Since planes were able to fly such long distances the US was afraid of airplane bomber attacks on the mainland. Rather than diverting badly needed military forces they came up with the civilian Aircraft Warning Service. Nearly one million volunteers served in the AWS as volunteer aircraft spotters, helping to defend both US coasts. Even children could help, with a Junior AWS Kit aimed at them. Volunteers manned over 14,000 observation posts 24-hours a day in two-hour shifts.

July 10 - October 31, 1940

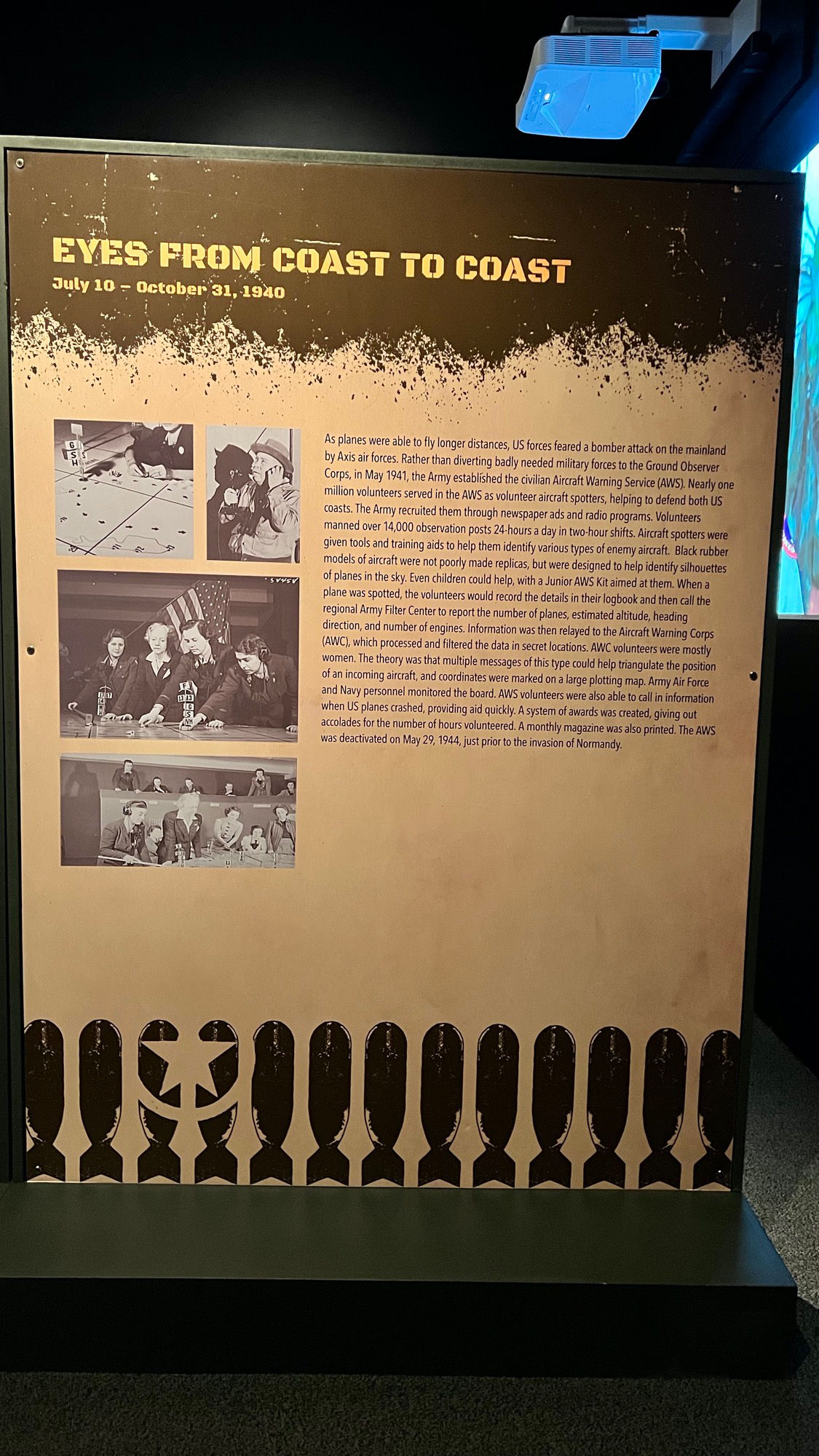

As planes were able to fly longer distances, US forces feared a bomber attack on the mainland by Axis air forces. Rather than diverting badly needed military forces to the Ground Observer Corps, in May 1941, the Army established the civilian Aircraft Warning Service (AWS). Nearly one million volunteers served in the AWS as volunteer aircraft spotters, helping to defend both US coasts. The Army recruited them through newspaper ads and radio programs. Volunteers manned over 14,000 observation posts 24-hours a day in two-hour shifts. Aircraft spotters were given tools and training aids to help them identify various types of enemy aircraft. Black rubber models of aircraft were not poorly made replicas, but were designed to help identify silhouettes of planes in the sky. Even children could help, with a Junior AWS Kit aimed at them.

When a plane was spotted, the volunteers would record the details in their logbook and then call the regional Army Filter Center to report the number of planes, estimated altitude, heading direction, and number of engines. Information was then relayed to the Aircraft Warning Corps (AWC), which processed and filtered the data in secret locations. AWC volunteers were mostly women. The theory was that multiple messages of this type could help triangulate the position of an incoming aircraft, and coordinates were marked on a large plotting map. Army Air Force and Navy personnel monitored the board.

AWS volunteers were also able to call in information when US planes crashed, providing aid quickly.

A system of awards was created, giving out accolades for the number of hours volunteered. A monthly magazine was also printed. The AWS was deactivated on May 29, 1944, just prior to the invasion of Normandy.

1941-1945

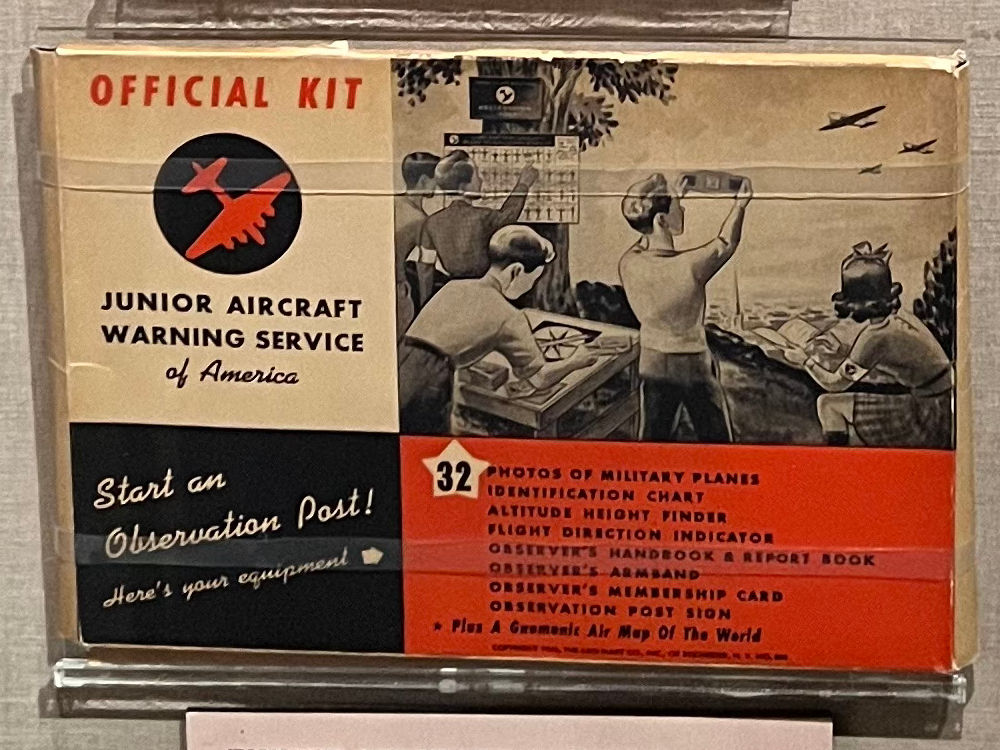

This kit, designed for children to start their own observation posts, contained photos of military aircraft, an altitude height finder, an observer's handbook, a report book, an armband and a membership card.

Aircraft Warning Service

Aircraft Warning Service

1941-1945

1941-1945

Models like these helped observers identify types of aircraft. The P. 47 Thunderbolt was a fighter that usually served as a short-to-medium-range escort fighter.

Aircraft Warning Service

General Orders

For all Observers:

- Keep outside and alert, observe everything that takes place within sight or hearing.

- Report for duty promptly and quit your Post only when properly relieved.

- Receive, obey and pass on to relieving Observers all orders from Officer of the Day and Chief Observers only.

- Read all notices on the Bulletin Board when reporting for duty.

- Follow Flash Message Form in reporting. Report only Flash Messages to the Army Operator.

- Notify the Chief Observer or Officer of the Day of all incidents not covered by instructions.

- Consider all Observation Post information a military secret for discussion with no one.

- Keep your Post in a clean, orderly and comfortable condition.

- Allow no one to commit a nuisance on or near your Post.

- Limit your Post to Observers on duty and duly authorized persons only - challenge strangers promptly.

- Keep your identification Card in your possession at all times and report its loss to your Chief Observer immediately/.

- Surrender your Identification Card and Arm Band for failure to comply with these orders, or upon dismissal or resignation.

Brigadier General, U.S. Army

Commanding

Aircraft Warning Service

Aircraft Warning Service

New York, N.Y.(?). Jan., 1943. Volunteer workers, recruited by the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, maintaining 24-hour watch on aircraft along the three coastal areas.

Library of Congress AIRCRAFT WARNING SERVICE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS One of the thousands of volunteer spotters who relay information from a secret telephone and radio network to the filters and operations centers. At the filter center, each of the girl plotters is in charge of a section of the map. She receives all messages from spotters in her area and places a marker, called a "pip" on the spot where the plane has been observed. The pip is moved on at each new report, leaving a trail of arrows across the map to show the plane's direction. After a plane has been reported three times the pip is removed and replaced by a standard. Pips and standards are pushed into place by volunteer plotters before the watchful eyes of representatives of the air units who sit in a balcony overlooking the board. The Army, the Navy or the Civil Aeronautics Administration must identify all the planes whose standards are placed on the map. Otherwise, the Army Interceptor Command order fighter planes to take off after the unknown plane. Mrs. E.V. Rickenbacker (second from left) watches as a group of volunteer airplane plotters at a filter center push markers into place. Recruited by the Office of Civilian Defense, the volunteers work in shifts of four to five hours, often coming to the center after a day's work at the office. The plotters report every second or third day, contributing many hours to their work than involved in less exacting civilian defense operations.

WIKIPEDIAThe Aircraft Warning Service

Was a civilian service of the United States Army Ground Observer Corps instated during World War II to keep watch for enemy planes entering American airspace. It became inactive on May 29, 1944.During the period from 1919 to the start of World War II, the heavy bomber was created, capable of ranging far from its home base and carrying a lethal load of high explosives. It soon became clear that a warning system was needed to protect against this new threat. Technology at the outset of World War II consisted of mechanical sound detectors that were found to be inadequate to the job. It was also argued that while soldier lookouts would be valuable, their use would detract from other needed military operations.

The answer was found in calling on civilian volunteers to act as airplane spotters. With the help of the American Legion, volunteers were organized in May 1941 into the Aircraft Warning Service, the civilian arm of the Army's Ground Observer Corps.

On both coasts, observation posts, information centers and filter centers were established. The United States entered World War II on Dec 7, 1941. Many of those who could not join the military for whatever reason were recruited to the AWS. Statistically, this led to a preponderance of women.

- On the east coast, the AWS was under the auspices of the Army Air Force's 1st Interceptor Command (later First Fighter Command or I Fighter Command) based at Mitchel Field, New York.

- On the west coast, the AWS was under the auspices of the 4th Interceptor Command (later Fourth Fighter Command or IV Fighter Command) based in Riverside, California.

All observers received extensive training in aircraft recognition. This training was so successful that it spilled over into the non-AWS population. Aircraft recognition became a significant hobby providing many with thousands of hours of entertainment and spawning many books and publications, including flashcards, on the subject. Many participated in contests and recognition "Bees". Recognition clubs and meeting flourished becoming a major social phenomenon of the day. Of significant note to the training effort was the use of black, hard rubber, spotter models for various aircraft. Today, often mistaken for poor quality toys, these models can be worth hundreds of dollars and need to be preserved as part of AWS history.

As the war escalated, thousands of observation posts were established on the east coast from the top of Maine to the tip of Florida, and roughly inland as far as the western slopes of the Appalachian Mountains. On the west coast, posts ranged from upper Washington to lower California. Each post had its own code name and number. When aircraft were spotted, the volunteers would record their observations on forms or in log books and then quickly place a call to a regional Army Filter Center and verbally deliver a "Flash Message" which contained the organized data from the observation. In California these messages were a succinct series of brief phrases describing the number of planes, estimated altitude, heading direction, and number of engines: e.g., "one, high, south east, four"

. One can imagine that aircraft approaching the coast would be spotted by multiple posts, resulting in multiple Flash Messages and, therefore, a reasonably accurate triangulation of position, speed, direction, altitude, etc. At the peak of operation, the Aircraft Warning Service of the First Fighter Command numbered some 750,000 individuals, of whom about 12,000 were in information and filter centers. Practice interceptions, run almost daily provided significant experience to ground officers and pilots working under simulated combat conditions. Because of its huge scope of operations on the East Coast it was able to save the lives of many young pilots by bringing speedy aid to those whose planes had crashed.