PBSWorker Shortage

In early 1942, the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicted a big problem: Unless action was taken, a shortage of six million workers would bring the country's productivity to a halt by the end of 1943. Just months after the United States formally entered World War II, American men were leaving for active duty overseas, and it was critical to prevent interruptions to industry. The solution was as clear as the problem. "With the exception of the few hundred thousand boys of predraft age," a government study stated, "this gap will have to be plugged almost entirely by women."President Roosevelt tasked the Office of War Information, a newly formed federal propaganda agency, with selling the idea of women workers to the country. "These jobs will have to be glorified as a patriotic war service if American women are to be persuaded to take them and stick to them," said an OWI report. "Their importance to a nation engaged in total war must be convincingly presented. Joining the government's effort were private industry and the American media, who together generated some of the era's most enduring and well-known images.

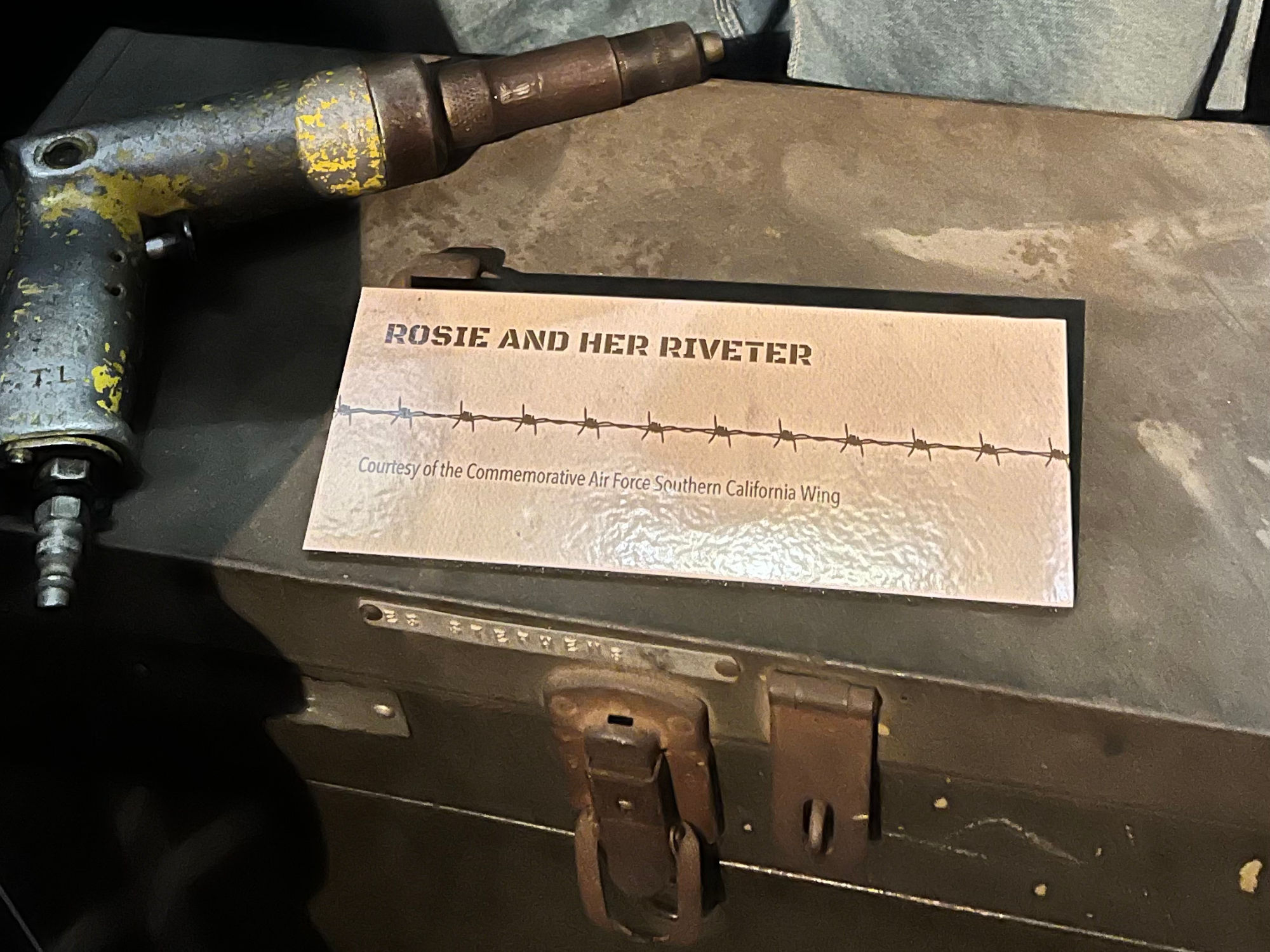

Late in 1942, Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller produced a painting for the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. The image of a female worker in denim coveralls and a red-and-white polka-dot headscarf, with a Westinghouse employee identification badge pinned to her lapel, was reproduced on posters for display inside the company's munitions factories. Miller's image had a limited and largely private run, appearing on Westinghouse shop floors over a two-week period from February 15-28, 1943, before the company tacked up the next in a series of his paintings. Like the "We Can Do It!" poster, below, each painting bore a different message intended to increase production, boost morale, avoid absenteeism or prevent strikes. Beyond the Westinghouse factory walls, however, the bandanned woman remained unknown. Miller's subject was also unnamed, but not for long.

Also in February 1943, a song written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb and sung by The Four Vagabonds hit the American radio airwaves. "Rosie the Riveter" told a story happening across the country: Women were going to work in record numbers, doing jobs unlike those they had ever done. "All the day long, whether rain or shine," the lyrics went, "she's part of the assembly line/She's making history, working for victory/Rosie the riveter." According to Loeb's widow, no single woman inspired the song; the name Rosie was chosen for its alliterative appeal. In the naming, though, an American archetype was born.

By the time artist Norman Rockwell painted what became the Saturday Evening Post's May 29, 1943 cover, Rosie was a well-known character; a hard-working, patriotic woman. On her lunch break from the assembly line, she sits denim clad with a rivet gun on her lap. To complete his composition-which Rockwell said was based on Michaelangelo's Sistine Chapel painting of the prophet Isaiah-Rosie stood atop a copy of Mein Kampf, so stamping out fascism with her own might. The U.S. Treasury Department's subsequent use of Rockwell's art to advertise war bonds ensured that his was the image Americans would identify with Rosie the Riveter throughout the war.

History.comRosie the Riveter

She was the star of a campaign aimed at recruiting female workers for defense industries during World War II, and she became perhaps the most iconic image of working women. American women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers during the war, as widespread male enlistment left gaping holes in the industrial labor force. Between 1940 and 1945, the female percentage of the U.S. workforce increased from 27 percent to nearly 37 percent, and by 1945 nearly one out of every four married women worked outside the home.While women during World War II worked in a variety of positions previously closed to them, the aviation industry saw the greatest increase in female workers.

More than 310,000 women worked in the U.S. aircraft industry in 1943, making up 65 percent of the industry's total workforce (compared to just 1 percent in the pre-war years). The munitions industry also heavily recruited women workers, as illustrated by the U.S. government's Rosie the Riveter propaganda campaign.

Based in small part on a real-life munitions worker, but primarily a fictitious character, the strong, bandanna-clad Rosie became one of the most successful recruitment tools in American history, and the most iconic image of working women in the World War II era.

In movies, newspapers, propaganda posters, photographs and articles, the Rosie the Riveter campaign stressed the patriotic need for women to enter the workforce. On May 29, 1943, The Saturday Evening Post published a cover image by the artist Norman Rockwell, portraying Rosie with a flag in the background and a copy of Adolf Hitler's racist tract "Mein Kampf" under her feet.

Though Rockwell's image may be a commonly known version of Rosie the Riveter, her prototype was actually created in 1942 by a Pittsburgh artist named J. Howard Miller, and was featured on a poster for Westinghouse Electric Corporation under the headline "We Can Do It!"

Early in 1943, a popular song debuted called "Rosie the Riveter," written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb, and the name went down in history.

Rosie The RiveterWorkplace Changed Forever

The call for women to join the workforce during World War II was meant to be temporary and women were expected to leave their jobs after the war ended and men came home. The women who did stay in the workforce continued to be paid less than their male peers and were usually demoted. But after their selfless efforts during World War II, men could no longer claim superiority over women. Women had enjoyed and even thrived on a taste of financial and personal freedom-and many wanted more. The impact of World War II on women changed the workplace forever, and women's roles continued to expand in the postwar era.

Research Guides

Rosie the Riveter:

Working Women and World War II

The female icon of World War II "Rosie the Riveter" depicted women workers during World War II. This research guide serves as an introduction to primary and secondary resources on this subject both at the Library of Congress and on the Web.Library of CongressRosie the Riveter

The female icon of World War II

The character of "Rosie the Riveter" first began as a song inspired by war worker Rosalind P. Walter. After high school, 19 year old Rosalind began working as a riveter on Corsair fighter planes at the Vought Aircraft Company in Stratford, Connecticut. After a newspaper article featuring Rosalind's work was published, songwriters Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb were inspired to write the song "Rosie the Riveter." With the release of this song, the concept of Rosie the Riveter became a part of public consciousness.It should be noted that while Rosalind may have been the first, there were many other "real life Rosies" throughout the war. Rosie the Riveter came to be a symbol of all women working in the war industries during World War II. After the release of the song inspired by Rosalind, the image of Rosie the Riveter became further cemented in the public imagination in large part due to the circulation of illustrations and propaganda. On May 29, 1943, the Norman Rockwell Rosie illustration was published on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post. Today, perhaps the most famous of all the Rosie imagery is "We Can Do It," created by J. Howard Miller and published by Westinghouse. Surprisingly, "We Can Do It" was not widely circulated during the war years, and there is no evidence to suggest that it was ever seen outside of the Westinghouse factory floors. The popularity of "We Can Do It" is largely attributed to its inclusion in a 1982 Washington Post Magazine article, "Poster Art for Patriotism's Sake," about the poster collections at the National Archives.

Transcript of video presentation by Sheridan HarveyRosie the Riveter is the female icon of Word War II. She is the home-front equivalent of G.I. Joe. She represents any woman defense worker. And for many women, she's an example of a strong, competent foremother.

Many of us have an image in our minds when we hear "Rosie the Riveter." Don't you? The woman in the bandanna rolling up the sleeve on her raised bent arm.

The artist Norman Rockwell is closely associated with Rosie, but how many of you have heard of J. Howard Miller? Yet it was Miller who created this image.

I found something unexpected when I turned to Norman Rockwell's Rosie. It appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post on May 29, 1943--the Memorial Day issue. This was not the tidy image in my mind. This Rosie is brawny and larger-than-life.

In my surprise at the two images, I decided to look into the development of the myth of Rosie the Riveter.

The chronology isn't always clear, but it seems that about 1942, an artist at Westinghouse named J. Howard Miller created "We Can Do It!," probably as part of his company's war work. The federal government encouraged industries to try to get more people to go to work. "We Can Do It!" initially had no connection with someone named Rosie.

The next step in the Rosie myth was apparently the song "Rosie the Riveter" by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb, released in early 1943.

Some of the lyrics go:

All the day long,

Whether rain or shine,

She's a part of the assembly line.

She's making history,

Working for victory,

Rosie the Riveter.

Keeps a sharp lookout for sabotage,

Sitting up there on the fuselage.

That little girl will do more than a male will do.And skipping to the end:

There's something true about,

Red, white, and blue about,

Rosie the Riveter.So you have this song appearing in early 1943. Then a few months later on May 29th you get the Rockwell cover.

It seems likely that Rockwell had heard the song, since he wrote the name "Rosie" on the lunch box in his picture.

This was a big boost to the Rosie story. In the 1940s the circulation of the Saturday Evening Post was about four million. And when a Rockwell drawing was going to be on the cover, they published extra issues. He was the most popular illustrator in the country.

WIKIPEDIARosie the Riveter

Allegorical cultural icon in the United States who represents the women who worked in factories and shipyards during World War II, many of whom produced munitions and war supplies. These women sometimes took entirely new jobs replacing the male workers who joined the military. She is widely recognized in the "We Can Do It!" poster as a symbol of American feminism and women's economic advantage.The idea of Rosie the Riveter originated in a song written in 1942 by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb. Images of women workers were widespread in the media in formats such as government posters, and commercial advertising was heavily used by the government to encourage women to volunteer for wartime service in factories.

The Song

The term "Rosie the Riveter" was first used in 1942 in a song of the same name written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb. The song was recorded by numerous artists, including the popular big band leader Kay Kyser, and it became a national hit. It was also recorded by the R&B group, The Four Vagabonds. The song portrays "Rosie" as a tireless assembly line worker, who earned a "Production E" doing her part to help the American war effort.

The Westinghouse Poster

In 1942, Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller was hired by the Westinghouse Company's War Production Coordinating Committee to create a series of posters for the war effort. One of these posters became the famous "We Can Do It!" image, an image that in later years would also be called "Rosie the Riveter" although it had never been given that title during the war. The "We Can Do It!" poster was displayed only to Westinghouse employees in the Midwest during a two-week period in February 1943, then it disappeared for nearly four decades.During the war, the name "Rosie" was not associated with the image, and the purpose of the poster was not to recruit women workers but to be motivational propaganda aimed at workers of both sexes already employed at Westinghouse. It was only later, in the early 1980s, that the Miller poster was rediscovered and became famous, associated with feminism, and often mistakenly called "Rosie the Riveter".

The Saturday Evening Post Cover

Norman Rockwell's image of "Rosie the Riveter" received mass distribution on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on Memorial Day, May 29, 1943. Rockwell's illustration features a brawny woman taking her lunch break with a rivet gun on her lap and beneath her penny loafer a copy of Adolf Hitler's manifesto, Mein Kampf. Her lunch box reads "Rosie"; viewers quickly recognized that to be "Rosie the Riveter" from the familiar song.Rockwell, America's best-known popular illustrator of the day, based the pose of his 'Rosie' on that of Michelangelo's 1509 painting Prophet Isaiah from the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Rosie is holding a ham sandwich in her left hand, and her blue overalls are adorned with badges and buttons: a Red Cross blood donor button, a white "V for Victory" button, a Blue Star Mothers pin, an Army-Navy E Service production award pin, two bronze civilian service awards, and her personal identity badge.