1920-1945

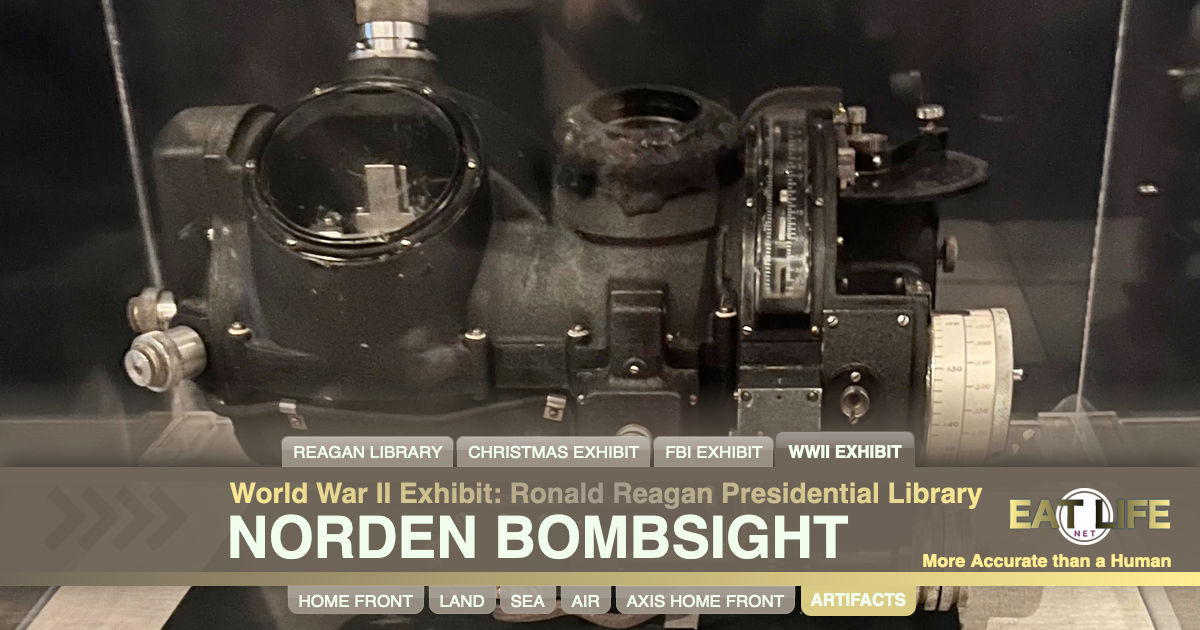

Dutch immigrant Carl Norden designed bombsights for the US Navy in the 1920s. It includes an analog computer that calculated the trajectory of the bomb, calculating crosswind, altitude, and airspeed, and then released the bomb. This computer was more accurate than a human bombardier, especially in high-altitude precision bombing from a plane moving over 300 feet per second.

National Park ServiceThe Second-Generation Norden Bombsight Vault

At the former McCook Army Air Base near McCook, Nebraska, is an example of the structures used by the military to help ensure the secrecy of this advanced technology device during World War II.The military quickly decided that strategic bombing would play an important role in the war. The Norden Bombsight was crucial in conducting that high-altitude precision strategic bombing by the U.S. Army Air Force and an essential factor in defining air war strategy. The sight was a highly accurate precision instrument developed by Carl L. Norden, a civilian consultant, and Captain Frederick I. Entwhistle, assistant research chief of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Ordnance. In 1932 the U.S. Army Air Corps ordered its own Norden bombsight.

Charles D. Bright described the sight in his Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Air Force:

Charles D. BrightPrecision bombing required meticulous control; to accomplish this, the Norden incorporated a gyrostabilized automatic pilot. The mechanism was modified in 1941 by the Minneapolis Honeywell Company and designated the Army C-1 autopilot. This modification enabled a bomber to be flown on a straight, level course, giving the bombardier a steady platform on which to operate the bombsight during the bombing run. Also known as the "Blue Ox" the Norden could quickly calculate and correct directional changes due to wind drift. Flying at a preset altitude, it could rapidly compute the correct bomb release angle for a constant speed of closure to the aiming point. Under optimal conditions on an undisturbed run, the accuracy of the device was excellent. However, any last second changes in the altitude of the bomber, such as those encountered during battle, could markedly influence the accuracy of the sight.Because of the importance and sensitive nature of the technology, the Norden Bombsight was a closely guarded secret that required a secure area for its storage when not in use for training. Originally, Norden Bombsights were stored in a wooden building that contained five or six concrete vaults, as well as an area to test and repair the sights.

After the Norden Bombsight was reclassified from secret to restricted (probably in 1943), second-generation bombsight vaults came into use. The second-generation vault stood in the open and was used solely for storage purposes. The second-generation Norden Bombsight vault at the former McCook Army Air Field is a small rectangular structure, one-story in height, 11 feet wide and 13 feet deep. It has a very slightly sloping shed-roof and one door on the main façade. The walls are 8 inches thick and the roof is also of reinforced concrete with a tar membrane. An L-shaped wing that measures five feet 10 inches by six feet eight inches is located on the southeast façade, and also has a shed-roof and a door on the main façade. Its function is unknown, though it may have housed electrical equipment. Surrounding the bombsight vault is a combination two-strand barbed wire and six-by-six woven-wire fence, supported by wooden posts. Divided into 10-foot sections, the fence extends 50 feet on each side except in the front where a 10-foot gap provides an entryway.

WIKIPEDIAThe Norden Mk. XV

Norden M Series

Bombsight that was used by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) and the United States Navy during World War II, and the United States Air Force in the Korean and the Vietnam Wars. It was an early tachometric design that directly measured the aircraft's ground speed and direction, which older bombsights could only estimate with lengthy manual procedures. The Norden further improved on older designs by using an analog computer that continuously recalculated the bomb's impact point based on changing flight conditions, and an autopilot that reacted quickly and accurately to changes in the wind or other effects. Together, these features promised unprecedented accuracy for daytime bombing from high altitudes.During prewar testing the Norden demonstrated a circular error probable (CEP) of 75 feet, an astonishing performance for that period. This precision would enable direct attacks on ships, factories, and other point targets. Both the Navy and the USAAF saw it as a means to conduct successful high-altitude bombing. For example, an invasion fleet could be destroyed long before it could reach U.S. shores.

To protect these advantages, the Norden was granted the utmost secrecy well into the war, and was part of a production effort on a similar scale to the Manhattan Project: the overall cost (both R&D and production) was $1.1 billion, as much as 2/3 of the latter or over a quarter of the production cost of all B-17 bombers. The Norden was not as secret as believed; both the British SABS and German Lotfernrohr 7 worked on similar principles, and details of the Norden had been passed to Germany even before the war started.

Under combat conditions the Norden did not achieve its expected precision, yielding an average CEP in 1943 of 1,200 feet (a CEP of 1200 feet means 50% of all bombs dropped land within 1200 feet of the target), similar to other Allied and German results. Both the Navy and Air Forces had to give up using pinpoint attacks. The Navy turned to dive bombing and skip bombing to attack ships, while the Air Forces developed the lead bomber procedure to improve accuracy, and adopted area bombing techniques for ever-larger groups of aircraft. Nevertheless, the Norden's reputation as a pin-point device endured, due in no small part to Norden's own advertising of the device after secrecy was reduced late in the war.

The Norden saw reduced use in the post–World War II period after radar-based targeting was introduced, but the need for accurate daytime attacks kept it in service, especially during the Korean War. The last combat use of the Norden was in the U.S. Navy's VO-67 squadron, which used it to drop sensors onto the Ho Chi Minh Trail in 1967. The Norden remains one of the best-known bombsights.