He was an American editorial cartoonist who won two Pulitzer Prizes. He drew cartoons about regular dogface soldiers. Famous for two cartoon infantrymen, Willie and Joe, who represented the average American GI. He published six cartoons a week for Stars and Stripes. They were viewed by soldiers throughout Europe and were also published in the United States. Mauldin's cartoons made him a hero to the common soldier.

He drew'em, as he saw'em

One of the first, and sometimes the only, things people think about when they hear the name Bill Mauldin is World War II. His characters Willie and Joe, created for the 45th Division News in 1940, extended to the Mediterranean edition of the Stars and Stripes in November 1943. Mauldin officially transferred to the Mediterranean edition of Stars and Stripes early in 1944 and his editor arranged for syndication by United Feature Service as Up Front at the same time. He won his first Pulitzer for cartooning in 1945.

Mauldin always called it as he saw it. During the war that led him to more than one confrontation with the military brass, including a famous one with General George Patton. In 1944, while technically AWOL in Paris, Mauldin was set up to meet the famous general who did not appreciate the scruffiness of Willie and Joe. In March 1945, he drove up to Luxembourg, to Patton's quarters. Mauldin recounts the meeting in The Brass Ring, in which Patton harangued him:

Now then, sergeant, about those pictures you draw of those god-awful things you call soldiers. Where did you ever see soldiers like that? You know goddamn well you're not drawing an accurate representation of the American soldier. You make them look like goddamn bums. No respect for the army, their officers, or themselves.

Mauldin was permitted to speak his mind to Patton. As he left the general's office, he found Will Lang perched outside.

Patton had received me courteously, had expressed his feelings about my work, and had given me the opportunity to say a few words myself. I didn't think I had convinced him of anything, and I didn't think he had changed my mind much, either.

[]

[https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/swann/mauldin/mauldin-atwar.html]

WIKIPEDIAWilliam Henry Mauldin

October 29, 1921 - January 22, 2003

He was an American editorial cartoonist who won two Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was most famous for his World War II cartoons depicting American soldiers, as represented by the archetypal characters Willie and Joe, two weary and bedraggled infantry troopers who stoically endure the difficulties and dangers of duty in the field. His cartoons were popular with soldiers throughout Europe, and with civilians in the United States as well. His second Pulitzer Prize was for a cartoon published in 1958, and possibly his best-known cartoon was after the Kennedy assassination.After his parents' divorce, Bill and his older brother Sidney moved to Phoenix, Arizona in 1937 and attended Phoenix Union High School. It was there that he began his career in editorial journalism-writing for PUHS's Coyote Journal. Bill did not graduate with his class (he was later granted a diploma in 1945) and in 1939 he took courses at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts where he studied political cartooning with Vaughn Shoemaker.

Shortly after returning to Phoenix in 1940, Mauldin enlisted in Company D, 120th Quartermaster Regiment, of the Arizona National Guard, at Phoenix, Arizona. His division, the 45th Infantry Division, was federalized just two days later. While in the 45th, Mauldin volunteered to work for the unit's newspaper, drawing cartoons about regular soldiers or "dogfaces". Eventually he created two cartoon infantrymen, Willie and Joe, who represented the average American GI.

During July 1943, Mauldin's cartoon work continued when, as a sergeant of the 45th Infantry Division's press corps, he landed with the division in the invasion of Sicily and later in the Italian campaign. Mauldin began working for Stars and Stripes, the American soldiers' newspaper; as well as the 45th Division News, until he was officially transferred to the Stars and Stripes in February 1944. Egbert White, editor of the Stars and Stripes, encouraged Mauldin to syndicate his cartoons and helped him find an agent. By March 1944, he was given his own jeep, in which he roamed the front, collecting material. He published six cartoons a week. His cartoons were viewed by soldiers throughout Europe during World War II, and were also published in the United States. The War Office supported their syndication, not only because they helped publicize the ground forces but also to show the grim side of war, which helped show that victory would not be easy. While in Europe, Mauldin befriended a fellow soldier-cartoonist, Gregor Duncan, and was assigned to escort him for a time. (Duncan was killed at Anzio in May 1944.)

Mauldin was not without his detractors. His images-which often parodied the Army's spit-shine and obedience-to-orders-without-question policy-offended some officers. After a Mauldin cartoon ridiculed Third Army commander General George Patton's decree that all soldiers be clean-shaven at all times-even in combat-Patton called Mauldin an "unpatriotic anarchist" and threatened to "throw ass in jail" and ban Stars and Stripes from his command. General Dwight Eisenhower, Patton's superior, told Patton to leave Mauldin alone; he felt the cartoons gave the soldiers an outlet for their frustrations. "Stars and Stripes is the soldiers' paper," he told him, "and we won't interfere."

In a 1989 interview, Mauldin said, "I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn't like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes."

Mauldin's cartoons made him a hero to the common soldier. GIs often credited him with helping them to get through the rigors of the war. His credibility with the common soldier increased in September 1943, when he was wounded in the shoulder by a German mortar while visiting a machine gun crew near Monte Cassino. By the end of the war, he received the Legion of Merit for his cartoons. Mauldin wanted Willie and Joe to be killed on the last day of combat, but Stars and Stripes dissuaded him.

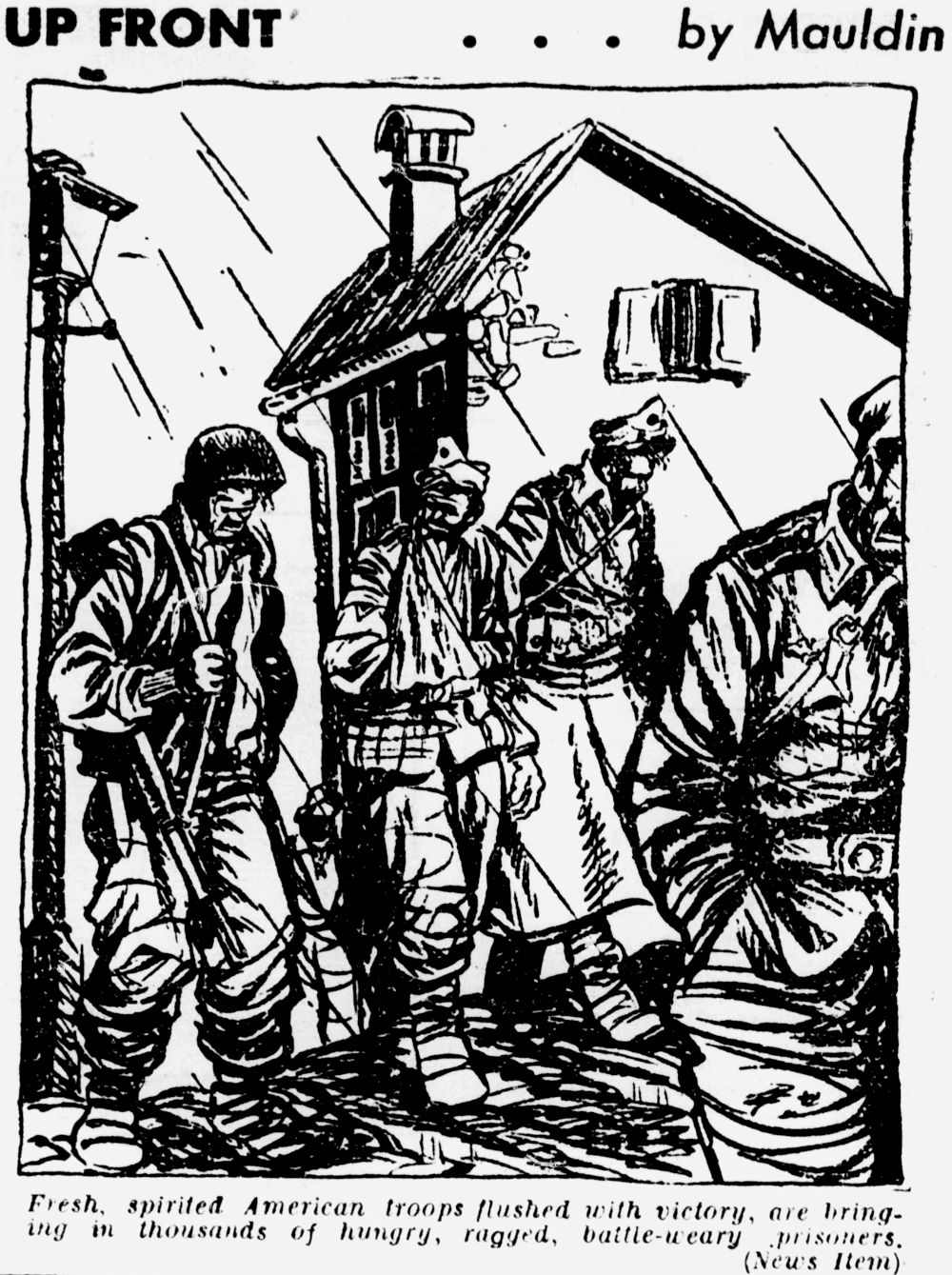

In 1945, at the age of 23, Mauldin won a Pulitzer Prize for his wartime body of work, exemplified by a cartoon depicting exhausted infantrymen slogging through the rain, its caption mocking a typical late-war headline: "Fresh, spirited American troops, flushed with victory, are bringing in thousands of hungry, ragged, battle-weary prisoners". The first civilian compilation of his work, Up Front, a collection of his cartoons interwoven with his observations of war, topped the best-seller list in 1945. After the war's end, the character of Willie was featured on the cover of Time magazine for the June 18, 1945, issue.

WIKIPEDIABill Mauldin

Willie and Joe are stock characters representing United States infantry soldiers during World War II. They were created and drawn by American cartoonist Bill Mauldin from 1940 to 1948, with additional drawings later. They were published in a gag cartoon format, first in the 45th Division News, then Stars and Stripes, and starting in 1944, a syndicated newspaper cartoon distributed by United Feature Syndicate.Mauldin was an 18-year-old soldier training with the 45th Infantry Division in 1940. He cartooned part-time for the camp newspaper. Near the end of 1941 the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the USA entered World War II. Mauldin was sent to combat, influencing his cartoons. They gradually became darker and more realistic in their depiction of the weariness of the enduring miseries of war. He extended the bristles on their faces and the eyes – "too old for those young bodies", as Mauldin put it – showed how much Willie and Joe suffered. In most cartoons, they were shown in the rain, mud, and other dire conditions, while they contemplated the whole situation.

In the early cartoons, depicting stateside military life in barracks and training camps, Willie was a hook-nosed, smart-mouthed Chocktaw Indian, while Joe was his red-necked straight man. But over time, the two became virtually indistinguishable from each other in appearance and attitude.

The cartoons were published in the 45th Division News from 1940 until November 1943, when the Mediterranenean edition of the Stars and Stripes took them over. Starting April 17, 1944, Mauldin's editor arranged for syndication by United Feature Syndicate as Up Front. As of 1945, according to a Time report, the cartoons were published in 139 newspapers. The title changed to Sweatin' It Out on June 11, 1945, then Willie and Joe on July 30, 1945. The strip lasted until April 8, 1948.

PBSBill Mauldin

Many people have described their wartime experiences in letters home. But very few have chronicled war for the people doing the fighting. Bill Mauldin, World War II's most famous cartoonist, is one of them. In 1943, when he was 21, Mauldin's division shipped overseas to North Africa. Mauldin had been drawing cartoons since he was a boy, and he was quickly assigned to cover the war for the 45th Division News, and then for Stars and Stripes. His cartoons, featuring a scruffy pair of foot soldiers named Willie and Joe, scored an instant hit with the soldiers who saw them. Within two years, Mauldin won fame - and a Pulitzer Prize - for capturing foot soldiers' everyday experiences.As Mauldin described his famous GIs, "they matured overseas during the stresses of shot, shell, and K-rations, and grew whiskers because shaving water was scarce in mountain foxholes." Enjoy this sampling of Mauldin's work, courtesy of his publisher, Presidio Press.

WIKIPEDIAEditorial Cartooning

Sergeant Bill Mauldin of United Feature Syndicate, Inc. for distinguished service as a cartoonist, as exemplified by the cartoon entitled, "Fresh, spirited American troops, flushed with victory, are bringing in thousands of hungry, ragged, battle-weary prisoners", in the series entitled, Up Front With Mauldin.

WIKIPEDIAEditorial Cartooning

William H. (Bill) Mauldin of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, for "I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?", published on October 30, 1958.