remainder of the gap and Woods had difficulty recreating this stretch for the Sirica Court. Six audio experts appointed by the Court reported in 1974 that the gap was the result of at least five and possibly nine separate erasures; these erasures could not have been caused by using the pedal; and the tape showed evidence of being erased, rewound, and erased again.

- The Gap occurred during the President's 11:26 a.m. meeting.

[]

[https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/virtuallibrary/documents/PDD/1972/078%20June%2016-30%201972.pdf]

- The gap in the recorded conversation begins at the end of the first page.

[]

[https://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2011/nr11-142.html]

- Stretching to illustrate how an accidental erasure might have occurred.

- How she might have cause part of the gap.

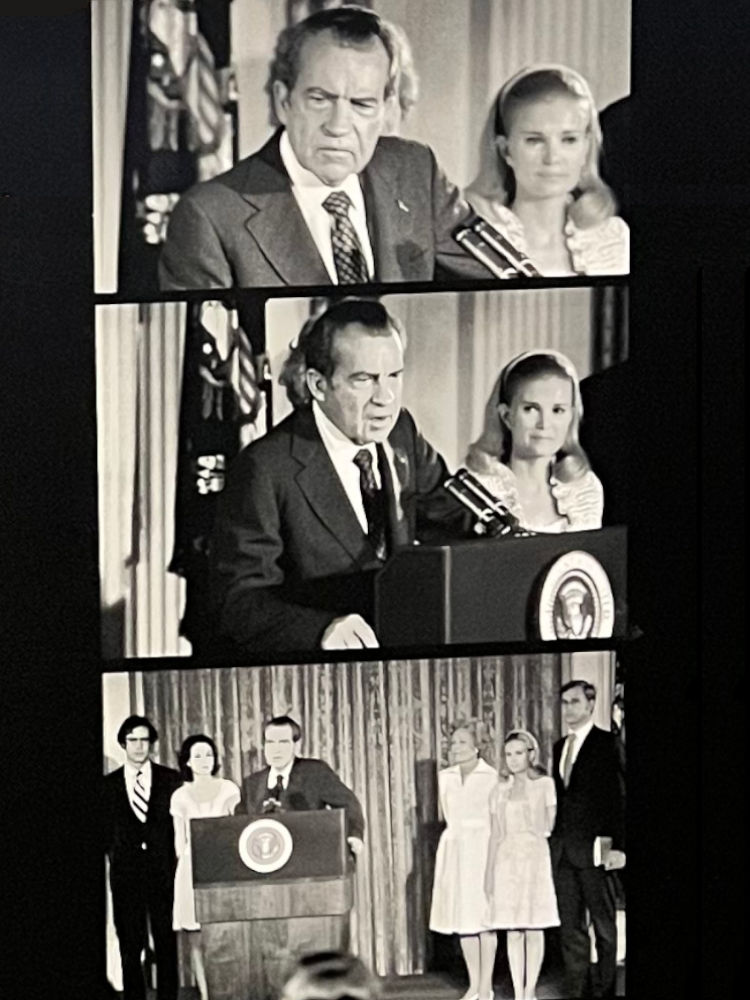

President Nixon announced on August 8, 1974, that he would resign at noon the next day. At a tearful farewell to his staff the next morning in the East Room, the President observed:

Always remember, others may hate you, but those who hate you don't win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.

Our long, national nightmare is over. Our Constitution works; our great republic is a government of laws and not of men.- President Gerald R. Ford, August 9, 1974

On September 8, 1974, President Gerald Ford granted former President Nixon, "a full, free, and absolute pardon" for "all offenses against the United States" that he "has committed or may have committed" as President. President Ford believed that putting Richard Nixon on trial would only prolong the trauma of Watergate and the country needed to start healing.

What really happened in Watergate is that the system worked.- Carl Bernstein

I came away feeling much better, frankly, about our system of government and the constitution and the people in general. We came through a crisis because of that.- Law clerk to Judge John Sirica

I didn't want to make myself believe that President Nixon did this, that he actually participated .. it was a tragic chapter in political history.- Senator Bob Dole (R-Kansas) Chairman of the Republican National Committee, 1971 - 1973

In the decade following President Nixon's resignation, the U.S. Congress passed laws to address the abuses of Governmental power and campaign irregularities uncovered by Senate and House investigators. The new laws limited the Federal Government's ability to collect information on private citizens, reformed the campaign finance system, and strengthened public control of and access to Presidential records. Not only did the Congress act to preserve the famous Nixon White House tapes, but it also established an independent agency, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), to protect all Government documents. NARA administers the libraries of all modern Presidents.

- Privacy Act of 1974

- Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act of 1974

- 1974 Amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act

- 1974 Amendments to the Freedom of Information Act

- Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978

- Presidential Records Act of 1978

- Ethics in Government Act of 1978

- Independent Counsel Act of 1978

- National Archives and Records Administration Act of 1984

Our Government consists of three equal branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary. Since deciding Marbury v. Madison in 1803, the U.S. Supreme Court has exercised the power of judicial review over the actions of the Executive and Legislative branches of the U.S. Government.

In the summer of 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court considered the question of whether the U.S. Constitution permitted President Nixon to withhold the White House tapes from a federal court. At issue was whether a President's right to have confidential conversations with advisors - as a matter of "executive privilege" - outweighed the judiciary's need for access to records of those conversations for a criminal investigation.

- After his oral argument before the Supreme Court on July 8, 1974, Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski sent a letter to the Supreme Court explaining why he could not accept President Nixon's offer to hand over only the tapes of the portions of the subpoenaed conversations that had appeared among the transcripts published by the White House in April 1974. The April 1974 transcripts included selections by the White House from just 20 of the 64 conversations that Jaworski had requested. In this letter, Jaworski asked the Supreme Court to rule on the disposition of all 64 tapes.

- On July 15, 1974, James D. St. Clair, the Special Counsel to the President, responded to the Supreme Court that President Nixon did not authorize releasing "those portions of the recorded conversations that were not published."

The framers of the Constitution had in mind a strong presidency ... The President is not above the law by any means; but the law as to the President has to be applied in a constitutional way, which is different than anyone else. The President of the United States, we suggest, can be proceeded against only by impeachment while in office and his powers are unabated until such time as he leaves that office.- James D. Se Clair, Special Counsel to the President, July 8, 1974

This nation's constitutional form of government is in serious jeopardy if the President, any President, is to say that the Constitution means what he says it does and that there is no one, not even the Supreme Court, to tell him otherwise.- Leon Jaworski, Watergate Special Prosecutor, July 8, 1974

Neither the doctrine of separation of powers nor the generalized need for confidentiality of high-level communications, without more, can sustain an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances.

Warren E. Burger, Chief Justice of the United States, July 24, 1974

| PRIMARY PARTICIPANTS: | |

|---|---|

| A Unanimous Decision from the Supreme Court On July 24, 1974, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision in U.S. v. Nixon, affirming that President Nixon had to release all materials under subpoena to District Court Judge John J. Sirica. The vote was 8-0: Justice William Rehnquist, a former Nixon administration official, had recused himself. | |

| Associate Justice William O. Douglas | Nominated by Franidin D. Roosevelt, sworn in on April 16, 1939 |

| Associate Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. | Nominated by Dwight D. Eisenhower, swor in on October 15, 1956 |

| Associate Justice Potter Stewart | Nominated by Dwight D. Eisenhower, sworn in on October 13, 1958 |

| Associate Justice Byron R. White | Nominated by John F. Kennedy, sworn in on April 15, 1962 |

| Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall | Nominated by Lyndon B. Johnson, sworn in an October 1, 1967 |

| Chief Justice Warren E. Burger | Nominated by Richard Nixon, sworn in on June 22, 1969 |

| Associate Justice Harry A. Blackmun | Nominated by Richard Nixon, sworn in on June 8, 1970 |

| Associate Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. | Nominated by Richard Nixon, sworn in on January 6, 1972 |

| Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist | Nominated by Richard Nixon, sworn in on January 7, 1972 |

| WATERGATE | |

When former President Richard Nixon arrived in California in August 1974, he intended to tell his side of the Watergate story someday. Although his Presidential papers and tapes would remain in the custody of the U.S. Government, President Nixon and his research assistants were permitted to consult these records.

In 1977, President Nixon broke his public silence on Watergate by participating in an internationally syndicated television interview with the British broadcaster David Frost. A year later Grosset & Dunlap published RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon.

It was in these days at the end of June and the beginning of July 1972 that I took the first steps down the road that eventually led to the end of my presidency. I did nothing to discourage the various stories that were being considered to explain the break-in, and I approved efforts to encourage the CIA to intervene and limit the FBI investigation. Later my actions and inactions during this period would appear to many as part of a widespread and conscious cover-up. I did not see them as such. I was handling in a pragmatic way what I perceived as an annoying and strictly political problem. I was looking for a way to deal with Watergate that would minimize the damage to me, my friends, and my campaign, while giving the least advantage to my political opposition.

- Richard Nixon, on the Watergate Coverup

I do not believe I was told about the break-in at the time, but it is clear that it was at least in part an outgrowth of my sense of urgency about discrediting what Ellsberg had done and finding out what he might do next. Given the temper of those tense and bitter times and the peril I perceived, I cannot say that had I been informed of it beforehand, I would have automatically considered it unprecedented, unwarranted, or unthinkable.

- Richard Nixon, on the 1971 Fielding Break-in

If there was any campaign advantage to incumbency, it had to be access to government information on one's opponents. I remembered the IRS leaks of my tax returns to Drew Pearson in the 1952 campaign and the politically motivated tax audits done on me in 1963.

- Richard Nixon, on the Political use of the IRS

Since the 1970s, the public and the media have attached the suffix -gate to major American political scandals. Why did Watergate sear itself into the public imagination and our history? And what is its legacy for us today? Did public expectations about the use of Presidential power change because of Watergate? What, if anything, can it teach us about our rights as citizens and the workings of our Constitution?