October 1944, as Allied forces fought to expel the Nazis from France, the 442nd unit of Japanese American soldiers were sent into the harsh terrain of the Vosges mountains of northeastern France - a region not breached by militarily since the Roman Empire. They were ordered to extract a Texas National Guard unit trapped deep in the forest, surrounded by 6,000 Nazi troops. The Battle of the Lost Battalion has been hailed as one of the fiercest and most heroic ground battles in American military history. There were so many dead people on the road that they had to bring a bulldozer to push them off the road. Between October 14 and October 31 the 442nd suffered more than 800 casualties.

Karate Kid Movies

Mr. Miyagi was a World War II veteran who had fought in the 442nd.

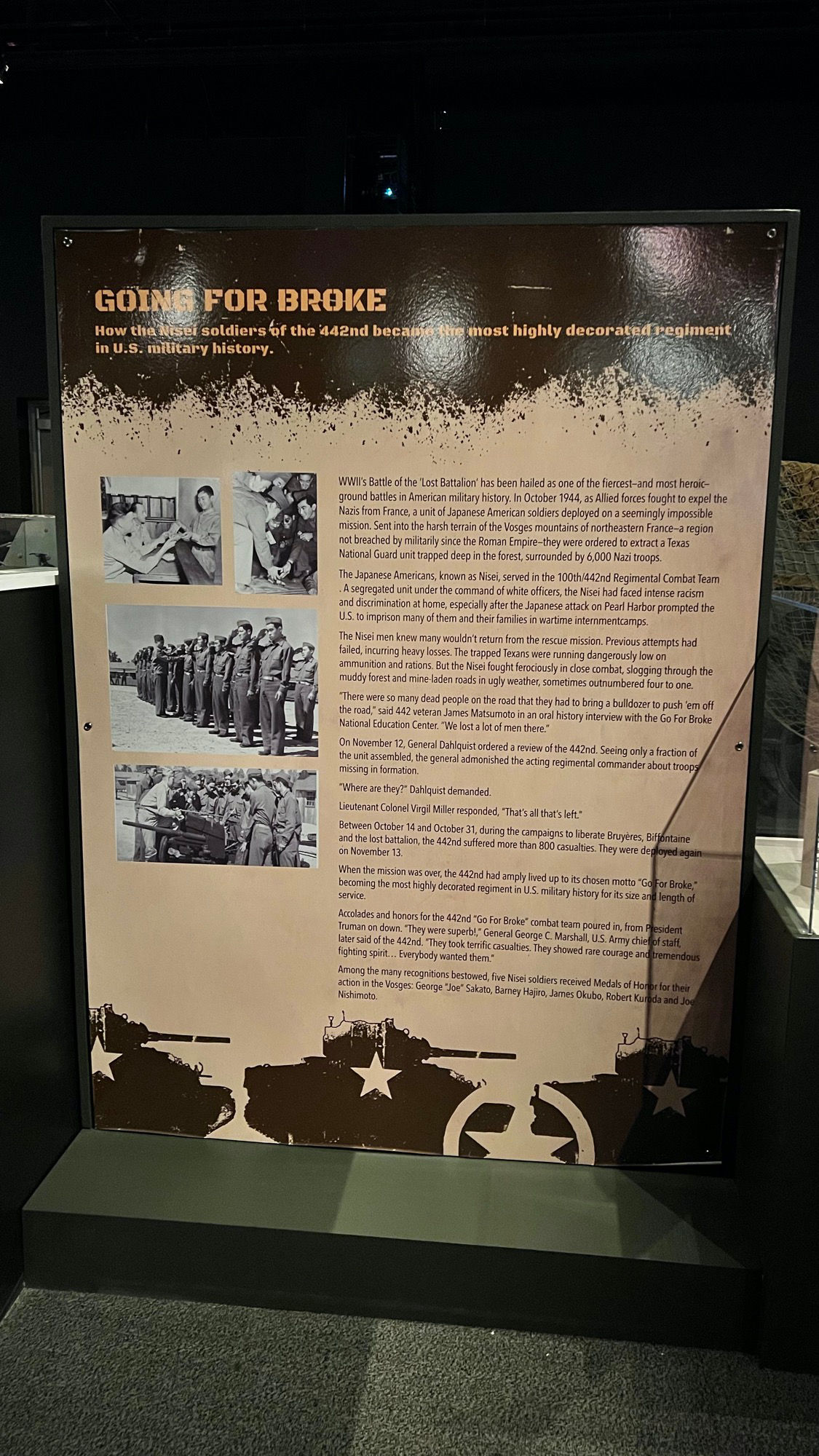

How the Nisei soldiers of the 442nd became the most highly decorated regiment in U.S. military history

WWII's Battle of the 'Lost Battalion' has been hailed as one of the fiercest - and most heroic - ground battles in American military history. In October 1944, as Allied forces fought to expel the Nazis from France, a unit of Japanese American soldiers deployed on a seemingly impossible mission. Sent into the harsh terrain of the Vosges mountains of northeastern France - a region not breached by militarily since the Roman Empire - they were ordered to extract a Texas National Guard unit trapped deep in the forest, surrounded by 6,000 Nazi troops.

The Japanese Americans, known as Nisei, served in the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team. A segregated unit under the command of white officers, the Nisei had faced intense racism and discrimination at home, especially after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor prompted the U.S. to imprison many of them and their families in wartime internment camps.

The Nisei men knew many wouldn't return from the rescue mission. Previous attempts had failed, incurring heavy losses. The trapped Texans were running dangerously low on ammunition and rations. But the Nisei fought ferociously in close combat, slogging through the muddy forest and mine-laden roads in ugly weather, sometimes outnumbered four to one.

There were so many dead people on the road that they had to bring a bulldozer to push 'em off the road," said 442 veteran James Matsumoto in an oral history interview with the Go For Broke National Education Center. "We lost a lot of men there."

On November 12, General Dahlquist ordered a review of the 442nd.

Seeing only a fraction of the unit assembled, the general admonished the acting regimental commander about troops missing in formation.

"Where are they?" Dahlguist demanded.

Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Miller responded, "That's all that's left."

On November 12, General Dahlquist ordered a review of the 442nd.

Seeing only a fraction of the unit assembled, the general admonished the acting regimental commander about troops missing in formation.

"Where are they?" Dahlguist demanded.

Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Miller responded, "That's all that's left."

Between October 14 and October 31, during the campaigns to liberate Bruyeres, Biffontaine and the lost battalion, the 442nd suffered more than 800 casualties. They were deployed again on November 13. When the mission was over, the 442nd had amply lived up to its chosen motto "Go For Broke," becoming the most highly decorated regiment in U.S. military history for its size and length of service.

Accolades and honors for the 442nd "Go For Broke" combat team poured in, from President Truman on down. "They were superb!," General George C. Marshall, US. Army chief of staff, later said of the 442nd. "They took terrific casualties. They showed rare courage and tremendous fighting spirit... Everybody wanted them."

Among the many recognitions bestowed, five Nisei soldiers received Medals of Honor for their action in the Vosges: George "Joe" Sakato, Barney Hajiro, James Okubo, Robert Kuroda, and Joe Nishimoto.

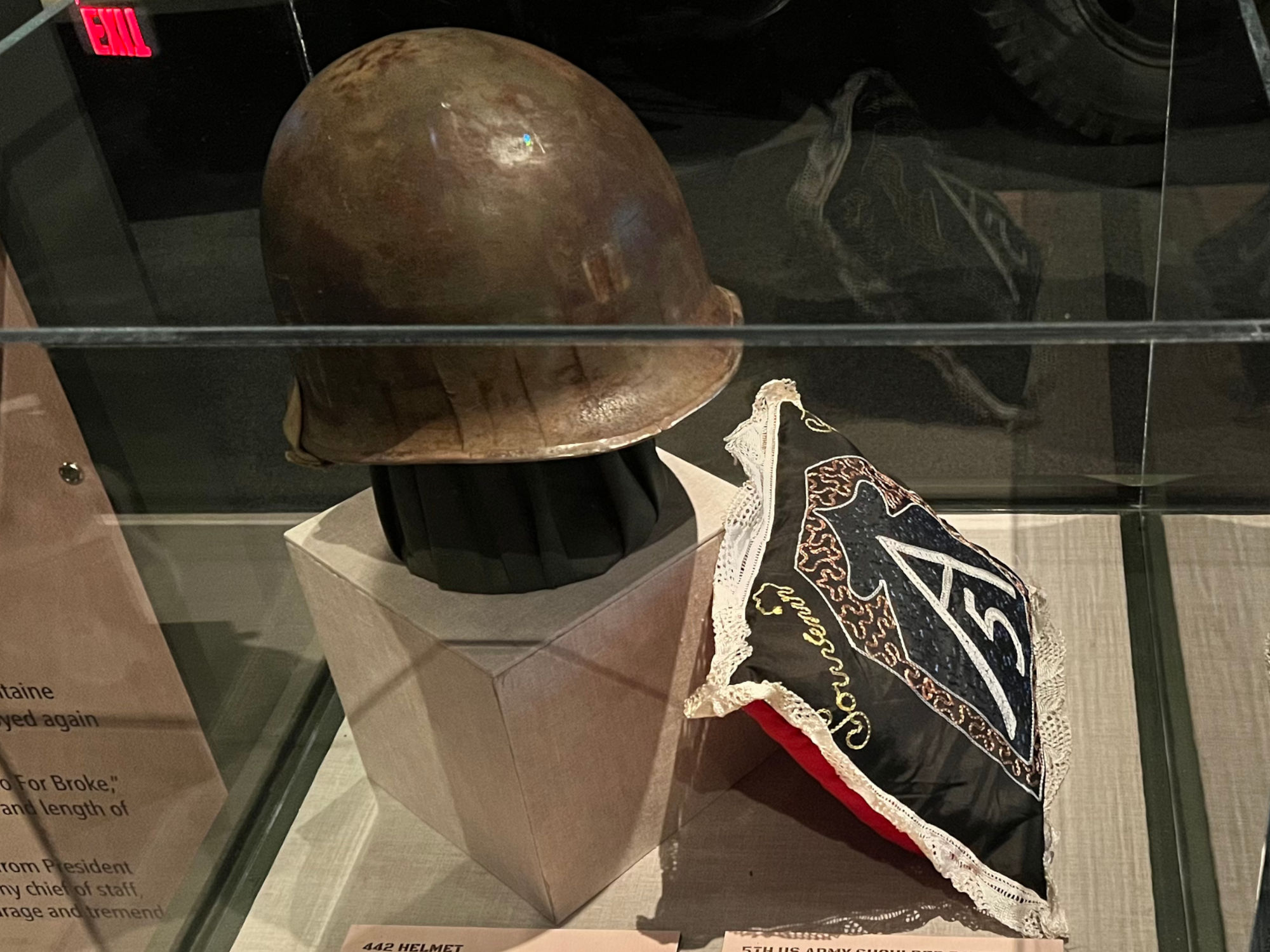

- 442nd Helmet

1944-1946

This helmet was worn by a member of the Japanese American 442nd Infantry Regiment. It is painted with their patch, the hand of the Statue of Liberty holding aloft her torch, in red, white, and blue. - 5th US Army Shoulder Patch Pillowcase

1944

This pillow sham is embroidered with the 5th US Army shoulder patch design, likely purchased as a souvenir in Italy. The 100th Battalion/442nd Infantry Regiment was attached to the 5th Army, and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) fought against German forces in the mountains of Northern Italy.

How a Japanese American Regiment Rescued WWII's ‘Lost Battalion'

The Nisei soldiers of the 442nd became the most highly decorated regiment in U.S. military history for its size and length of service.History.comWWII's Battle of the ‘Lost Battalion' has been hailed as one of the fiercest-and most heroic-ground battles in American military history. In October 1944, as Allied forces fought to expel the Nazis from France, a unit of Japanese American soldiers deployed on a seemingly impossible mission. Sent into the harsh terrain of the Vosges mountains of northeastern France-a region not breached militarily since the Roman Empire-they were ordered to extract a Texas National Guard unit trapped deep in the forest, surrounded by 6,000 Nazi troops.The Japanese Americans, known as Nisei, served in the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team (442nd). A segregated unit under the command of white officers, the Nisei had faced intense racism and discrimination at home, especially after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor prompted the U.S. to imprison many of them and their families in wartime incarceration camps. During their French campaign, the 442nd included the 100th Infantry Battalion (a mostly Nisei unit from Hawai'i that had its own storied history before merging with the 442nd), the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion and the 232nd Engineer Company-all of which played crucial roles.

The Nisei men knew many wouldn't return from the rescue mission. Previous attempts had failed, incurring heavy losses. The trapped Texans were running dangerously low on ammunition and rations. But the Nisei fought ferociously in close combat, slogging through the muddy forest and mine-laden roads in ugly weather, sometimes outnumbered four to one. When the mission was over, the 442nd had amply lived up to its chosen motto "Go For Broke," becoming the most highly decorated regiment in U.S. military history for its size and length of service.

Timeline of the ‘Lost Battalion' Rescue

- October 26: Originally, General Dahlquist ordered the Nisei, on just two days rest, to make a frontal attack on the hill where the Texans were stranded. But his officers argued that such a maneuver would incur high losses, proposing instead that they outflank the Nazis.

- October 27: Nisei soldiers mobilized on both sides of the ridgeline road north of Biffontaine. German landmines, thick underbrush, dense forest and a persistent defense slowed the Nisei advance.

- October 28: Under heavy artillery and mortar fire-and growing casualties-they advanced to within 1,500 yards of the Texans.

- October 29: The Nisei battalion command received a radio message that the Texans' situation had become desperate. A platoon of tanks arrived, providing support fire from its 75-mm cannons, but it fell to the Nisei infantrymen to continue alone up the steep bluff teeming with Nazis, later dubbed "Suicide Hill."

After an order to "fix" bayonets, men from "I" and "K" Companies rose, firing from the hip, advancing as one, led by their commanding officer. According to Pfc. Ichigi Kashiwagi, of K Company, "We yelled our heads off and shot the head off everything that moved... We didn't care anymore."

At the sight of this action, the Germans, who had just engaged in a fierce 30-minute firefight, threw up their arms and fled their positions.

About the same time, 3,000 yards to the rear, the "E" and "F" companies used a pincer movement to outflank the Nazis as planned and attack from behind, while "G" company advanced frontally, catching the enemy by surprise. The coordinated action annihilated the Germans.

- October 30: "I" Company made first contact with the lost battalion. The radio message from the Texans said: "Patrol from 442nd here. Tell them that we love them!" Approximately 211 soldiers of the lost battalion's original 275 survived the siege.

After less than two days in reserve, the 442nd was ordered to attempt the rescue of the "Lost Battalion" two miles east of Biffontaine. On 23 October Colonel Lundquist's 141st Regiment, soon to be known as the "Alamo" Regiment, began its attack on the German line that ran from Rambervillers to Biffontaine. Tuesday morning, 24 October, the left flank of the 141st, commanded by Technical Sergeant Charles H. Coolidge, ran into heavy action, fending off numerous German attacks throughout the days of 25 and 26 October. The right flank command post was overrun and 275 men of Lieutenant Colonel William Bird's 1st Battalion Companies A, B, C, and a platoon from Company D were cut off 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) behind enemy lines. The "Lost Battalion" was cut off by German troops and was forced to dig in until help arrived. It was nearly a week before they saw friendly soldiers.At 4 a.m. on Friday 27 October, General John E. Dahlquist ordered the 442nd to move out and rescue the cut-off battalion. The 442nd had the support of the 522nd and 133rd Field Artillery units but at first made little headway against German General Richter's infantry and artillery front line. For the next few days the 442nd engaged in the heaviest fighting it had seen in the war, as the elements combined with the Germans to slow their advance. Dense fog and very dark nights prevented the men from seeing even twenty feet. Many men had to hang onto the man in front of him just to know where to go. Rainfall, snow, cold, mud, fatigue, trench foot, and even exploding trees plagued them as they moved deeper into the Vosges and closer to the German frontlines. The 141st continued fighting-in all directions.

SSgt. Jack WilsonWhen we realized we were cut off, we dug a circle at the top of the ridge. I had two heavy, water-cooled machine guns with us at this time, and about nine or ten men to handle them. I put one gun on the right front with about half of my men, and the other gun to the left. We cut down small trees to cover our holes and then piled as much dirt on top as we could. We were real low on supplies, so we pooled all of our food.

Airdrops with ammo and food for the 141st were called off by dense fog or landed in German hands. Many Germans did not know that they had cut off an American unit. "We didn't know that we had surrounded the Americans until they were being supplied by air. One of the supply containers, dropped by parachute, landed near us. The packages were divided up amongst us." Only on 29 October was the 442nd told why they were being forced to attack the German front lines so intensely.

The fighting was intense for the Germans as well. Gebirgsjager Battalion 202 from Salzburg was cut off from Gebirgsjager Battalion 201 from Garmisch. Both sides eventually rescued their cut-off battalions.

As the men of the 442nd went deeper and deeper they became more hesitant, until reaching the point where they would not move from behind a tree or come out of a foxhole. However, this all changed in an instant. The men of Companies I and K of 3rd Battalion had their backs against the wall, but as each one saw another rise to attack, then another also rose. Then every Nisei charged the Germans screaming, and many screaming "Banzai!": 83 Through gunfire, artillery shells, and fragments from trees, and Nisei going down one after another, they charged.

Colonel Rolin's grenadiers put up a desperate fight, but nothing could stop the Nisei rushing up the steep slopes, shouting, firing from the hip, and lobbing hand grenades into dugouts. Finally the German defenses broke and the surviving grenadiers fled in disarray. That afternoon the American aid stations were crowded with casualties. The 2nd platoon of Company I had only two men left, and the 1st platoon was down to twenty." On the afternoon of 30 October, 3rd Battalion broke through and reached the 141st, rescuing 211 T-Patchers at the cost of 800 men in five days. However, the fighting continued for the 442nd as they moved past the 141st. The drive continued until they reached Saint-Die on 17 November when they were finally pulled back. The 100th fielded 1,432 men a year earlier, but was now down to 239 infantrymen and 21 officers. Second Battalion was down to 316 riflemen and 17 officers, while not a single company in 3rd Battalion had over 100 riflemen; the entire 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team was down to less than 800 soldiers. Earlier (on 13 October) when attached to the 36th Infantry, the unit was at 2,943 riflemen and officers, thus in only three weeks 140 were killed and a further 1,800 had been wounded, while 43 were missing.

WIKIPEDIAThe United States Army 442nd Infantry Regiment

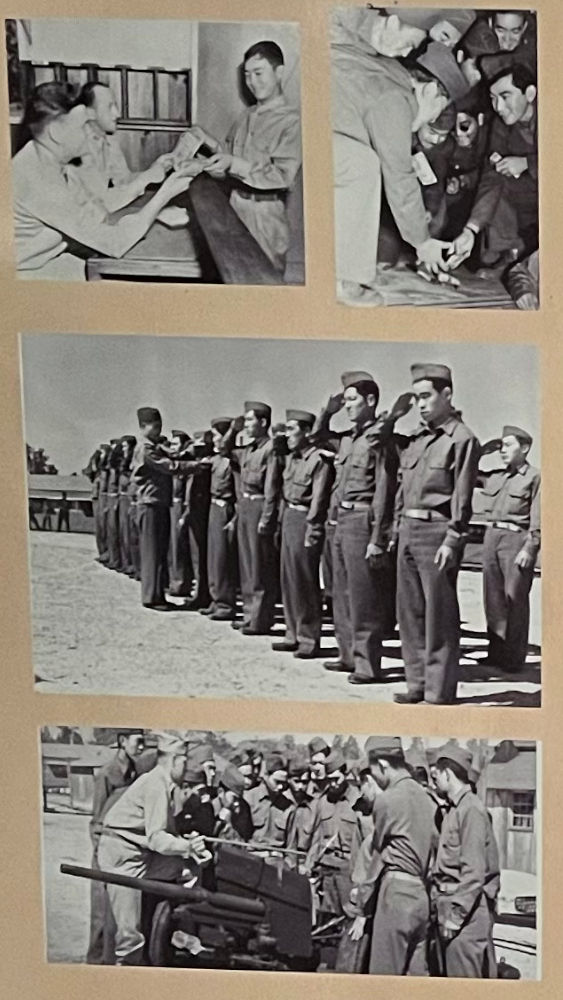

The regiment is best known as the most decorated in U.S. military history and as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-generation American soldiers of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who fought in World War II.Beginning in 1944, the regiment fought primarily in the European Theatre, in particular Italy, southern France, and Germany. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) was organized on March 23, 1943, in response to the War Department's call for volunteers to form the segregated Japanese American army combat unit. More than 12,000 Nisei (second-generation Japanese American) volunteers answered the call. Ultimately 2,686 from Hawaii and 1,500 from mainland U.S. internment camps assembled at Camp Shelby, Mississippi in April 1943 for a year of infantry training. Many of the soldiers from the continental U.S. had families in internment camps while they fought abroad.

442nd's Motto: "Go for Broke"The 442nd Regiment is the most decorated unit in U.S. military history.

Created as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team when it was activated 1 February 1943, the unit quickly grew to its fighting complement of about 4,000 men by April 1943, and an eventual total of about 10,000 men served in the combined 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd RCT. The combined units earned, in less than two years

- More than 4,000 Purple Hearts

- 4,000 Bronze Star Medals

- Seven Presidential Unit Citations

- Twenty-one of its members were awarded the Medal of Honor

In 2010, Congress approved the granting of the Congressional Gold Medal to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and associated units who served during World War II, and in 2012, all surviving members were made chevaliers of the French Legion d'Honneur for their actions contributing to the liberation of France and their heroic rescue of the Lost Battalion.m

The 442nd RCT was inactivated in 1946 and reactivated as a reserve battalion in 1947, garrisoned at Fort Shafter, Hawaii. The 442nd lives on through the 100th Battalion/442nd Infantry Regiment, and is the only current infantry formation in the Army Reserve.

Background

Most Japanese Americans who fought in World War II were Nisei, born in the United States to immigrant parents. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy's attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Japanese-American men were initially categorized as 4C (enemy alien) and therefore not subject to the draft. On 19 February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War

EO 9066to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.Although the order did not refer specifically to people of Japanese ancestry, it was targeted largely for the internment of people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. In March 1942, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, issued the first of 108 military proclamations that resulted in the forced relocation from their residences to guarded concentration camps of more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast, the great majority of the ethnic community. Two-thirds were born in the United States.

In Hawaii, the military imposed martial law, complete with curfews and blackouts. As a large portion of the population was of Japanese ancestry (150,000 out of 400,000 people in 1937), internment was deemed not practical; it was strongly opposed by the island's business community, which was heavily dependent on the labor force of those of Japanese ancestry (this contrasts with the business communities on the mainland that competed with Japanese American businesses, and which exploited the opportunity to buy up Japanese American properties that had to be surrendered). It was accurately believed that an internment of Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants in Hawaii would have had catastrophic results for the Hawaiian economy; intelligence reports at the time noted that "the Japanese, through a concentration of effort in select industries, had achieved essential roles in several key sectors of the economy in Hawaii." In addition, other reports indicated that those of Japanese descent in Hawaii "had access to virtually all jobs in the economy, including high-status, high-paying jobs (e.g., professional and managerial jobs)," suggesting that a mass internment of people of Japanese descent in Hawaii would have negatively impacted every sector of the Hawaiian economy.

When the War Department called for the removal of all soldiers of Japanese ancestry from active service in early 1942, General Delos C. Emmons, commander of the U.S. Army in Hawaii, decided to discharge those in the Hawaii Territorial Guard, which was composed mainly of ROTC students from the University of Hawaii. However, he permitted the more than 1,300 Japanese-American soldiers of the 298th and 299th Infantry Regiment regiments of the Hawaii National Guard to remain in service. The discharged members of the Hawaii Territorial Guard petitioned General Emmons to allow them to assist in the war effort. The petition was granted and they formed a group called the Varsity Victory Volunteers, which performed various military construction jobs. General Emmons, worried about the loyalty of Japanese-American soldiers in the event of a Japanese invasion, recommended to the War Department that those in the 298th and 299th regiments be organized into a "Hawaiian Provisional Battalion" and sent to the mainland. The move was authorized, and on 5 June 1942, the Hawaiian Provisional Battalion set sail for training. They landed at Oakland, California on 10 June 1942 and two days later were sent to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. On 15 June 1942, the battalion was designated the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate)-the "One Puka Puka".

Mainly because of the actions of the 100th and the Varsity Victory Volunteers, the War Department directed that a Japanese-American Combat Team should be activated comprising the 442d Infantry Regiment, the 522d Field Artillery Battalion, and the 232d Engineer Combat Company.

The order dated 22 January 1943, directed, "All cadre men must be American citizens of Japanese ancestry who have resided in the United States since birth" and "Officers of field grade and captains furnished under the provisions of subparagraphs a, b and c above, will be white American citizens. Other officers will be of Japanese ancestry insofar as practicable."

In accordance with those orders, the 442d Combat Team was activated 1 February 1943, by General Orders, Headquarters Third Army. Colonel Charles W. Pence took command, with Lieutenant Colonel Merritt B. Booth as executive officer. Lieutenant Colonel Keith K. Tatom commanded the 1st Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel James M. Hanley the 2d Battalion, and Lieutenant Colonel Sherwood Dixon the 3d Battalion. Lieutenant Colonel Baya M. Harrison commanded the 522d Field Artillery, and Captain Pershing Nakada commanded the 232d Engineers.

Colonel Charles W. Pence, a World War I veteran and military science professor, commanded the regiment until he was wounded during the rescue of the "Lost Battalion" in October 1944. He was then replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Virgil R. Miller.

The US government required that all internees answer a loyalty questionnaire, which was used to register the Nisei for the draft. Question 27 of the questionnaire asked eligible males, "Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?" and question 28 asked, "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization?"

Nearly a quarter of the Nisei males answered with a no or a qualified answer to both questions in protest, resenting the implication they ever had allegiance to Japan; some left them blank. Qualified answers included those who said, yes, but criticized the internment of the Japanese or racism. Many who responded that way were imprisoned for evading the draft. Such refusal is the subject of the postwar novel No-No Boy. But more than 75% indicated that they were willing to enlist and swear allegiance to the U.S. The U.S. Army called for 1,500 volunteers from Hawaii and 3,000 from the mainland. An overwhelming 10,000 men from Hawaii volunteered. The announcement was met with less enthusiasm on the mainland, where most draft-age men of Japanese ancestry and their families were held in concentration camps. The Army revised the quota, calling for 2,900 men from Hawaii, and 1,500 from the mainland. Only 1,256 volunteered from the mainland during this initial call for volunteers. As a result, around 3,000 men from Hawaii and 800 men from the mainland were inducted.

Roosevelt announced the formation of the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team, saying, "Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry." Ultimately, the draft was reinstated to obtain more Japanese Americans from the mainland to become part of the 10,000 men who eventually served in the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regiment.