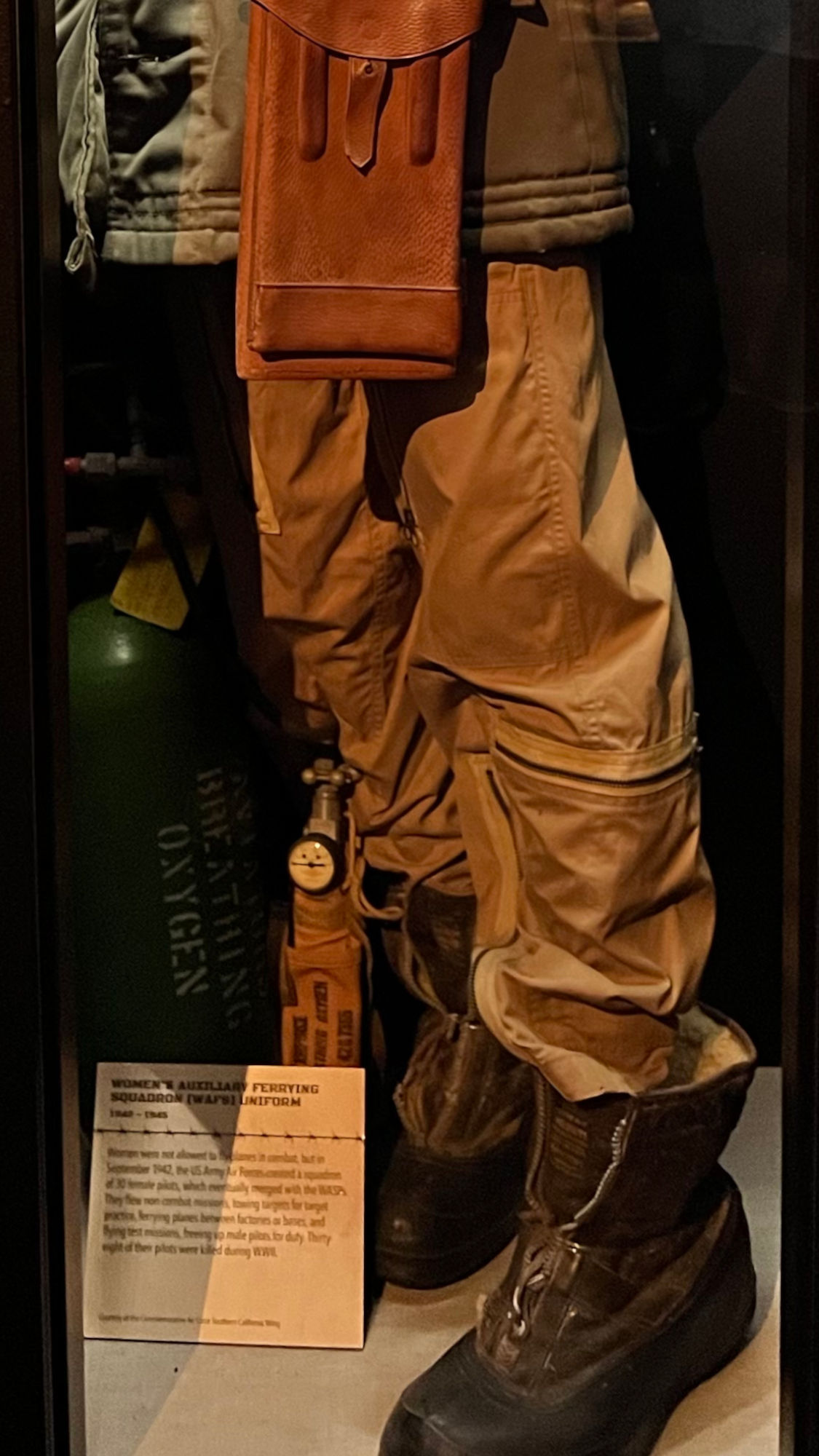

1942-1945

Women were not allowed to fly planes in combat, but in September 1942, the US Army Air Forces created a squadron of 30 female pilots, which eventually merged with the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs).

They flew non-combat missions, towing targets for target practice, ferrying planes between factories or bases, and flying test missions, freeing up male pilots for duty. Thirty-eight of their pilots were killed during WWII.

National ArchivesThe Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS/WASP)

In September 1942, the Army Air Force (AAF) created the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) and appointed Nancy H. Love its commander. Love recruited highly skilled and experienced female pilots who were sent on noncombat missions ferrying planes between factories and AAF installations.While WAFS was being organized, the Army Air Force appointed Jacqueline Cochran as Director of Women's Flying Training. Cochran's school, which eventually moved to Avenger Field in Sweetwater, TX, trained 232 women before it ceased operations. Eventually, over 1000 women completed flight training. As the ranks of women pilots serving the AAF swelled, the value of their contribution began to be recognized, and the Air Force took steps to militarize them. As a first step the Air Force renamed their unit from WAFS to Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).

Although not allowed to fly combat missions, WAFS/WASP pilots served grueling, often dangerous, tours of duty. Ferrying and towing were risky activities, and some WAFS/WASP pilots suffered injuries and were killed in the course of duty. In 1977, after much lobbying of Congress, the WASP finally achieved military active duty status for their service.

I knew I was going to join the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron before the organization was a reality, before it had a name, before it was anything but a radical idea in the minds of a few men who believed that women could fly airplanes. But I never knew it so surely as I did in Honolulu on December 7, 1941.At dawn that morning I drove from Waikiki to the John Rodgers civilian airport right next to Pearl Harbor where I was a [ill.] pilot instructor. Shortly after six-thirty I began landing and take-off practice with my regular student. Coming in just before the last landing, I looked casually around and saw a military plane coming directly toward me. I jerked the controls away from my student and jammed the throttle wide open to pull above the oncoming plane. He passed so close under us that our celluloid windows rattled violently and I looked down to see what kind of plane it was.

The painted red balls on the tops of the wings shone brightly in the sun. I looked again with complete and utter disbelief. Honolulu was familiar with the emblem of the Rising Sun on passenger ships but not on airplanes.

I looked quickly at Pearl Harbor and my spine tingled when I saw billowing black smoke. Still I thought hollowly it might be some kind of coincidence or maneuvers, it might be, it must be. For surely, dear God...

Then I looked way up and saw the formations of silver bombers riding in. Something detached itself from an airplane and came glistening down. My eyes followed it down, down and even with knowledge pounding in my mind, my heart turned convulsively when the bomb exploded in the middles of the harbor. I knew the air was not the place for my little baby airplane and I set about landing as quickly as ever I could. A few seconds later a shadow passed over me and simultaneously bullets spattered all around me.

Suddenly that little wedge of sky above Hickam Field and Pearl Harbor was the busiest fullest pieces of sky I ever saw.

We counted anxiously as our little civilian planes came flying home to roost. Two never came back. They were washed ashore weeks later on the windward side of the island, bullet-riddled. Not a pretty way for the brave little yellow Cubs and their pilots to go down to death.

The rest of December seventh has been described by too many in too much detail for me to reiterate. I remained on the island until three months later when I returned by convoy to the United States. None of the pilots wanted to leave but there was no civilian flying in the islands after the attack. And each of us had some indication [ill.] brought murder and destruction to our islands.

When I returned, the only way I could fly at all was to instruct Civilian Pilot Training programs. Weeks passed. Then, out of the blue, came a telegram from the War Department announcing the organization of the WAFS (Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron) and the order to report within twenty-four hours if interested. I left at once.

Mrs. Nancy Love was appointed Senior Squadron Leader of the WAFS by the Secretary of War. No better choice could have been made. First and most important she is a good pilot, has tremendous enthusiasm and belief in women pilots and did a wonderful job in helping us to be accepted on an equal status with men.

WIKIPEDIAThe Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP)

Women's Army Service Pilots

Women's Auxiliary Service Pilots

a civilian women pilots' organization, whose members were United States federal civil service employees. Members of WASP became trained pilots who tested aircraft, ferried aircraft, and trained other pilots. Their purpose was to free male pilots for combat roles during World War II. Despite various members of the armed forces being involved in the creation of the program, the WASP and its members had no military standing.The WASP arrangement with the US Army Air Forces ended on December 20, 1944. During its period of operation, each member's service had freed a male pilot for military combat or other duties. They flew over 60 million miles; transported every type of military aircraft; towed targets for live anti-aircraft gun practice; simulated strafing missions and transported cargo. Thirty-eight WASP members died during these duties and one, Gertrude Tompkins, disappeared while on a ferry mission, her fate still unknown. In 1977, for their World War II service, the members were granted veteran status, and in 2009 awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.

Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS)

Nancy Harkness Love's husband, Robert Love, was part of the Army Air Corps Reserve and worked for Colonel William H. Tunner. When Robert Love mentioned that his wife was a pilot, Tunner became interested in whether she knew other women who were pilots. Tunner and Nancy Love met and began to plan an aviation ferrying program involving women pilots. More formally, on June 11, 1942, Colonel Tunner suggested putting women pilots into the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). However, there were technical problems with this suggestion, so it was decided to pursue hiring civilian pilots for the ATC instead. By June 18, Love had drafted a plan to send to General Harold L. George who sent the proposal onto General Henry H. Arnold. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about women working as pilots during the war in her September 1 "My Day" newspaper column, supporting the idea. General George again broached the idea with General Arnold, who finally, on September 5, directed that "immediate action be taken and the recruiting of women pilots begin within twenty-four hours." Nancy Harkness Love was to be the director of the group and she sent out 83 telegrams to prospective women pilots that same day.The Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) went into operation publicly on September 10, 1942. Soon, the Air Transport Command began using women to ferry planes from factory to airfields. Love started with 28 women pilots, but they grew in number during the war until there were several squadrons. Requirements for recruits were that they had to be between ages 21 and 35, have a high school diploma, a commercial flying license, 200 horsepower engine rating, 500 hours of flight time and experience in flying across the country.

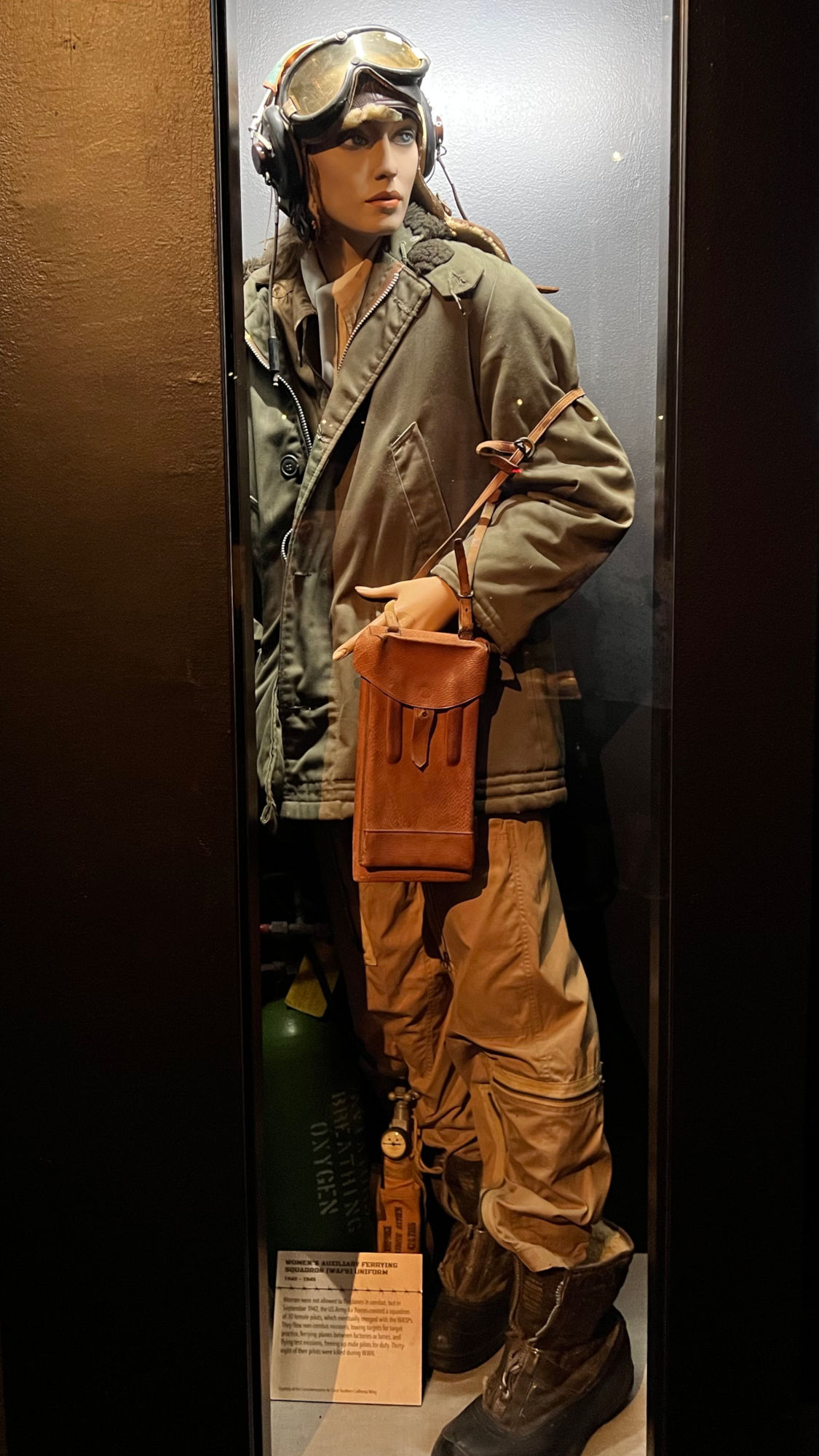

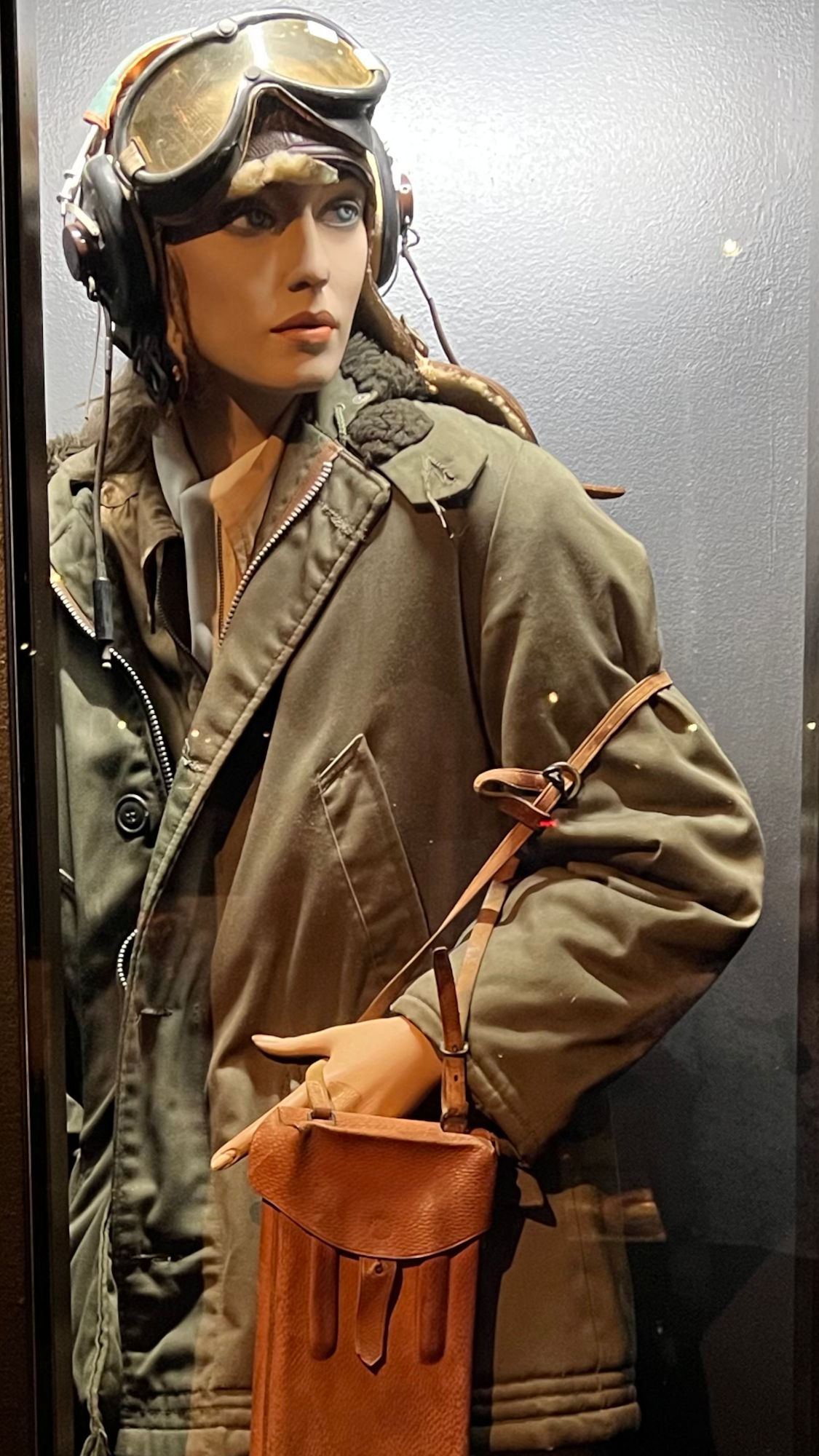

WIKIPEDIAUniforms for the WAFS

Designed by Love and consisted of a gray gabardine jacket with brass buttons and square shoulders. The uniform could be worn with gored skirts or slacks also made of gabardine. Because they had to pay for their own uniforms, only 40 women ever wore the WAFS uniform. All WAFS were issued a flight uniform of khaki flight coveralls, a parachute, goggles, a flying scarf and leather flying jacket sporting the ATC patch.Headquarters for WAFS was established at the new (May 1943) New Castle Army Air Base (the former Wilmington Airport). Tunner ensured that there were quarters for the women to live in at the base.

WAFS worked under a 90 day, renewable contract. WAFS earned $250 a month and had to provide and pay for their own room and board.

The first group of WAFS recruits were known as the Originals. Betty Gillies was the first woman to show up for training. On October 6, Gillies was made an executive officer and second-in-command of the WAFS. Gillies was familiar with drill and command techniques which she had learned at finishing school. The first WAFS assignment was run by Gillies on October 22, 1942. Six WAFS would ferry six L-4B Cubs from the factory to Mitchel Field. The original squadron of 28 was reduced to 27 when Pat Rhonie left on December 31 after disagreeing with Colonel Baker.

The WAFS each had an average of about 1,400 flying hours and a commercial pilot rating. They received 30 days of orientation to learn Army paperwork and to fly by military regulations. Afterward, they were assigned to various ferrying commands. At the beginning of 1943, three new squadrons were formed. The 4th Ferrying Group was in Romulus and commanded by Del Scharr. The 5th Ferrying Group was stationed at Love Field and was under the command of Florene Miller. The 6th Ferrying Group was stationed at Long Beach and commanded by Barbara Jane Erickson.