How a Deck of Cards and Monopoly helped Save POWs

British and US Airmen flying missions in enemy airspace were always in danger of being shot out of the sky, finding themselves trapped behind enemy lines with no idea where they were. Escape maps, printed on lightweight fabric, were issued to them to guide them back to safety over unfamiliar territory. They were able to be concealed in jacket linings, boots, or even cigarette packages, but wouldn't tear or run in water. They also wouldn't make a crinkle sound or rustle when folded. Some pilots did not make it out safely and were captured by enemy forces. Other servicemen were also captured and held as POWs.

In Germany, they were held in prison camps called Stalags. Enlisted and officers were kept in separate camps. A welcome sight in these camps were the care packages sent by humanitarian groups like the Red Cross. Governments also set up fake charities with innocuous names like the "Licensed Victuallers Prisoners Relief Fund." There would be food, cigarettes, and toiletry items inside the boxes. But they also held secrets.

The US government and the United States Playing Card Company collaborated on a special series of Bicycle-brand cards. Cards were not confiscated from downed pilots and sent in the care packages. These special decks of cards had escape maps printed on the sheet before the faces were laid over it and the sheets were cut into the individual cards. The required federal revenue stamp on the box was slightly crooked, a clue that the deck was "special." When the cards were moistened, the face was able to be peeled away, revealing the map behind it. The cards were laid to reconstitute the full picture.

RAF airmen were told to look for "special edition" Monopoly sets in their packages if they were captured. The only difference between these and the regular versions was a red dot on the Free Parking space. The UK government, specifically MI9, the British secret-service unit responsible for escape and evasion, worked with John Waddington, Ltd. to make a clandestine version of Monopoly. Inside the boards were escape maps printed on silk. Metal files and magnetic compasses were disguised as playing pleces. Mixed in with Monopoly Money was genuine French, German and Italian currency. Once the tools of escape were pocketed or hidden, POWs were instructed to destroy the games.

1944-1945

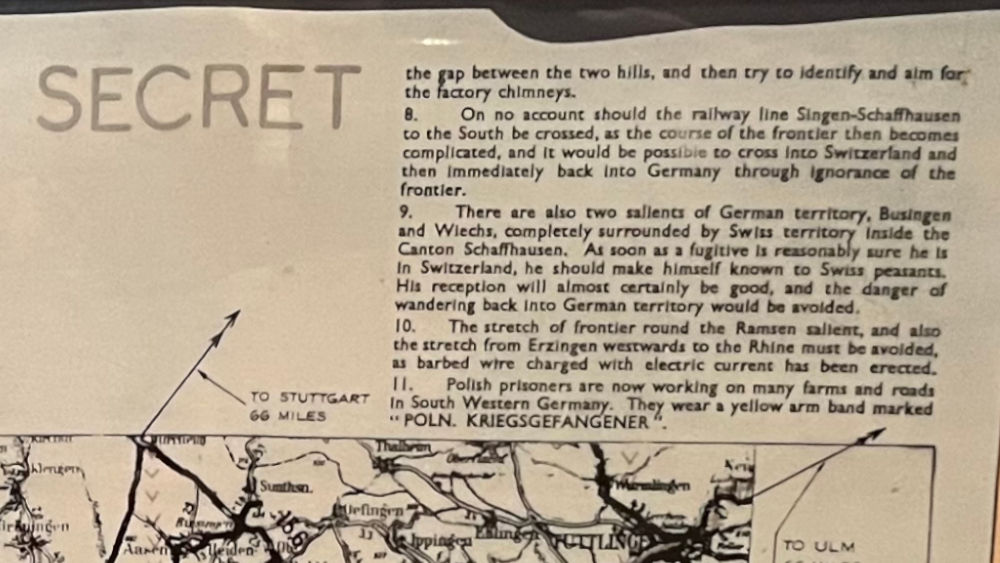

Maps printed on silk and other types of cloth were issued to pilots and anyone on missions behind enemy lines, or smuggled in POW care packages. Lightweight but durable and easy to conceal, they provided Allied troops and POWs escape routes through unfamiliar terrain.

During WWII Air Crews were supplied with a deck of cards. In the event that our men were captured and put in prisoner of war camps, the guards would let them keep the cards. They figured it would keep therm occupied. They didn't know that if a prisoner managed to escape, that the face of the cards could be peeled off to uncover their escape route back to our lines. See the back of these cards.

This is a Replica Deck of Cards Escape Map

During World War II thousands of U.S. airmen were shot down over Europe and became prisoners of war (POW's).

Many tried to escape the POW camps, and some succeeded.

For a successful escape, a prisoner had to know where he was, and how to get to safe or neutral territory.

He needed a map. This is a replica of a little-known means of providing such a map.

Decks of cards were printed with a map on the front side and the face of the cards was glued on top of of this map. The deck was then cut, boxed and mailed to the POW camp, along with regular cards and letters. The required federal revenue stamp on the box was slightly crooked, a clue that the deck was "special". The deck was set aside from others received and then soaked in water. The face of the cards was peeled off and the map was assembled.

Different Luftwaffe POW camps (Stalag Lufts) had different maps. The map on display here is for the territory around Stalag Luft 3, site of "The Great Escape" which was dramatized in the motion picture of the same name.

Imagine it's 1942, and you're a member of Britain's Royal Air Force. In a skirmish above Germany, your plane was shot out of the sky, and since then you've been hunkered down in a Prisoner of War camp. Your officers have told you it's your duty to escape as soon as you can, but you can't quite figure out how-you've got no tools and no spare rations, and you don't even know where you are.How Millions Of Secret Silk Maps Helped POWs Escape Their Captors in WWII

The ingenious maps played a role in some 750 successful escapes.One day, though, you're playing Monopoly with your fellow prisoners when you notice a strange seam in the board. You pry it open-and find a secret compartment with a file inside. In other compartments, other surprises: a compass, a wire saw, and a map, printed on luxurious, easily foldable silk and showing you exactly where you are, and where safety is. You've received a package from Christopher Clayton Hutton - which means you're set to go.

Over his six-year tenure as Technical Officer to the Escape Department, he would invent dozens of vital gizmos: ration packs squirreled into cigar boxes, miniature compasses hidden in buttons and cuff links, cigarette holders that doubled as tiny telescopes. But his first order of business was maps. In particular, he wanted to create maps to be included in "escape kits."

These maps would need to be thin enough to be snuck into a boot or coat lining, durable enough to survive wear and tear in the field-but detailed enough that escaping soldiers could use them to find their way through unfamiliar terrain.

Now he just needed to figure out what to print the maps on. The necessary material had to fit a number of criteria: "It had to be so thin that it would take up next to no room when folded, and at the same time it had to be fairly durable and crease-resisting," Hutton wrote. It also had to be waterproof, easy to print on, and easy to read-and most importantly, when secreted within a flak jacket or combat boot, it couldn't rustle and give itself away.

Hutton talked to paper manufacturers across London, but none of their offerings worked out. The heavy papers were far too loud, revealing themselves at the slightest prodding. The thin papers-"no thicker than that of the finest toilet roll," Hutton wrote-were prone to disintegration. So Hutton turned to another substrate: silk.

After days of messy experimentation with different printing materials and methods, he came up with an ink-and-pectin mixture that sat perfectly on the silk's surface. Soon, his suppliers were churning out maps by the thousands, with frontiers, demarcation lines, and other vital information clearly marked.

Hutton's next challenge was figuring out how the silk and mulberry leaf maps could be carried in a clandestine way. For soldiers not yet deployed, Hutton did as much as he could with flight boots: a silk map and compass were stuffed into cavity in the heel, a small knife was tucked into the cloth loop, and a long, thin wire saw was threaded into the laces. An escaping fighter could use the knife or saw to cut the boots' tops off, transforming them into much less conspicuous "civilian shoes."

But the fighters who needed the maps most-those who had already been captured-were trickier to access. Hutton came up with a plan for that, too. Thanks to the Geneva Convention, prisoners of war were allowed to receive packages from their families and other aid organizations. Parcels that contained games, sports equipment, and other fun pursuits were especially encouraged-not only by the POWs themselves, but by their captors, who figured hobbies would keep bored prisoners out of trouble.

WIKIPEDIAEvasion Charts or Escape Maps

Maps made for servicemembers, and intended to be used when caught behind enemy lines to assist in performing escape and evasion. Such documents were secreted to prisoners of war by various means to aid in escape attempts.During World War II, these clandestine maps were used by many American, British, and allied servicemen to escape from behind enemy lines. Special material was used for this purpose, due to the need for a material that would be hardier than paper, and would not tear or dissolve in water.

During WWII hundreds of thousands of maps were produced by the British on thin cloth and tissue paper. The idea was that a serviceman captured or shot down behind enemy lines should have a map to help him find his way to safety if he escaped or, better still, evade capture in the first place. Many of these maps were also used in clandestine wartime activities.

The cloth maps were sometimes hidden in special editions of the Monopoly board game sets sent to the prisoners of war camps. The marked game sets also included foreign currency (French and German, for example), compasses and other items needed for escaping Allied prisoners of war. Escape maps were also printed on playing cards distributed to Prisoners of War which could be soaked and peeled apart revealing the escape map. Other maps were hidden inside spools of cotton thread in sewing kits. Due to the inherent strength and extremely compact nature of the MI9 mulberry leaf tissue maps, they could be wound into twine and then rolled into the core of cotton reels.

Twitter1942

The @USPCC teamed up with US military forces during WWII to create @bicyclecards decks for POWs. The best part? The cards pulled apart to reveal secret maps that could help them escape German camps.

Stacking the Deck:

Escape Cards of World War II

During World War II, American and British intelligence agencies collaborated on a top-secret mission with the US Playing Card Company. To help Allied prisoners of war escape from Nazi prison camps, the company devised a way to hide a map of Germany inside playing cards.National Park ServiceWorld War II

Nazi Germany captured and detained nearly 94,000 prisoners of war (POWs) from the United States.[1] POWs from the US and other Allied nations were imprisoned at Prisoner of War Camps throughout Europe, including Stalag Luft III in western Poland and Oflag IV-C in eastern Germany.To facilitate escape attempts, the American Office of Strategic Services (precursor to the CIA) and British Special Operations Executive hatched a plan. They tasked the United States Playing Card Company (USPCC) to create decks of Bicycle brand playing cards that could conceal maps of Germany.[3]

Under the rules of the Geneva Conventions, the Red Cross and other charitable organizations could send parcels and mail to prisoners of war.[4] In addition to clothing, food, medical supplies, and tobacco, parcels could contain games, such as playing cards. If Allied POWs were lucky, an enclosed deck of cards would offer more than just a way to keep busy.

All Bicycle decks had the same white and blue design, but a crooked cellophane seal on the box indicated that there was more than met the eye. When the cards were wet, POWs could peel apart the layers of paper, revealing pieces of a large map. Once the cards were arranged in order, the map outlined escape routes out of Germany.[5] Other cards contained instructions about places to avoid or landmarks to look out for.

Based in Norwood, Ohio (an enclave of Cincinnati), the US Playing Card Company Complex had already converted much of its production lines to wartime uses. The company churned out parachutes for antipersonnel fragmentation bombs.[6] Other products included materials for defense, as well as electronics and radar devices for the Navy and Signal Corps. During World War II, the USPCC produced another special deck of cards printed with the shapes of military vehicles from other warring countries. Known as "spotter decks," these cards were intended to help civilians identify ships, tanks, and aircraft from both friendly and enemy nations.

Due to the top-secret nature of the map decks, the project had to remain confidential for many years after the war. It is unknown how many escape map decks were produced or survived. Only two full decks are still known to exist. They are both held in the collection of the International Spy Museum in Washington, DC.