Siege of Washington

Siege of Washington

The Battle of Washington, aka Siege of Washington, took place from March 30 to April 20, 1863, in Beaufort County, North Carolina, as part of Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's Tidewater operations during the American Civil War (1861-1865).The Southerners would fail in their attempt to dislodge the Federals in Washington, NC during 1863 but they would succeed in April of 1864. Then they relinquished the city once more to the Federals in November of that year. Washington would remain under Union occupation for the remainder of the war.

https://www.google.com/maps/place/Washington,+NC

https://www.google.com/maps/place/Washington,+NC

https://www.google.com/maps/@35.5490859,-77.0562929,15z?hl=en

At the start of the Civil War, "Little" Washington, N.C. was an important river port and the hiding place for the Cape Hatteras Light's Fresnel lens. In the summer of 1861, Lightkeeper Benjamin Fulcher was ordered to dismantle the lens and have it shipped to Washington to be hidden in John Myers' riverfront warehouse. Federal forces captured the town on March 21, 1862, hoping to recover the lens and shutdown the port. But the previous day Southern loyalist Dr. David T. Tayloe, whose family is still prominent in town, had the day before ushered the lens up the Tar River by steamboat into the interior of N. C.

Because of its significance as a port, the Confederates made several attempts to unshackle Washington from its Union occupiers. The Battle of Washington was the second attempt by the Confederate Army to liberate the town.

At day break on September 6, 1862, Confederate Maj. Stephen D. Pool, who previously directed the defense of Fort Macon, led 1,000 North Carolina Confederate infantry, cavalry, and artillery troops against a Union garrison of 1,200 men. The Confederates surprised Union pickets stationed on the west side of town near the Elmwood Plantation which today is the area west of Washington Street from the Tar River north to U.S. 264. After a brief skirmish, the North Carolina troops charged down Second Street while the cavalry rushed down Market. At the corner of Second and Bridge Streets, a Union battery was captured and the troops advanced further into town. Though surprised, the Union forces regrouped and attacked west down Main, Second, and Third Streets pushing the Confederates back as far as Bridge Street.

Meanwhile the Union gunboats, Picket and Louisiana, anchored abreast the town in the Tar River, engaged the Confederates by shelling the west end of town. Unexpectedly, the Picket's shell magazine exploded, sinking the gunboat and killing the captain and 19 of the crew. Today the remains of the Picket lie just west of the U.S. 17 Business bridge on the bottom of the Tar River.

After more than 2 hours of hard fighting, the Confederate forces withdrew. Confederate casualties were 31 killed, 30 wounded, and 24 taken prisoner, while the Union lost 26 killed, 55 wounded, and 12 captured. There were some reports of civilian casualties. Following the encounter, the union garrison was forced to strengthen the defenses around the town allowing them to maintain the occupation until they withdrew from Washington on April 30, 1864.

It, along with Plymouth in Washington County, suffered more Civil War destruction than any other North Carolina town.

The scars of the Civil War are still visible in Washington NC. Crossing the Pamlico River on Highway 17 look off to the west and you will see the remains of the Union Army's ship, Picket, jutting from the Tar River where it blew up on September 6th, 1862. Driving down Main St. you will view houses with dates of construction in the 1850's 60's and 70s', testimony to the fact that the town was burnt by Union troops during their evacuation after the fall of Plymouth, NC. Even more startling are the two houses on Water Street which were built in 1780 and 1795. They stood through the fires and barrages of the war, having cannon balls imbedded in their walls, a bequest of the shelling of the town by the Rebel troops located on the southern shore of the Pamlico River.

War came to Washington in March of 1862 when federal troops, escorted by the gunboat Picket, arrived at Washington. According to Charles Warren "Two companies and a band marched from the wharf to the courthouse playing national aires."

The Confederate force of infantry and cavalry troops slipped into the town on the morning of September 6, 1862 surprising the Federal troops and capturing their artillery. Federal cavalry, on their way to Plymouth, were alerted to the attack by the sound of gunfire. Charging up Main Street they clashed with Confederate cavalry at Market Street. A furious battle ensued with both sides advancing and retreating. Meanwhile mysteriously the Federal ship, the Picket, blew up killing the captain and nineteen crewmen.

In the spring of 1863, Confederate troops needing food and supplies for Lee's armies in Virginia, placed Washington under siege and several skirmishes resulted. The Confederate Armies were able to resupply the troops in Virginia without any serious intervention from the Federal troops in Washington.

When threatened, the union forces blew up their naval supplies, causing a fire that swept through the town destroying most of the early historic buildings. The war left the town devastated. Washington was rebuilt but suffered another fire in September 1900.

April 30, 1864 "The fire was set at Haven's Wharf... to destroy naval stores, cotton etc. to prevent falling into the hands of the Confederates." An eye witness account by Charles F. McIntire, Company G, 44th Massachusetts Infantry. "The fire rapidly spread north across Main Street, down Van Norden Street, consuming everything to Fifth- the last street in town... it burned the length of Gladden and Respess streets... every home on Bridge went down."

"Furiously the fire raged from Bridge Street down Second sweeping everything in its path to Respess St... Chimneys were all that was left of homes where only defenseless, though brave, women and children had lived." Other fires were lit by soldiers in Union uniforms at non-military facilities according to reports by locals after the war.

(L) Marsh House 1795, (R) Myers House 1780:

These two Federal style homes face Festival Park and the Pamlico River beyond in the Washington Historic District (National Register of Historic Places 1979, listing 79001661).Myers house, built 1780, is the oldest building in Washington, and Marsh house was built only 15 years later. Each house remained in the family of its builder approximately 150 years. Both were used by Federal troops as offices and quarters during the American Civil War, when much of Washington was destroyed by fire.

February-June 1862

After the culmination of Burnside's North Carolina Expedition little attention had been given to North Carolina by the Confederate Army.

March 20, 1862:

Union forces had captured Washington, North Carolina, just days after it captured New Bern during the Burnside Expedition.

September 6, 1862:

A small expedition under the command of Confederate Colonel S. D. Pool arranged for an attack on the Federal garrison at Washington, N.C., with the objective to retake the town.

This town was held by a force under Colonel Potter, of the First North Carolina Union Cavalry.

Pool's force consisted of two companies from the Seventeenth North Carolina Regiment, two companies from the Fifty-fifth North Carolina under Capt. P. M. Mull, 50 men under Captain MacRae from the Eighth North Carolina, and 70 men of the Tenth North Carolina Artillery acting as infantry and commanded by Captain Manney.

This force dashed into Washington in the early morning, surprising the garrison, and after a hot fight withdrew, taking several captured guns.

The Union gunboat Picket, stationed there, was blown up just as her men were called to quarters to fire on the Confederates, and nineteen of her men were killed and wounded.

The Confederates inflicted in this action a loss of 44, and suffered a loss of 13 killed and 57 wounded.

This was truly a North Carolina fight, the Brothers War, as all the participants were from this State.

December 1862:

A Union expedition from New Bern destroyed the railroad bridge at Goldsboro, N.C. along the vital Wilmington and Weldon Railroad.

This expedition caused only temporary damage to the railroad, but did prompt Confederate authorities to devote more attention to the situation along the coast of Virginia and North Carolina.

Following the Confederate victory at Fredericksburg, December 1862, General Robert E. Lee felt confident enough to dispatch a large portion of his army to deal with Union occupation forces along the coast. The whole force was put under the command of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. While Longstreet personally operated against Suffolk, Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill, March 1863, led a column which moved against Federal garrisons at New Bern and Washington, North Carolina. Maj. Gen. John G. Foster, commanding the Department of North Carolina, was responsible for the overall defense of the Union garrisons along the North Carolina coast. After Hill's attack against New Bern failed in April 1863, Foster arrived in Washington to take personal command of the garrison.

Plymouth, Washington, New Bern

In 1862 a Boston Journal correspondent described Washington as an agreeable town of about 2,500 residents "some two thirds of whom have seen fit to leave for the interior."

When forces under Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside, arrived on March 21, the remaining citizens "met the troops with every expression of welcome."

So prevalent were the Union sentiments that Burnside stationed troops from the 24th Massachusetts Regiment and several gunboats at the town, effectively occupying Washington.

In 1862 a Boston Journal correspondent described Washington as an agreeable town of about 2,500 residents "some two thirds of whom have seen fit to leave for the interior."

When forces under Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside, arrived on March 21, the remaining citizens "met the troops with every expression of welcome."

So prevalent were the Union sentiments that Burnside stationed troops from the 24th Massachusetts Regiment and several gunboats at the town, effectively occupying Washington.

In March 1863 Confederate General Daniel Harvey Hill launched an attack on the federal garrison at Washington in an attempt to reclaim the city. Confederates seized one battery and fortified others with the intention of launching an artillery bombardment. In the Pamlico River, piles that were cut off below the water line and other sunken impediments made for perilous river travel. Union General J. G. Foster and his men had made it into Washington just prior to Hill's placement of troops along roads to prevent federal reinforcements from reaching the garrison. The armies engaged in artillery attacks off and on for until mid-April when the Escort, a Union steamer, twice ran past the Confederate batteries. The arrival of supplies and reinforcements having bolstered the federal garrison, Hill withdrew his troops from Washington.

Washington remained under federal control until April 26, 1864, when, as a result of the Confederate victory at Plymouth, Brigadier General Edward Harland was ordered to withdraw from the town. For four days the evacuating troops pillaged Washington, destroying what they could not carry. As the final detachments were preparing to leave Washington on April 30, a fire started in the riverfront warehouse district, spreading quickly, until about one half of the city was in ashes.

General Robert F. Hoke entered Washington finding "a ruined city...a sad scene—mostly...chimneys and Heaps of ashes to mark the place where Fine Houses once stood, and the Beautiful trees, which shaded the side walks, Burnt, some all most to a coal." Hoke left the 6th North Carolina to defend Washington and to assist its citizens. A reversal of fortune would come in November 1864. Following the Union's recapture of Plymouth, Washington and the whole sound region, again fell under federal control.

To protect Confederate supply lines and to gather much-need provisions in eastern North Carolina, Gen. Daniel H. Hill planned demonstrations against Union-occupied New Bern and Washington in March 1863. He acted under orders from Gen. James Longstreet, whom Gen. Robert E. Lee had appointed commander of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina. After Hill's expedition to New Bern ended with no result, he marched to Washington and, on March 30, besieged the town and its Federal garrison. Union forces had held Washington since March 20, 1862, just five days after it captured New Bern.

The Confederates occupied Fort Hill, located five miles down the Pamlico River, and kept Washington from being reinforced with holding a small armada of Federal warships at bay. Action across the river at Rodman's Quarter stayed lively as the town was bombarded and the Confederate cannons dueled with the gunboats Commodore Hull, Louisiana, Eagle, and Ceres. Gen. Francis B. Spinola and his 8,000 troops tried to take Fort Hill from the Confederate forces but was repulsed on April 9 at the Battle of Blount's Creek.

Union reinforcements ended the siege on April 20, as Lee recalled Hill to Virginia. Supplies had been obtained, the Federals at Washington and New Bern had been kept occupied, and soon the Battle of Gettysburg would await both sides.

Captions:

Left: Rebel batteries and the National defenses during the siege of Washington, N.C.

Upper Right: "Shelling of rebel batteries in the woods opposite Washington, N.C. April 16, 1863." Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 16, 1863

Lower Right: "Siege of Washington, N.C. — Effect of two shells, fired at the same, on a rebel cotton battery, opposite Washington , N.C. April 12, 1863." Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 16, 1863

https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p15012coll8/id/10871

Sketch showing the position of the attacking and defending forces at the siege of Washington, N.C., March 29 to April 16, 1863

Foster, a West Point trained Army engineer, put his skills to good use improving the town's defenses as well as employing the use of three gunboats in the defense. By March 30, the town was ringed with fortifications, and Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett's brigade began the investment of Washington. Meanwhile, Hill established batteries as well as river obstructions along the Tar River to impede reinforcements. He also posted two brigades south of Washington to guard for any relief efforts coming overland from New Bern.

The Confederates sent a reply to Foster demanding surrender. Foster replied saying:

If the Confederates want Washington, come and get it.

Despite this defiance, Foster lacked the strength to dislodge the besiegers, and Hill was under orders to avoid an assault at the risk of sustaining heavy casualties. Thus, the engagement devolved into one of artillery, and even so the Confederates limited their bombings to conserve their ammunition. In time both sides were running low on supplies, and conditions grew miserable in the rain and mud. Despite the lack of progress against Washington, Hill was accomplishing a vital objective in the form of foraging parties so long as the Federals were pinned down.

A Federal relief column under Brig. Gen. Henry Prince sailed up the Tar River. Once Prince saw the Rebel batteries, he simply turned the transports around. A second effort under Brig. Gen. Francis Barretto Spinola moved overland from New Bern. Spinola was defeated along Blount's Creek and returned to New Bern. Foster decided that he would escape Washington and personally lead the relief effort leaving his chief-of-staff, Brig. Gen. Edward E. Potter in command at Washington.

On April 13, the USS Escort braved the Confederate batteries and made its way into Washington. The Escort delivered supplies and reinforcements in the form of a Rhode Island regiment. It was aboard this ship on April 15 that Foster made his escape. The ship was badly damaged and the pilot mortally wounded, but Foster made it out.

About the same time Foster made an escape, Hill was faced with numerous reasons that ultimately led to his withdrawal:

- The completion of his foraging efforts

- Union supplies reaching the Federal garrison

- A message arrived from Longstreet requesting reinforcements for an assault on Suffolk

Hill broke off the siege on April 15 and began to withdraw Garnett's brigade fronting Washington's defenses.

Meanwhile, Foster had made it back to New Bern and immediately began organizing a relief effort. He ordered General Prince to march along the railroad towards Kinston to hold off Confederates in the vicinity of Goldsboro, while Foster personally led a second column north from New Bern towards Blount's Creek where General Spinola had earlier been turned back. On April 18, Foster ordered Spinola to drive the Confederates from their road block at Swift Creek guarding the direct road from Washington to New Bern. At the same time, General Henry M. Naglee attacked the Confederate rear guard near Washington capturing several prisoners and a regimental battle flag. On April 19th Foster returned to the Washington defenses and by April 20 the Confederates had completely withdrawn from the area.

Apart from raids conducted by Foster and Potter, North Carolina remained relatively quiet until 1864 when Robert E. Lee was able to spare troops for another operation against Union enclaves along the coast.

When the Confederates later moved on and captured Plymouth, North Carolina, mid-April 1864, it would lead to the complete Federal withdrawal from nearby Washington on April 28, 1864. During the evacuation, the town was intentionally burned by Federal troops. Union Gen. Palmer, in an order condemning the atrocities by his troops, used these words:

It is well known that the army vandals did not even respect the charitable institutions, but bursting open doors of the Masonic and Odd Fellows' lodge, pillaged them both and hawked about the streets the regalia and jewels. And this, too, by United States troops! It is well known that both public and private stores were entered and plundered, and that devastation and destruction ruled the hour.

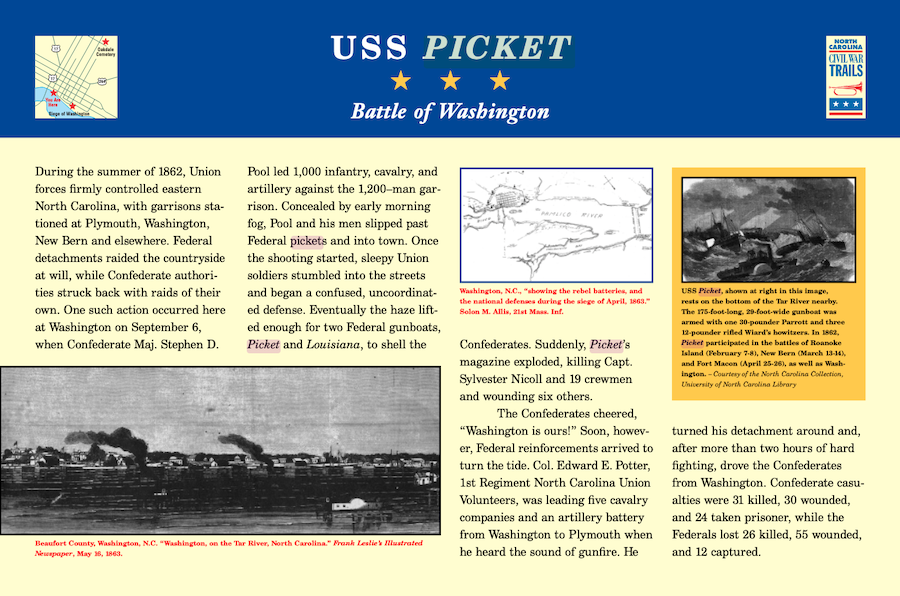

Battle of Washington

During the summer of 1862, Union forces firmly controlled eastern North Carolina, with garrisons stationed at Plymouth, Washington, New Bern and elsewhere. Federal detachments raided the countryside at will, while Confederate authorities struck back with raids of their own. One such action occurred here at Washington on September 6, when Confederate Maj. Stephen D. Pool led 1,000 infantry, cavalry, and artillery against the 1,200–man garrison.

Concealed by early morning fog, Pool and his men slipped past Federal pickets and into town. Once the shooting started, sleepy Union soldiers stumbled into the streets and began a confused, uncoordinated defense. Eventually the haze lifted enough for two Federal gunboats, Picket and Louisiana, to shell the Confederates. Suddenly, Picket's magazine exploded, killing Capt. Sylvester Nicoll and 19 crewmen and wounding six others.

The Confederates cheered, "Washington is ours!" Soon, however, Federal reinforcements arrived to turn the tide. Col. Edward E. Potter, 1st Regiment North Carolina Union Volunteers, was leading five cavalry companies and an artillery battery from Washington to Plymouth when he heard the sound of gunfire. He turned his detachment around and, after more than two hours of hard fighting, drove the Confederates from Washington. Confederate casualties were 31 killed, 30 wounded, and 24 taken prisoner, while the Federals lost 26 killed, 55 wounded, and 12 captured.

Caption:

Upper Left: USS Picket, shown at right in this image, rests on the bottom of the Tar River nearby. The 175-foot-long, 29-foot-wide gunboat was armed with one 30-pounder Parrott and three 12-pounder rifled Wiard's howitzers. In 1862, Picket participated in the battles of Roanoke Island (February 7-8), New Bern (March 13-14), and Fort Macon (April 25-26), as well as Washington. – Courtesy of the North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina Library

https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p15012coll8/id/10875/rec/3

Longstreet's Tidewater Operations:

Longstreet's Tidewater Operations:In mid-February, 1863 most of Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet's corps was moved south by rail. Confederate President Jefferson Davis made three purposes clear to General Longstreet:

- Longstreet was to keep himself able to cover Richmond in case the Union landed troops at Fort Monroe and moved up the James-York Peninsula again

- Be able to move back to Fredericksburg in case Major General Joseph Hooker moved

- Push the Union troops back to their bases, capture any of those ports if possible, gather all the provisions and volunteers possible in the area, which had been under Union occupation for almost a year.

Longstreet had to be careful not to get drawn into pointlessly bloody battles in this little campaign. This may be why General Robert E. Lee chose Longstreet over Stonewall Jackson, who had more experience in independent operations. Longstreet's Tidewater Operations battles were inconclusive and resulted in total estimated casualties of 1,160 for the entire siege.

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/longstreets-tidewater-operations

Town taken by Federals, March, 1862. Confederate efforts to recapture it failed, 1862 and 1863.

| Other Civil War Markers in Washington: |

|---|

| http://www.ncmarkers.com/search.aspx |

Burning of Washington The town was burned and shelled by evacuating United States troops in April, 1864. |

Fort Hill Site of Confederate batteries on Pamlico River which enabled Gen. D. H. Hill's forces to besiege Washington in spring of 1863. 5 mi. E.Fort Hill was a Confederate installation on the Pamlico River at Hill's Point six miles south of Washington. In the spring of 1863, while Union troops occupied Washington, Confederate General D. H. Hill and his men used Fort Hill as a base for their siege of the town. While Hill's men did not regain Washington from the Union Army, they did make evident the continued threat of Confederate forces in the Beaufort County region. Fort Hill was of reduced importance outside of the siege though, as other forts in the region proved more critical to both Union and Confederate goals. After the earthworks were completed in 1861, Confederate supplies proved to be too limited to supply the fort. The consequence was limited Confederate resistance against Union soldiers, who overtook and occupied Washington from 1862 until 1864. Nonetheless, during the Confederate siege of 1863, Fort Hill was equipped with two rifled 32-pound cannons, three smoothbore 32-pound cannons, and two 24-pound cannons. Throughout its existence, Confederate Companies B and I of the 3rd North Carolina Artillery units garrisoned. Between March 30 and April 16, 1863, Confederate forces attempted to regain control of Washington. Despite his superior fighting forces, Hill never attacked Washington directly, instead blockading the town and Union garrison from supplies. Fort Hill was utilized extensively in Hill's attack plan, with most of the fighting occurring between the Confederate batteries at Fort Hill and Union gunboats on the Pamlico River. Hill developed his plan of action for the siege of Washington around goals independent of regaining control of the town. Rather, the Confederate goals were to gather supplies from the surrounding counties and to maintain a presence in the region, keeping the Union forces on the defensive. Union forces maintained control of Washington until 1864, when they abandoned and burned the town. |

Daniel Harvey Hill Lieutenant General, C.S.A.; Supt. N.C. Military Institute in Charlotte; Davidson College professor; Editor, "The Land We Love." Grave is here.Daniel Harvey Hill served North Carolina and the Confederacy as a general and, after the Civil War, took a leading role in shaping the memory of the conflict. He was born July 12, 1821, in York County, South Carolina, to Solomon and Nancy Hill. He was the youngest of eleven children. Hill attended West Point where he graduated in 1842 at the age of twenty. He served with distinction in the Mexican War and rose to the rank of major. In 1848 he married Isabella Morrison, daughter of Davidson College president Robert Hall Morrison, making him brother-in-law to Stonewall Jackson. In 1849 Hill resigned from the army and became a professor of mathematics at Washington College in Virginia where he taught until 1854 when he then took a teaching job at Davidson. |

Battle of Plymouth Confederate troops led by Gen. Robert F. Hoke, aided by ram Albemarle, retook Union-occupied town, April 17-20, 1864.At 4 P.M. on April 17, 1864, an advanced Union patrol on the Washington Road was captured by Confederate cavalry. A company of the 12th N. Y. Cavalry attacked the Confederates, but was repulsed. Soon a large force of Confederate infantry appeared on the Washington Road, and at the same time Fort Gray, two miles above Plymouth on the river bank, was attacked by advanced Confederate infantry. During the evening skirmishing continued from the Washington Road to the Acre Road. Union General Henry W. Wessells' garrison of about 3,000, which had held Plymouth since December, 1862, was under attack by General Robert F. Hoke's Division of over 5,000 men. At 5:30 A.M. on April 18, a heavy Confederate artillery fire was directed against Fort Gray. Both Fort Gray and Battery Worth in Plymouth returned the fire. Soon a Union gunboat, the Bombshell, was disabled by the Confederate barrage. At 6:30 P.M. on the 18th the Confederates advanced their line and began an infantry assault upon the Union position; but this attack was abandoned at 8 P.M. The 85th Redoubt was then attacked and captured at 11 P.M. At 3 A.M. on April 19, the Confederates again attacked Fort Gray. Soon the Confederate iron-clad ram Albemarle, aiding the army, passed undetected down the river. The Albemarle engaged the Southfield and the Miami at 3:30 A.M., sinking the former and driving the latter away. The Albemarle then began to shell the Union defenses. |

African Americans Defend Washington Prior to formation of 1st N.C. Colored Volunteers about 100 black men were armed to aid Union forces during the siege of Washington in 1863.During the siege of Washington in April 1863, Union troops armed African Americans to participate in the defense of the town. The incident is an early example in North Carolina of the shift in U.S. policy towards recruiting African Americans for military service in the Civil War. At the beginning of the war, the United States did not recruit African Americans for military service. Although President Abraham Lincoln had long detested slavery, he felt not only bound by slavery's Constitutional protections but also wished to keep the slaveholding states of Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland within the Union. Lincoln's initial war plans were thus based on restoring the Union, not emancipation. This policy gradually succumbed to the realities of war. The escape of slaves into Union lines led some military commanders to forbid their return to their owners in order to hamper the Confederate war effort. Some Union commanders put escaped slaves to various types of military labor, while others utilized slaves and free blacks as spies and scouts. In the meantime, black and white abolitionists strenuously advocated the recruitment of African Americans as soldiers to provide an opportunity to show the government and the Northern public that emancipation was worthy of support, and to allow African Americans an opportunity to strike a direct blow against slavery by defeating the Confederacy. These developments led to a shift in Lincoln's policy. In September 1862, he issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The idea of recruiting African American as soldiers now took on a new life. By early 1863, the first African American regiments were beginning to organize. Following the arrival of Federal forces in eastern North Carolina in early 1862, thousands of escaped slaves made their way to the coastal zone controlled by Union troops. Efforts to organize African Americans in the area were initially scattered, and reflected the uncertainties of early Union policy. Immediate manpower necessities were often the cause. Federal troops occupying Elizabeth City armed African Americans to act as pickets as early as October 1862. The siege of Washington provided another practical opportunity to implement the new policy, as the need to provide additional strength for the garrison led to the arming of African Americans. A postwar history of the 44th Regiment Massachusetts Infantry credited Col. Francis L. Lee of that regiment with arming the African Americans at Washington, sometime after his unit arrived on March 16. A postwar history of the 27th Regiment Massachusetts Infantry implied that the men were armed on or about March 30, the first day of the siege. Department of North Carolina commander Maj. Gen. John G. Foster arrived at Washington early in the morning of the same day to take charge of the defense, so there is room for doubt as to whether Lee took the initiative or acted under Foster's orders. Although Foster made no mention of arming African Americans at Washington in his April 30 campaign report, he did so in a May 4 letter to U.S. secretary of war Edwin M. Stanton. However, he credited the initial idea to the African Americans themselves: "During the late attack on Washington, the negroes applied to me for arms, and to strengthen my lines I armed about 120, all that I had arms for." The April 13, 1863 entry of a wartime diary by a member of the 44th Massachusetts indicated that 100 African Americans were among the town's defenders by that date. This figure, and Foster's slightly larger estimate of "about 120," should be considered approximate. Although the siege of Washington does not mark the first attempt in North Carolina to arm African Americans to fight against the Confederacy, it is nevertheless one of several important early steps towards the formal organization of African Americans for military service in the state, and deserves to be remembered on those grounds. |

St. John The Evangelist Church The first Roman Catholic church in North Carolina. Consecrated, 1829. Burned by Federal troops, 1864.Bishop England, who had organized the parish in 1821, consecrated St. John the Evangelist Church, on March 25, 1829. The building served the local Catholic population until April 1864, when it was burned, along with much of Washington, by evacuating Union troops. The fire also caused much damage to grave markers in the Catholic cemetery. For over sixty years thereafter the town had no Catholic church and worship was held in private homes. The original site today is the site of the First Methodist Church of Washington. |

After the Civil War, women's associations throughout the South sought to gather the Confederate dead from battlefield burial sites and reinter the remains in proper cemeteries, while Confederate monuments were erected in courthouse squares and other public places. A monument titled "To Our Confederate Dead" was unveiled on Confederate Memorial Day, May 10, 1888, at Washington's Monument Park (then located at the corner of Water and Monumental Streets). Exactly ten years later, the memorial was relocated to Oakdale Cemetery. The monument was dedicated to "The Private Soldier" and modeled after Capt. Thomas M. Allen, Co. E, (Southern Guards), 4th North Carolina Infantry. Allen, captured at Gettysburg, Pa., in July 1863, was among 600 officers transferred from Fort Delaware to Morris Island, S.C., in August 1864, to be confined in front of the Union batteries during the siege of Charleston. Allen and most of the offices eventually were returned to Fort Delaware and released after the war, becoming known as the "Immortal 600."

On January 17, 1897, here in Oakdale Cemetery, the Ladies Memorial Association of Beaufort County reburied 17 Confederates killed during the September 6, 1862, Battle of Washington. The Children of the Confederacy dedicated the monument at the cemetery's southwest entrance on May 10, 1905. On May 10, 1975, the Confederate cannon was placed in memory of Edmond Hoyt Harding by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The Pamlico Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy has conducted annual Memorial Day celebrations from 1883 to the present. The old veterans marched from Washington to the monument until the last one, J.D. Paul, died in 1938.

Captions:

(Left) Wilson T. Farrow served in Co. H, 33rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment as 1st Lt. He is buried in Oakdale Cemetery.

(Right) Reverend Nathaniel Harding enlisted on August 20, 1864, at age 17 as a private in Co. I, 67th Regiment N.C. Troops, also known as Co. I, Whitford's Battalion N.C., Partisan Rangers. According to his family, while serving near Plymouth, N.C., he fell in a creek while weighted down with equipment and was pulled to safety by a Union officer who took him under his wing. After the war, Harding was educated at the Episcopal Academy, Cheshire, Conn., and Trinity College, Hartford, Conn. He became a deacon in 1873 and a priest in 1875. From 1873 until his death in 1917, he spent his ministry a St. Peter's Episcopal Church here in Washington. He is buried in Oakdale Cemetery.

https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p15012coll8/id/10868

This monument was dedicated May 10, 1872 to perpetuate deeds of the brave and in grateful tribute to the memory of 550 honored unknown confederate dead at the battle of Fort Fisher who lie buried here.

Erected May 10, 1905 by Washington Gray Chapter Children of the Confederacy, organized in 1897 by Margaret Arthur Call. To the memory of 17 soldiers killed in defense of Washington Sept. 6, 1862.

| Battles in Washington NC: |

|---|

| https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/northcarolina.htm |

March 20-21, 1862 Expedition to Washington:Massachusetts 24th Infantry United States - Gunboats "Delaware," "Louisiana" and "Commodore Barney" |

June 24, 1862 Reconnoissance from Washington to Tranter's Creek:New York - 3d Cavalry (Co. "I") |

Sept. 6, 1862 Action, Washington:Massachusetts - 24th Infantry New York - 3d Cavalry; Batteries "G" and "H," 3d Light Arty North Carolina - 1st Infantry Union loss, 9 killed, 42 wounded, 4 missing. Total: 55 |

Feb. 13, 1863 Skirmish near Washington:Massachusetts - -27th Infantry (Detachment) New York - 3d Cavalry (Detachment) |

March 30-April 20, 1863 Siege of Washington:Massachusetts - 27th (8 Cos.) and 44th (8 Cos.) Infantry New York - 3d Cavalry (1 Co.); Battery "G," 3d Light Arty North Carolina - 1st Infantry (2 Cos.) Union loss, 1 killed, 24 wounded. Total: 25 |

March 30, 1863 Skirmish, Washington:Massachusetts - 44th Infantry (Cos. "A" and "G") New York - 3d Cavalry (Detachment) |

April 3, 1863 Skirmish, Washington:Massachusetts - 44th Infantry |

April 7-10, 1863 Expedition from Newberne for relief of Washington:Massachusetts - 3d, 5th, 8th, 17th, 43d and 44th (2 Co's) Infantry New York - Battery "H" 3d Light Arty.; 85th, 96th, 132d and 158th Infantry Pennsylvania - 101st, 103d, 158th, 171st and 175th Infantry Rhode Island - 5th Heavy Arty, Battery "F" 1st Light Arty |

April 15, 1863 Skirmish, Washington:Massachusetts - 44th Infantry |

April 17-19 Expedition from Newberne to Washington:Massachusetts - 17th and 23d Infantry New York 3d Cavalry (Detachment) Rhode Island -Battery "F" 1st Light Arty |

Aug. 14, 1863 Skirmish, Washington:New York - 12th Cavalry |

Dec. 17, 1863 Expedition from Washington to Chicoa Creek:Pennsylvania - 58th Infantry (Detachment) North Carolina - 1st Infantry (Detachment) |

April 27-28, 1864 Skirmishes, Washington:Massachusetts - 17th Infantry New York - 23d Indpt. Battery Light Arty |