Pebble Pups is a science club that provides educational fun for kids to learn about earth science through engaging activities, projects, field trips and presentations.

Pebble Pups meet monthly, and is open to the children of OGMS members. It is a great way to spend time with your kids while they learn amazing and enriching things about our world.

A less frequent occurrence is for plumes to form in the agate. Carnelian agate is an ancient gemstone that was greatly appreciated by ancient peoples. Though Carnelian agate is much less expensive today than it was in ancient times, it is still a stone that is cherished and appreciated.

The carnelian agate before you came from two chunks of rock collected in central Oregon. Obviously it is the plumes that make this carnelian agate exceptional. From plumes that are wispy, delicate and ephemeral to those that are bold and dramatic., it is the plumes that draw us into this stone. These 15 cabochons reveal an uncommon and beautiful aspect to this stone that was greatly prized by the ancients and still attracts and delights us today.

A True California Gem

One of my favorite California gemstones is Nipomo Marcasite. Nipomo is located on the California coast north of Santa Mario and south of Arroyo Grande. It found on ranch land in the Nipomo area. At one time the owners of the land on which the stone is found gave permission to collectors to come on to the property and dig for the stone. Unfortunately, a few disrespectful collectors abused the privilege by ignoring the owner's wishes by crossing fences, walking through planted fields, closing or not closing gates. One rumor has it that one collector even used dynamite without permission. Whatever the case. the property was close to collecting in the 1960s just before I got interested and involved in collecting and working with gemstones.

Shortly after I joined a gem club in the late 1960s. I had a conversation with a senior member of the club who was somewhat of a mentor to me as someone new to the hobby. In this conversation, I bemoaned the fact that I never got a chance to dig and collect Nipomo Marcasite because it was closed to collecting before I became involved. I remember this elderly gentleman with a slight smile on his face telling me to come by his house the next day because he might have something for me. At his home the next day he gave me a boulder of Nipomo Marcasite weighing over a hundred pounds. His only requirement was that I do something with the rock. Over the years, I have fulfilled his requests. This case of stones is just one example.

Nipamo Marcasite is composed of iron pyrite io an agale matrix. These are Two very different matenals. On the MOH hardness scale, iron pyrite registers a 5, The agate matrix registers a 7 the Mah hardness scale. Because the iron pyrite is considerably softer than the agate, one would expect the iron pyrife to under cut and leave a lumpy surface when polished. The beauty of this gemstone is that it takes a smooth and brilliant polish. There is no unevenness evident at all in the polishing process.

Not only did my friend give me a large quantity of Nipomo Marcasite, but the quality of the stone is also top notch. The balance between agate and iron pyrite is optimum. Some of the agate has crystal cavities while some displays fortification. There is also what I call marcasite flowers, which are round bursts of marcasite surrounded by agate. Several of the cabs brilliantly display the quality. The quality is evident in the 22 cabochons I have chosen to display. One of the drawbacks in working with this stone is that it is extremely dirty. When ground and sanded the iron pyrite turns the water used in the process black which in turm stains one's hands and anything else it gets on to. It is in general a pain, but as you can see definitely worth the effort and inconvenience. Enjoy!

What do you see?

When the pandemic struck and we were all stuck at home, I decided to see hows many lapidary and jewelry projects might be crafted using materials sourced locally from beaches in my own backyard of Ventura County while waiting for the VC Fair to ride again.

During weekly walks with my faithful dog, I found much to work with in conjunction with commercial cab mounts, jump rings, and pinch balls. I hope you enjoy the results! Don't wait for the next pandemic. Explore your backyard today. Who knows what treasures await?

Composed of yellow Calcite and brown Aragonite in a gray calcarcous mudstone. This lapidary material is a favorite of rockhounds as it is easy to cut, carve, and polish into various forms.

30-50 Million Years Old

Named after the majestic Condors that fly over the Andes Mountains

San Simeon California

Surfers, Surfboards, Waves

San Louis Obispo California

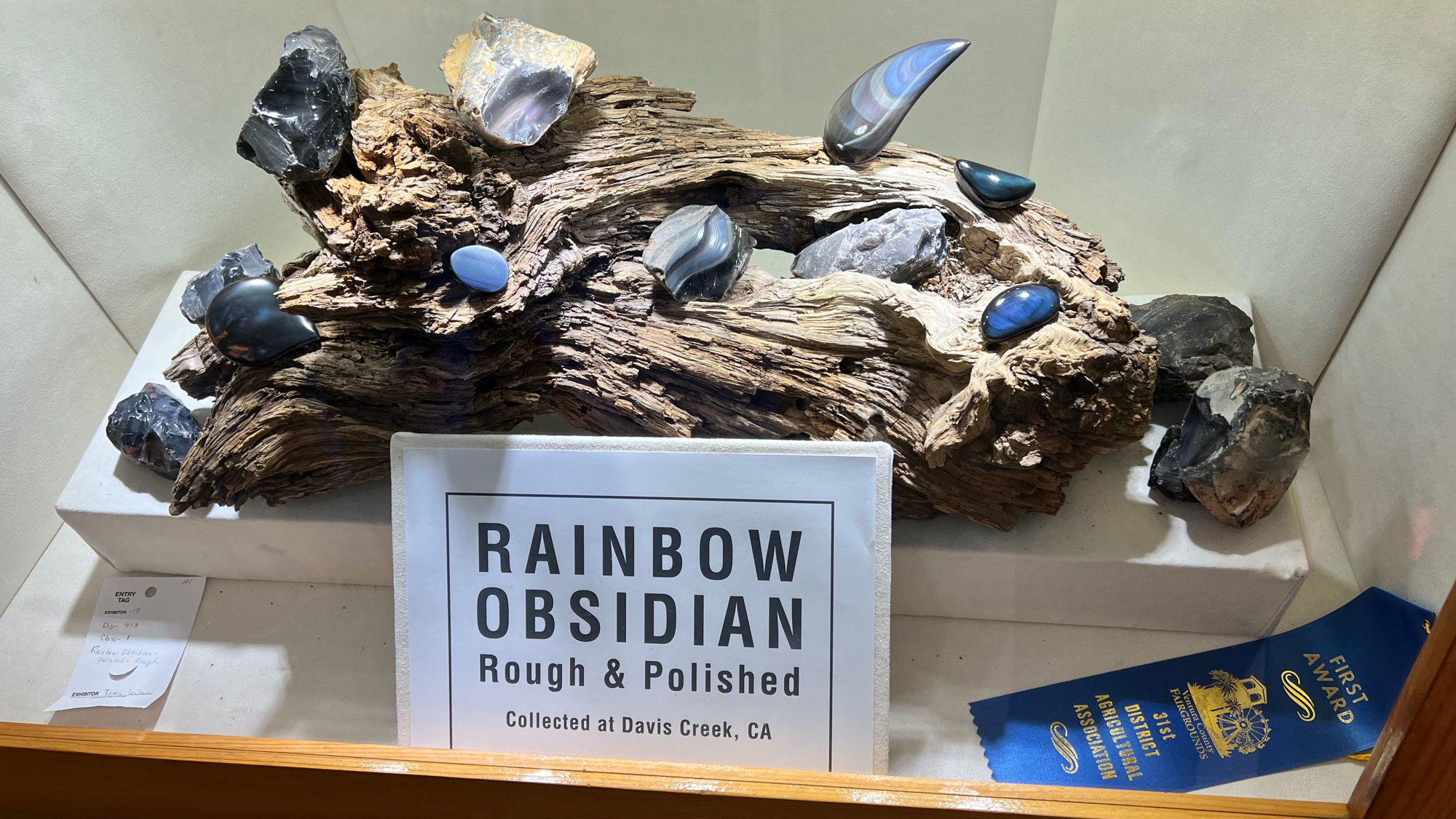

Rough & Polished

For its size, Scotland boasts a wonderful assortment of agates, or "Scotch pebbles" as they were once called. While quantity is limited and size is often small, the beauty and variety is equal to anywhere in the world. How did such agates come to be? Thanks to plate tectonics and continental drift, Scotland has traversed the globe the past half billion years.

Beginning near the South Pole, it has slid north and has seen oceans open and close and open again as oceanic and continental plates subducted beneath one another, separated, or smashed together. At one time, Scotland was in the middle of a desert covering a huge supercontinent; at another time, it was more North American than European.

Thanks to plates rifting and colliding, Scotland saw outpourings of lava at least four times in the past 500 million years. Two outpourings were responsible for most agates now found there. These agates formed in pockets left by gas bubbles as basaltic or andesitic lavas cooled. The oldest (380 million years) are "the Old Red Sandstone lavas" of the Devonian Period found within the Midland valley and along the North Sea coast, from Montrose in the northeast to Maidens in the southwest. Pockets also are found in the Cheviot Hills on the southeastern border and at Oban in the southwest Highlands. The youngest volcanic rocks (50-65 million years old) are "Tertiary lavas" found along the Atlantic side of Scotland. These make up much of the isles of Skye, Mull, and Rüm.

Scotch Pebble Jewelry

A Once Proud Cottage Industry

The heyday of collecting and working with Scottish agates was the Victorian period of 1837-1901. Agates were referred to as "pebbles" in Scotland, and so-called "Scotch pebble jewellery," crafted from such agates, was popularized by Queen Victoria.

Such jewelry typically consists of brooches with multi-colored agates and jaspers flat-lapped, polished, and set in sterling silver and sometimes embellished with a faceted stone of cairngorm (a brown-orange variety of smoky quartz). In addition to brooches, a lapidarist might also have crafted hat pins, kilt pins, and the like. All "pebbles" used were locally sourced.

Because Scottish agates were never plentiful, this was a small-scale operation with only some 200 "professional lapidarists" at the peak of operations in the late 1800s. Because Scottish agates were typically small, most stones set in jewelry were sliced thin and small.

One of the last professional lapidarists, Alexander Begbie, died March 7, 1958. He had attracted a devoted group of 30 followers in the city of Edinburgh led by Ron Bennet to whom he left his skills and knowledge of the craft and his equipment. Thus began the Scottish Mineral & Lapidary Club, the oldest continuously operating amateur gem and mineral society in all of the United Kingdom devoted to the lapidary arts. Its members still are devoted to continuing a once proud cottage industry!

Panamint Valley California

Microcrystalline quartz in the variety of Blue Chalcedony is found in the Argus Range of Panamint Valley. The shades of Blue Chalcedony range from dark bluish green to pale bluish gray. The rock surrounding the Blue Chalcedony is tan to brown Jasper. Specimens in thls exhibit shows how the Blue Chalcedony was injected and forced into the rock, thus ripping it apart and filling in the fractures.

During the Injection process the hot, molten quartz-rich fluids formed into banded layers and settled in beautiful swirling patterns that are seen in the polished slabs and cabochons. The original parent rock was metamorphosed into Jasper when the hot, quartz-rich fluids were injected.

My exhibit shows the various forms of Blue Chalcedony from finely polished slabs, cabochons, polished stones and native specimens.

Juab County Utah

Ventura Gem & Mineral Society

PeridotEllie L., Pebble Pup

Peridot is a green gemstone, otherwise known as the gem of spring' even though it's a summer birthstone, the birthstone of August. It can be found around the world and is a very popular gem. It only comes in an olive green color. Peridot was found on the comet called Temple 1. I love Peridot because I love the color green.

- Obsidian Blade

- Antler Handle

- Cap Plume Agate

- Stand Silver Lace Onyx

Silver Lake Onyx

Knapped Eagles and Bears

Michigan's Petoskey Stone is actually a 350-million-year-old fossil coral Hexagonaria percarinata. It has a honeycomb pattern with radiating lines reminiscent of sunbeams. It is soft and polishes easily and is used to make carvings for tourist knickknacks, like this toadstool. You can collect coral "heads" at various spots in Michigan, or you can find water-worn cobbles on Lake Michigan beaches around Carlevoix and Petoskey.

"Petoskey" comes from an Ottawa Indian chief. Sunbeams fell upon his newborn face, so he was named Pe-tos-e-gay ("rising sun" or "sunbeams of promise"). Settlers named a new town in his honor with the English spelling of Petoskey. His granddaughter Ella Jane Petoskey got to see Petoskey Stone declared the Michigan State Stone in 1965.