Clothing Restrictions in WWII

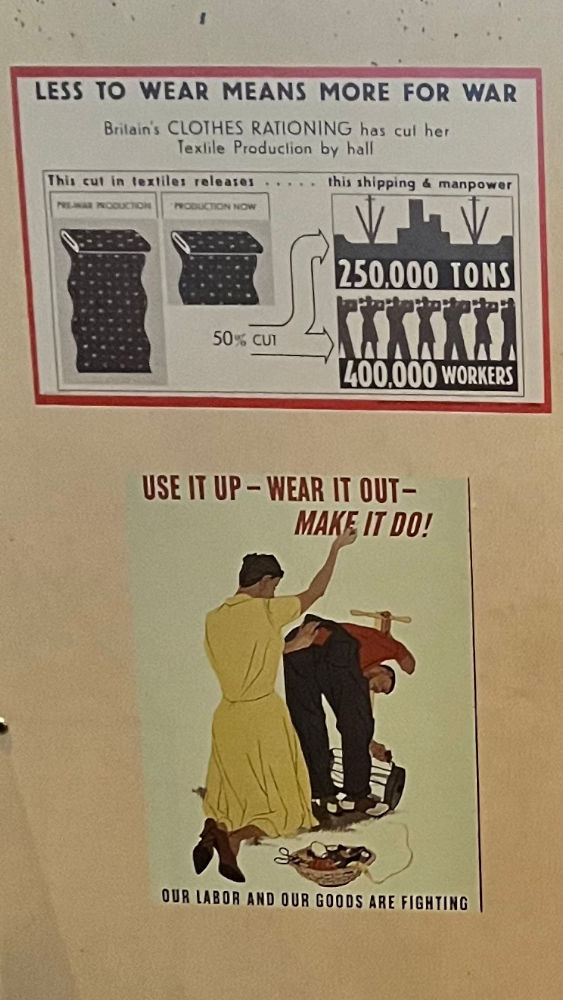

Fabric and clothing, as with so much, had to be prioritized for the war effort. Millions of uniforms needed to be created, and wool was the primary fabric they were made from silk, which was no longer able to be imported from Japan, was needed for parachutes and gunpowder bags. Nylon was used for parachutes and ropes. Civilian clothing was made from cotton, rayon, or rayon blends. In the US, there were restrictions on the amount and types of fabric. The US War Production Board (WPB) issued order L-85 on March 8, 1942, calling for a 15 percent reduction in the textiles used in commercial women's clothing. In the UK, clothing was rationed, and coupons were needed to purchase clothes and shoes. Clothing was mended and patched, and when no longer wearable, was turned into rags or donated to scrap drives.

With these restrictions, clothing became more utilitarian, and some resembled military uniforms. The Victory suit was single breasted instead of double breasted with narrow lapels, and no cuffs, pocket flaps, or matching vest. In women's clothing, silhouettes were slimmer, skirts were shorter, and ruffles disappeared in order to construct garments with as little fabric as possible. Fabric belts were limited to 2" and garments could not have more than one pocket. Women, now working in factories, were seen more often in trousers, with turbans, snoods, and headscarves to keep hair away from the machinery. Women also cut down men's suits that were no longer needed when their wearers were overseas, and remade them for themselves. Last year's garments were updated with a new collar or buttons. Red, white, and blue patriotic clothing was popular.

Leather and rubber was needed for shoes, so civilian shoes were rationed.

Beginning on February 9, 1943, every person had stamps that could be used to purchase up to three pairs of leather shoes a year, and the next year it was dropped to two pairs a year.

More than that required a lengthy justification.

Fabric shoes like espadrilles and many wedges, were not restricted.

Purses were made of fabric rather than leather.

Stockings, made of silk or nylon, were hard to come by, and even used stockings could be remade into gunpowder backs or melted back down and re-spun into thread.

In order to give the illusion of wearing stockings, women darkened their legs with gravy or makeup and drew seam lines up the back of their legs with eyeliner.

Leather and rubber was needed for shoes, so civilian shoes were rationed.

Beginning on February 9, 1943, every person had stamps that could be used to purchase up to three pairs of leather shoes a year, and the next year it was dropped to two pairs a year.

More than that required a lengthy justification.

Fabric shoes like espadrilles and many wedges, were not restricted.

Purses were made of fabric rather than leather.

Stockings, made of silk or nylon, were hard to come by, and even used stockings could be remade into gunpowder backs or melted back down and re-spun into thread.

In order to give the illusion of wearing stockings, women darkened their legs with gravy or makeup and drew seam lines up the back of their legs with eyeliner.

Home sewers and knitters, while not restricted, tended to follow the WPB guidelines. They also volunteered to make clothing and accessories for service members: bandages, mittens, vest, and scarves.

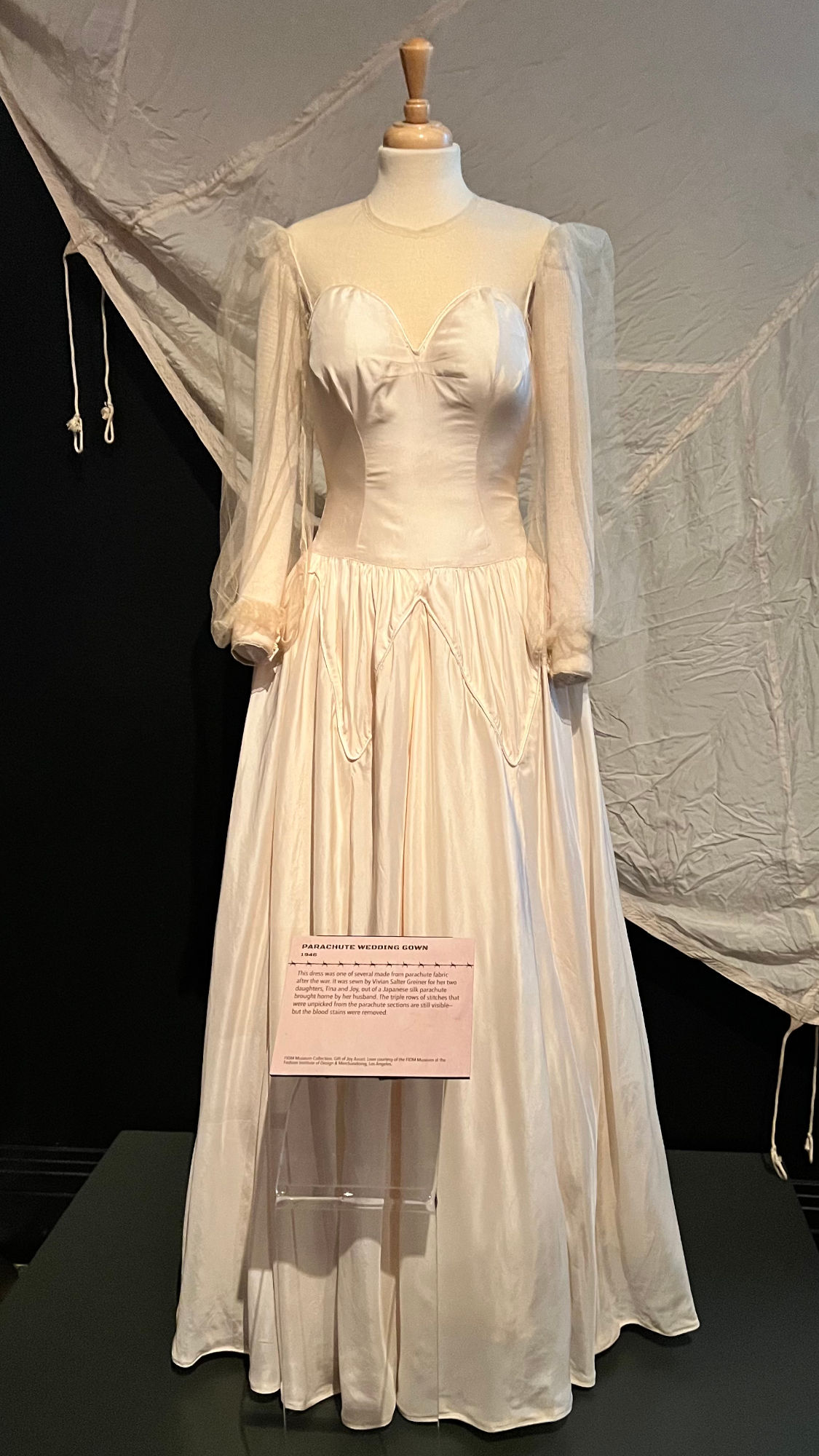

After the war there were still scarcities of fabric. Parachutes were recut and sewn into wedding gowns, and gowns were shared by multiple women. Even Queen Elizabeth II, then Princess Elizabeth, used ration coupons to purchase the material for the gown she wore to her wedding November 20, 1947.

1946

This dress was one of several made from parachute fabric after the war. It was sewn by Vivian Salter Greiner for her two daughters, Tina and Joy, out of a Japanese silk parachute brought home by her husband. The triple rows of stitches that were unpicked from the parachute sections are still visible - but the blood stains were removed.

1942-1945

The British Board of Trade's 1941 Civilian Clothing Restriction Order limited such things as number of buttons, heel height, and amount of decoration on new items. The CC41 logo was found on clothing, like this bra, that conformed to those rules and were able to be purchased tax free.

1942-1945

This swimsuit is just one example of the patriotic designs in wartime clothing.

1942-1944

The March 20, 1941 issue of Marie Claire magazine gave instructions on how to make these types of shoes out of rope or sisal. The soles are hand cut out of whatever durable material was available. The ribbons were added in 1944 to celebrate the liberation of Paris.

1945

1941

Probably made by a home sewer, this dress features a pattern reading "There'll Always be England", a line from a 1939 British song. Printed in "Buckingham (Palace] Brick" and "Blackout Black" colors, the writing is printed backwards - a nod to coded messages used by the military during the war.

National Park ServiceEven before the US formally entered World War II, there was a demand for materials to supply the Allies. But there was greater demand on the part of American manufacturers to supply products for civilians. A report examining American preparation for war noted that, in 1941, US factories made more articles for civilian use than ever before. In response, the US government ordered production cuts to strip off some of this "fat." They targeted items like cars, lawn mowers, juke boxes, "fancy galoshes," and other items. With these limits imposed, the government estimated that $20 billion in capacity could be used for military production.In World War I and before the US entered World War II, the government asked people to ration voluntarily.[12] This approach was unsuccessful. Instead, people hoarded products and costs rose, and those without money simply went without needed goods.

In January 1942, just a few weeks after the Japanese attacks in the Pacific, the federal government mandated rationing. This limited the availability of certain goods and materials and ensured fair distribution, given the needs of the war.

Establishing maximum or ceiling prices for rationed goods also helped to keep inflation in check. Using their nation-wide overview of supply, demand, and the economy, the federal government dictated which items to ration, set ceiling prices, and allocated available supply.

Rationing was overseen by the federal Office of Price Administration (OPA) in conjunction with other war offices, including the Wartime Production Board (WPB). It was managed at the local level by volunteer rationing boards. At their local rationing offices, people registered for and received their ration books, and could apply for ration certificates or additional coupons. When the war ended, over 100,000 citizen volunteers were managing the program organized into about 5,600 local boards.[13]

The ration program had four systems:

- Certificate Rationing for items like tires, cars, and stoves that required applying for a certificate to buy

- Differential Coupon Rationing for things like gasoline and heating oil that some people needed more than others

- Uniform Coupon Rationing for things like shoes, sugar, and coffee rationed at fairly stable amounts per person

- Point Rationing for items like meats and canned goods where supply and demand varied greatly[14]

In each of these four systems, to buy something, shoppers had to produce the right ration coupons, stamps, certificates, or points plus the cost of the item. To control the rate of spending and discourage hoarding, coupons and stamps expired at set times. [15] The OPA added and removed items from the ration list throughout the war. Rationing ended as goods became available. By the end of 1945, the only thing still rationed was sugar. It remained under ration until June 1947. [16]

Despite the best efforts of the government, the volunteer rationing boards, the police, and civilian defense workers, there were many people who found ways to work around the ration system. These included theft, counterfeiting, hoarding, fraud, and organized crime in illicit trade, also called the black market.

On January 16, 1942, just over one month after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States' subsequent entrance into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9024 which established the War Production Board. This board was commissioned to "exercise general direction over the war procurement and production program." Its primary task was to convert civilian industries into war industries and to adapt American industrial life to support the war effort.A key way to accomplish that mission was by reallocating materials deemed necessary for military success, such as steel, wool, and nylon. In order to ensure that certain materials would be readily available for war production, the War Production Board issued General Limitation Order L-85 on April 8, 1942.

Library of CongressRegulation L-85

This order placed limitations on feminine apparel. The order specified the amount of fabric that could be used to create a garment and listed the measurements for feminine apparel items. For example, hems and belts could not exceed two inches in width, garments could not have more than one pocket, and ornamental sleeves, hoods, and scarves were banned.The American fashion industry quickly responded to this new rationing system by emphasizing simple silhouettes. New designs made "the most of every inch of material allotted to civilian use" and focused on slim, slender lines. Evening dresses were "straight and narrow", and the simple, well-tailored look was considered exceptionally chic. Articles that discussed the new fashion trends also emphasized the importance of careful selection and "wardrobe planning" before purchasing any new clothing. A woman's patriotic duty to ration and support the war effort was still more important than keeping up with the fashion. Moderation was key.

One of the most difficult changes women had to face was the rationing of nylon. Throughout the 1930s, silk stockings were a staple in women's fashion. With the outbreak of World War II and growing animosity with Japan, however, citizens wanted to reduce their reliance on silk as 90 percent of silk used in the United States was imported from Japan. Nylon became the new stocking material of choice and was quickly loved by women throughout the country. When the new stockings were released in stores in May 1940, four million pairs sold out in two days and thousands of women flocked to their nearest department store.

Unfortunately, nylon was soon reallocated into parachutes, ropes, and netting manufacturing for the war. Shorter hemlines under Regulation L-85 meant that women had to cover up, but without their beloved nylon stockings, women had to get creative. Instead, they turned to the next best thing: makeup. Women would paint their legs with foundation to give the illusion of nylon stockings, including drawing a "seam" on the back of their legs to complete the deception. Special devices were created to simplify the process and department stores even had "leg makeup bars" where women could have their nylons painted on by a professional makeup artist.

By the time rationing was over, women could not wait to get their hands on real nylon stockings once again. 1946 saw intense "Nylon Riots" in cities such as Pittsburgh, where more than 30,000 women rushed to buy their favorite accessory.

The simple clothing styles and creative fashion trends of the 1940s soon came to an end as the war and clothing rationing ended in 1945. By the end of the year, the only thing still being rationed was sugar. As civilian life slowly began to create a new post-war culture, so too did fashion styles.

In February 1947, fashion designer Christian Dior unveiled his new post-war style, dubbed by fashion critics as "The New Look." This look was the antithesis of clothing created under the order of Regulation L-85. Rounded shoulders, a cinched waist, and a long, full skirt characterized Dior's "New Look" and quickly became a staple of 1950s fashion. Before long, clothing that reflected the restrictions of Regulation L-85 had disappeared as women were excited to experiment with fashion once again. Clothing rationing during World War II not only influenced fashion during the war, but greatly inspired trends that would come to define post-war culture, and beyond.

National ArchivesRosie the Riveter

Because women were now taking on more labor-intensive tasks like driving trucks, flying military aircraft, and working in shipyards, safety and practicality took precedence over glamour and femininity. The popularization of "Rosie the Riveter" meant that slacks and headscarves were considered stylish.SAME WWII EXHIBIT RELATED: [eatlife.net/wwii/rosie-the-riveter.php]

Working women traded in their high-heeled shoes and silk pants for khaki jackets and blue jeans. They also began wearing wraparound dresses with fewer adornments and pinned their hair back to avoid getting it caught in the machinery.

Pragmatism aside, women's clothing also needed to adapt to the rationing of certain materials for military purposes. Wool and silk were in high demand for uniforms and parachutes; most civilians wore clothes made from rayon or viscose instead.

To conserve fabric, dressmakers and manufacturers began designing shorter skirts and slimmer silhouettes. Nylon was only available for civilian use in restricted quantities, so stockings soon disappeared and women went barelegged.

By the end of the war, over 6 million American women had joined the workforce, and nearly one out of every four married women worked outside the home. Although many were ultimately replaced by men once they returned from war, it is remarkable what women accomplished on a national scale in just four short years.

These women demonstrated patriotism, skill, and determination, making an undeniable impact on the workplace-and the fashion world.