They did not merely speak in their native tongue; another level of security needed to be added for the Code, It varied by branch of service and by tribe. Coded terms for words with no native equivalents were developed. These codes were not written down on anything taken in the field, and the Code Talkers had to memorize all the terms. The number of men in the programs was kept small, and everyone could identify each other's voices, so no one could pose over the radio as a Code Talker.

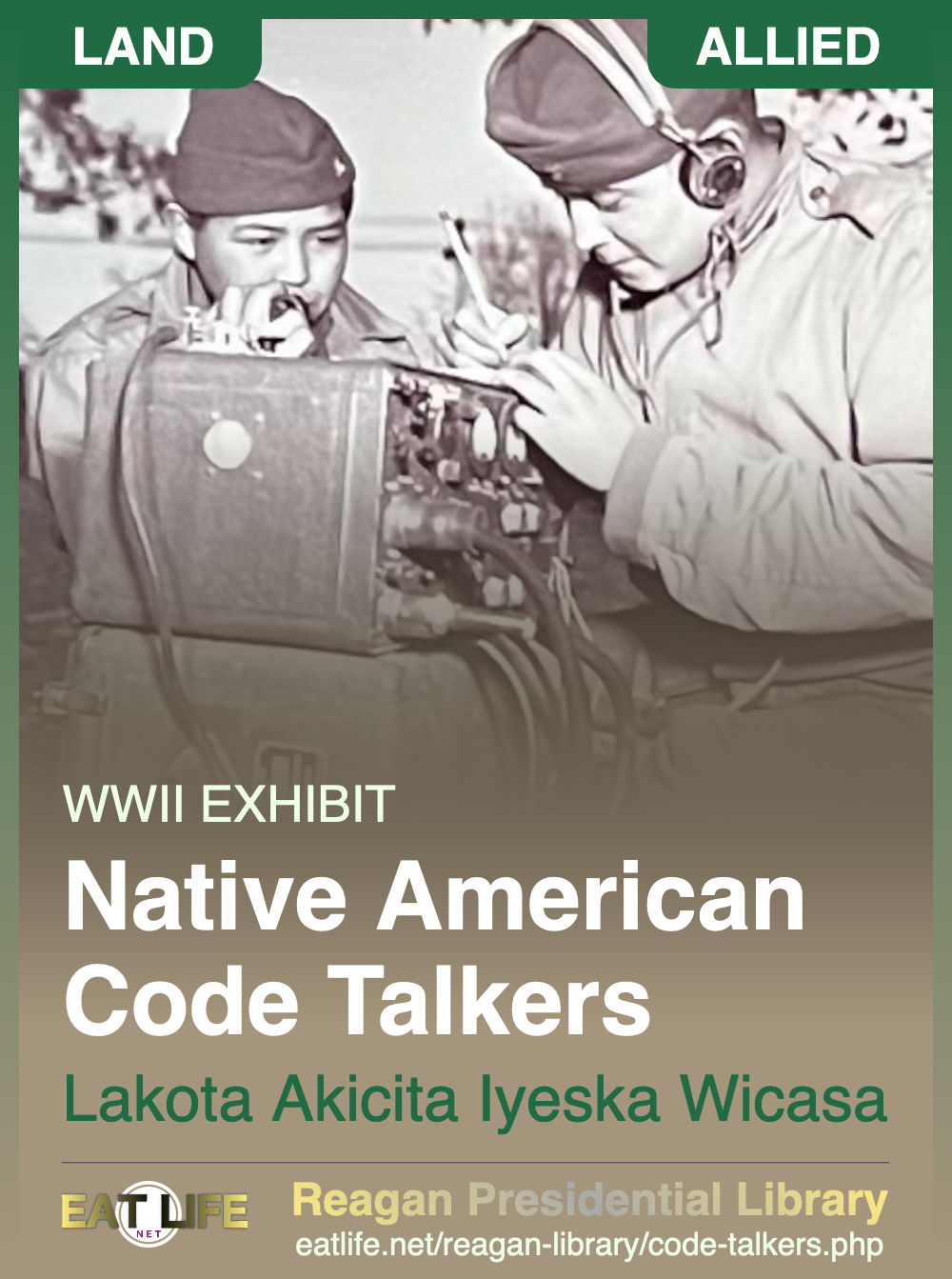

Lakota Akicita Iyeska Wicasa

(Indian Soldier Translator Man)

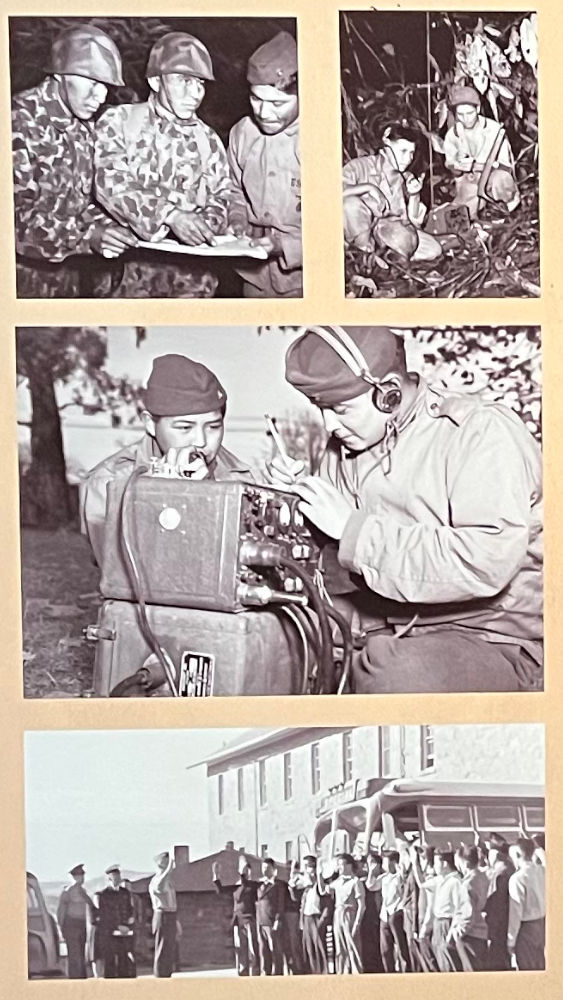

There were around 44,000 Native Americans who served in WWII. Many of them used their native tongues to pass on messages, with a smaller number trained in a secret code based on those languages. Code Talkers were recruited into the armed forces, without being told what for. If they passed basic and more specialized radio or communications training, then they were brought into the program. Most Code Talkers served in pairs, with one man operating the radio and the other relaying and translating the messages.

Navajo Code Talkers served as Marines in the Pacific, while other tribes served with the Army in the European and Pacific theaters. They included twenty-nine Navajo, seventeen Comanche, a dozen Sioux, and four Choctaw. Other Native Americans who used their native languages to pass messages included members of the Cherokee, Kiowa, Hopi, Seminole, Muscogee Creek, and Pawnee tribes, in campaigns from the Aleutian Islands to the Philippines to the liberation of concentration camps.

The Navajo Marines were the first to see combat in WWII, in Guadalcanal in 1942. The first Army Code Talkers in combat were Meskwaki in Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942. "MacArthur's Boys" were members of the Sioux Nation assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division under General Douglas MacArthur in the Pacific. Ogalala Lakota Clarence Wolf Guts was the personal Code Talker for MG Paul Mueller, commander of the 81st Infantry. Mueller had kept an eye out for Native speakers in his units, and employed Sioux and Hopi tribal members. Sioux Code talkers would sneak beyond enemy lines and relay their findings in Lakota or Dakota.

Comanche Code Talker Larry Saupitty, the personal Code Talker to BG Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., sent the first Comanche message on D-Day at Utah Beach when they landed 2,000 yards from their target.

"We made a good landing," he spoke over the radio. "We landed at the wrong place."

Comanche Code Talker Larry Saupitty, the personal Code Talker to BG Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., sent the first Comanche message on D-Day at Utah Beach when they landed 2,000 yards from their target.

"We made a good landing," he spoke over the radio. "We landed at the wrong place."

Peter MacDonald served as Navajo Code Talker in the South Pacific and North China with the Sixth Marine Division. During Iwo Jima, six Navajo Code Talkers successfully transmitted more than 800 messages, including calling in artillery strikes on Japanese positions, and did so without any errors. One of them was Samuel Holiday, who later said, "They sent us wherever they needed us, wherever we were most dangerous."

These men were not able to discuss their wartime heroics, even with their families. The Code Talker program wasn't declassified until 1968.

- Navajo Code: DIBEH AH-NAH, A-SHIN, BE, AH-DEEL-TAHI, D-AH, NA-AS-TSO-SI, THAN-ZIE, TLO-CHIN

- Translation: SHEEP, EYES, NOSE, DEER, BLOW UP, TEA, MOUSE, TURKEY, ONION

- Deciphered Code: SEND DEMOLITION TEAM TO

Dineh Ba Whoa Blehi

(Booby Trap)

Throughout much of US history, there was a push to assimilate Native Americans, and to discourage them from speaking their native languages. These languages, however, became one of the keys to winning the war, forming the basis for the only code systems that were not broken during the war. Choctaw had served as the first code talkers in WWI, along with Cherokees, Comanches, Cheyennes, and Osages, but the program was expanded in WWII.

They did not merely speak in their native tongue; when they did it was classified as non-coded language. European and Asian scholars had studied Native American cultures and languages over the years, even languages that did not have a written form. Another level of security needed to be added for the Code, which varied by branch of service and by tribe. These codes were not written down on anything taken in the field, and the Code Talkers had to memorize all the terms. These codes were much faster than any encrypted machine: 20 seconds vs 30 minutes. The number of men in the programs was kept small, and everyone could identify each other's voices, so no one could pose over the radio as a Code Talker.

Coded terms for words with no native equivalents were developed. In Choctaw, the word machine gun was "little gun shoot fast." In Navajo, "besh-lo" (iron fish) meant submarine and "dah he-tih-hi" (hummingbird) meant "fighter plane. Types of ships, names of months, and other military terms were given related native terms, such as "Gold Oak Leaf" for a Major or "Crusted Snow" for December. For the Comanche, machine guns were "tutsahkuna tawo'i" (sewing-ma-chine gun), tanks were wakaree'e (turtle), and "Po'sa taiboo'" (Crazy White Man) meant Hitler.

When a Navajo code talker receives a message, he might hear a string of seemingly unrelated Navajo words. The code talker first had to translate each Navajo word into its English equivalent, and then only use the first letter to spell out the message. The Navajo words "wol-la-chee" (ant), "be-la-sana" (apple) and "tse-nill" (axe) all stood for the letter "a," adding an additional layer of complication for anyone trying to decipher the code. Plus Navajo relies on tonal inflection, so a change in pitch can mean an entirely different word. Also, the number of native languages used made things more difficult. An enemy would need to identify what language was being spoken before they could find someone who could translate and figure out how to decipher that language's code.

Not that Axis forces did not try. The Japanese were able to determine that Navajo was used. They would also torture Native Americans servicemen they took prisoner, whether they were part of the Code Talkers or not, or even from one of the participating tribes. Even if they could understand the message it would sound like nonsense. If a Code Talker was taken, the code was simply changed.

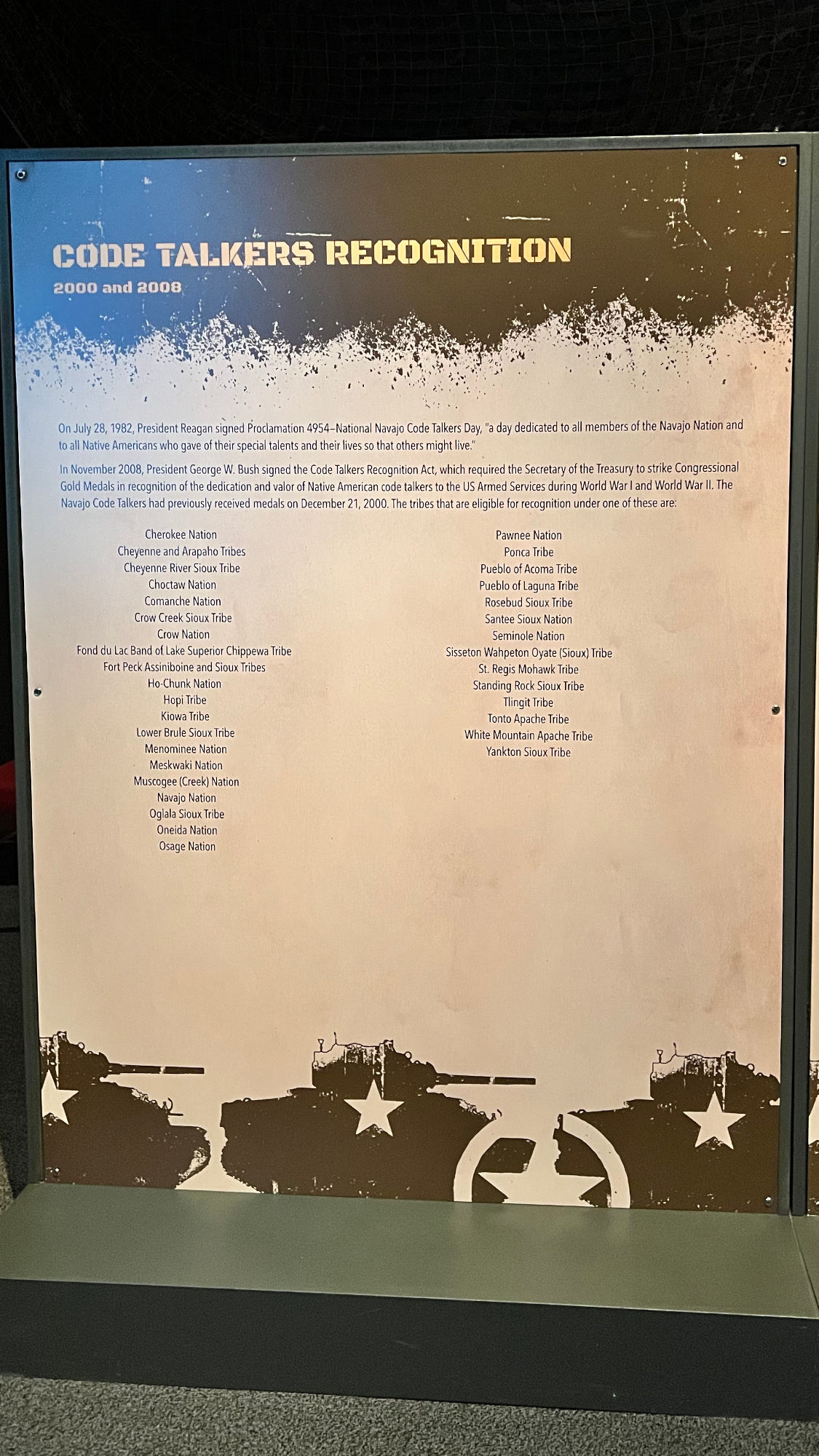

2000 and 2008

On July 28, 1982, President Reagan signed Proclamation 4954- National Navajo Code Talkers Day, "a day dedicated to all members of the Navajo Nation and to all Native Americans who gave of their special talents and their lives so that others might live."

In November 2008, President George W. Bush signed the Code Talkers Recognition Act, which required the Secretary of the Treasury to strike Congressional Gold Medals in recognition of the dedication and valor of Native American code talkers to the US Armed Services during World War I and World War II.

The Navajo Code Talkers had previously received medals on December 21, 2000.

The tribes that are eligible for recognition under one of these are:

- Cherokee Nation

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes

- Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe

- Choctaw Nation

- Comanche Nation

- Crow Creek Sioux Tribe

- Crow Nation

- Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Tribe

- Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes

- Ho-Chunk Nation

- Hopi Tribe

- Kiowa Tribe

- Lower Brule Sioux Tribe

- Menominee Nation

- Meskwaki Nation

- Muscogee (Creek) Nation

- Navajo Nation

- Oglala Sioux Tribe

- Oneida Nation

- Osage Nation

- Pawnee Nation

- Ponca Tribe

- Pueblo of Acoma Tribe Pueblo of Laguna Tribe

- Rosebud Sioux Tribe

- Santee Sioux Nation

- Seminole Nation

- Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (Sioux) Tribe

- St. Regis Mohawk Tribe

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe

- Tlingit Tribe

- Tonto Apache Tribe

- White Mountain Apache Tribe

- Yankton Sioux Tribe

1942-1945

The 4th Signal Company, 4th Division, comprised of members of the Comanche Tribe of Oklahoma. 17 soldiers served in the US Army as Comanche Code Talkers, passing coded messages in the European Theater. The 4th Division landed at Utah Beach on D-Day under Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr, and fought in the Battle of the Bulge.

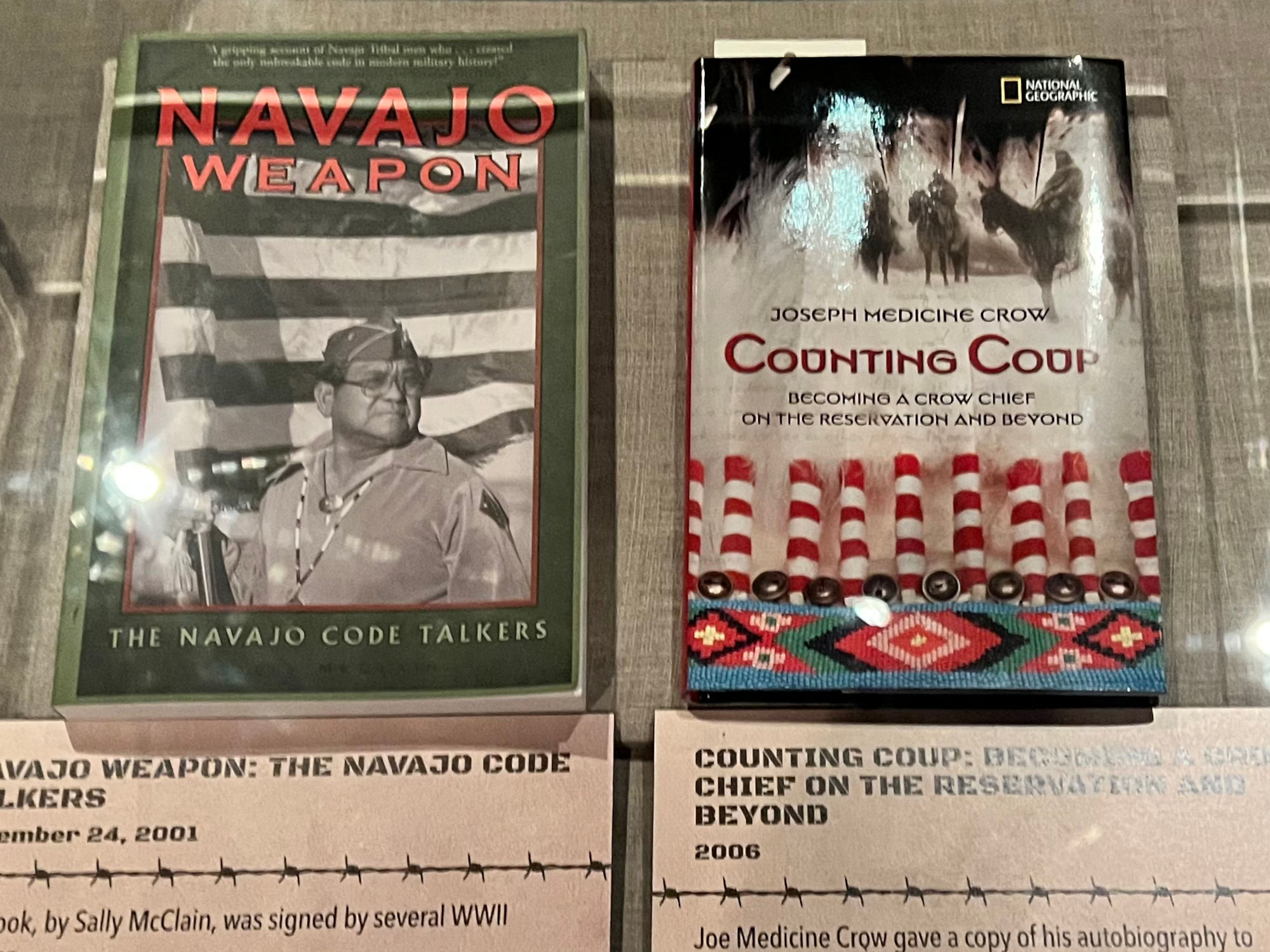

- Navajo Weapon: The Navajo Code Talkers

November 24, 2001

This book, by Sally McClain, was signed by several WWII veterans - Counting Coup: Becoming a Crow Chief on the Reservation and Beyond

2005

Joe Medicine Crow gave a copy of his autobiography to President Obama when he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom on August 12, 2009.

Samuel Tom Holiday was a Navajo code talker who served in the 25th Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division, and was at Saipan, Tinian, and Iwo Jima. He would locate enemy positions and call for artillery strikes using the Navajo Code. He gave this silver and turquoise Navajo necklace to Laura Bush when she visited Arizona.

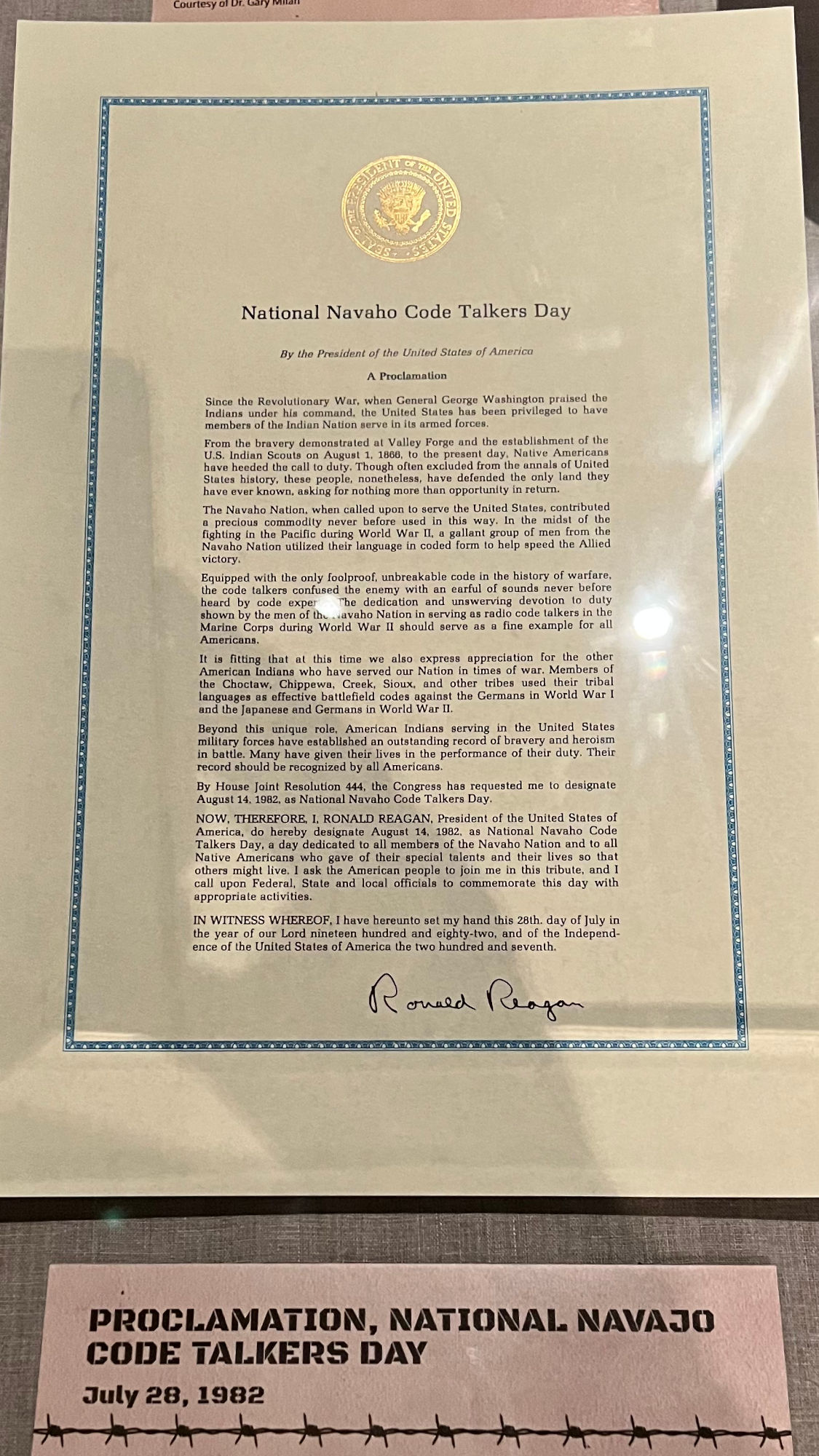

July 28, 1982

National Navaho Code Talkers Day

By the President of the United States of America

A Proclamation

Since the Revolutionary War, when General George Washington praised the Indians under his command, the United States has been privileged to have members of the Indian Nation serve in its armed forces.

From the bravery demonstrated at Valley Forge and the establishment of the U.S. Indian Scouts on August 1, 1866, to the present day, Native Americans have heeded the call to duty. Though often excluded from the annals of United States history, these people, nonetheless, have defended the only land they have ever known, asking for nothing more than opportunity in return.

The Navaho Nation, when called upon to serve the United States, contributed a precious commodity never before used in this way. In the midst of the fighting in the Pacific during World War II, a gallant group of men from the Navaho Nation utilized their language in coded form to help speed the Allied victory.

Equipped with the only foolproof, unbreakable code in the history of warfare, the code talkers confused the enemy with an earful of sounds never before heard by code experts. The dedication and unswerving devotion to duty shown by the men of the Navaho Nation in serving as radio code talkers in the Marine Corps during World War II should serve as a fine example for all Americans.

It is fitting that at this time we also express appreciation for the other American Indians who have served our Nation in times of war. Members of the Choctaw, Chippewa, Creek, Sioux, and other tribes used their tribal languages as effective battlefield codes against the Germans in World War I and the Japanese and Germans in World War II.

Beyond this unique role, American Indians serving in the United States military forces have established an outstanding record of bravery and heroism in battle. Many have given their lives in the performance of their duty. Their record should be recognized by all Americans.

By House Joint Resolution 444, the Congress has requested me to designate August 14, 1982, as National Navaho Code Talkers Day.

Now, Therefore, I, Ronald Reagan, President of the United States of America, do hereby designate August 14, 1982, as National Navaho Code Talkers Day, a day dedicated to all members of the Navaho Nation and to all Native Americans who gave of their special talents and their lives so that others might live. I ask the American people to join me in this tribute, and I call upon Federal, State and local officials to commemorate this day with appropriate activities.

In Witness Whereof, I have hereunto set my hand this 28th day of July in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and eighty-two, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and seventh.

Ronald Reagan

National ArchivesAs Americans and Japanese troops fought island to island in the Pacific during World War II, the Japanese used their considerable skill as code breakers to intercept many messages being sent by American forces. After the war, however, Japan's own chief of intelligence admitted there was one code they were never able to break-the Navajo code used by the Marine Corps. This is the story of that code and the men who made it work for the Marines.The original twenty-nine Navajo "code talkers" received the Congressional Gold Medal, and subsequent code talkers received the Congressional Silver Medal. Their unbreakable code helped the U.S. Marine Corps battle across the Pacific from 1942 to 1945. Until 1968, they and their code remained secret. Their story further comes to national attention when the motion picture Windtalkers opens in June 2002. Written and photographic records in the National Archives document the code talkers' wartime contributions and tell us how this unusual military program got started.

Maintaining secrecy, particularly during wartime, is vital to the national security of every country. On the battlefield, secrecy is essential for victory, and breaking enemy codes is necessary to gain the advantage and shorten the war.

During World War II, sending and receiving codes without the risk of the enemy deciphering the transmission required hours of encrypting and decrypting the code. The U.S. Marine Corps, in an effort to find quicker and more secure ways to send and receive code, enlisted Navajos as code talkers.

At Camp Elliott the initial recruits, along with communications personnel, designed the first Navajo code. This code consisted of 211 words, most of which were Navajo terms that had been imbued with new, distinctly military meanings. For example, "fighter plane" was called "da-he-tih-hi," which means "hummingbird" in Navajo, and "dive bomber" was called "gini," which means "chicken hawk." In addition, the code talkers also designed a system that signified the twenty-six letters of the English alphabet. For example, the letter A was "wol-la-chee," which means "ant" in Navajo, and the letter E was "dzeh," which means "elk." Words that were not included in the 211 terms were spelled out using this alphabet.

The Navajos soon demonstrated their ability to memorize the code and to send messages under adverse conditions similar to military action, successfully transmitting the code from planes, tanks, or fast-moving positions. The program was deemed so successful that an additional two hundred Navajos were recommended for recruitment as messengers on July 20, 1942. Philip Johnston offered his services as a staff sergeant to help develop the code talker program. On October 2, 1942, Johnston enlisted and began training his first class in November and spent the remainder of the war training additional Navajo recruits. After the new recruits went through the Marine Corps's basic training course, they came to Johnston for what he termed an "extremely intensive" eight-week messenger training course.

As the code talker program grew, so did the development of the code. A cryptographer who monitored the code talkers' transmissions concluded that the code might be broken because using the alphabet to spell out words not in the Navajos' vocabulary produced too many repetitions. The code talker alphabet therefore grew from twenty-six to forty-four terms by expanding the number of words used for the most frequently repeated letters- E, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, L, and U. For example, the letter A could be designated by the words "be-la-sana" and "tse-nihl," which mean "apple" and "axe," as well as the original "wol-la-chee," meaning "ant." The original 211 vocabulary terms were also expanded to 411.

Despite the development of unique military terms for the Navajo code, the lack of military terminology in the original Navajo vocabulary remained an obstacle. Because the Navajo messengers had trained at different times and worked in different locales, the development of certain dialects and modified vocabularies was inevitable. To offset this problem, officers frequently exchanged Navajos from one division into another to try to ensure that all code talkers used a standard code. Problems persisted, however, and after Iwo Jima it was recommended that the Navajos be "thoroughly trained in a standard Navajo military dictionary."5 Quarterly training sessions were advised, in which messengers could review standard Navajo military code, as well as such duties as radio procedure and radio headings, to maintain a high degree of efficiency.

It is estimated that between 375 and 420 Navajos served as code talkers. The program was highly classified throughout the war and remained so until 1968. Though they returned home on buses without parades or fanfare and were sworn to secrecy about the existence of the code, the Navajo code talkers are now making their way into popular culture and mainstream American history.

Excerpts from the Navajo Code, Part 1; Folder 6, Box 5; History and Museums Division; Records Relating to Public Affairs; USMC Reserve and Historical Studies, 1942–1988; "C" Course to Wash. Daily News; Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, National Archives at College Park.

NAVAJO CODE: EXCERPTS English Letter Navaho Word Meaning A Wol-la-chee Ant B Shush Bear C Moasi cat D Be Deer E Dzeh Elk F Ma-e Fox G Klizzie Goat H Lin Horse I Tkin Ice J Tkele-cho-gi Jackass K Klizzie-yazzie Kid L Dibeh-yazzie Lamb M Na-as-tso-si Mouse N Nesh-chee Nut O Ne-ahs-jah Owl P Bi-so-dih Pig Q Ca-yeilth Quiver R Gah Rabbit S Dibeh Sheep T Than-zie Turkey U No-da-ih Ute V A-keh-di-glini Victor W Gloe-ih Weasel X Al-an-as-dzoh Cross Y Tsah-as-zih Yucca Z Besh-do-gliz Zinc English Word Navaho Word Meaning Corps Din-neh-ih Clan Switchboard Ya-ih-e-tih-ih Central Dive Bomber Gini Chicken Hawk Torpedo Plane Tas-chizzie Swallow Observation Plane Me-as-jah Owl Fighter plane Da-he-tih-hi Humming Bird Bomber Jay-sho Buzzard Alaska Beh-hga With-Winter America Ne-he-Mah Our Mother Australia Cha-yes-desi Rolled Hat Germany Besh-be-cha-he Iron Hat Philippines Ke-yah-da-na-lhe Floating Land NATIONAL ARCHIVES

WikipediaA code talker was a person employed by the military during wartime to use a little-known language as a means of secret communication. The term is most often used for United States service members during the World Wars who used their knowledge of Native American languages as a basis to transmit coded messages. In particular, there were approximately 400 to 500 Native Americans in the United States Marine Corps whose primary job was to transmit secret tactical messages. Code talkers transmitted messages over military telephone or radio communications nets using formally or informally developed codes built upon their Indigenous languages. The code talkers improved the speed of encryption and decryption of communications in front line operations during World War II and are credited with a number of decisive victories. Their code was never broken.There were two code types used during World War II. Type one codes were formally developed based on the languages of the Comanche, Hopi, Meskwaki, and Navajo peoples. They used words from their languages for each letter of the English alphabet. Messages could be encoded and decoded by using a simple substitution cipher where the ciphertext was the Native language word. Type two code was informal and directly translated from English into the Indigenous language. If there was no corresponding word in the Indigenous language for the military word, code talkers used short, descriptive phrases. For example, the Navajo did not have a word for submarine, so they translated it as iron fish.

Post War Recognition

The Navajo code talkers received no recognition until 1968 when their operation was declassified. In 1982, the code talkers were given a Certificate of Recognition by US President Ronald Reagan, who also named August 14, 1982 as Navajo Code Talkers Day.On December 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton signed Public Law 106–554, 114 Statute 2763, which awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the original 29 World War II Navajo code talkers and Silver Medals to each person who qualified as a Navajo code talker (approximately 300). In July 2001, President George W. Bush honored the code talkers by presenting the medals to four surviving original code talkers (the fifth living original code talker was unable to attend) at a ceremony held in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC. Gold medals were presented to the families of the deceased 24 original code talkers.

The Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 (Public Law 110–420) was signed into law by President George W. Bush on November 15, 2008. The act recognized every Native American code talker who served in the United States military during WWI or WWII (with the exception of the already-awarded Navajo) with a Congressional Gold Medal. The act was designed to be distinct for each tribe, with silver duplicates awarded to the individual code talkers or their next-of-kin. As of 2013, 33 tribes have been identified and been honored at a ceremony at Emancipation Hall at the US Capitol Visitor Center.

On November 27, 2017, three Navajo code talkers, joined by the President of the Navajo Nation, Russell Begaye, appeared with President Donald Trump in the Oval Office in an official White House ceremony. They were there to "pay tribute to the contributions of the young Native Americans recruited by the United States military to create top-secret coded messages used to communicate during World War II battles."