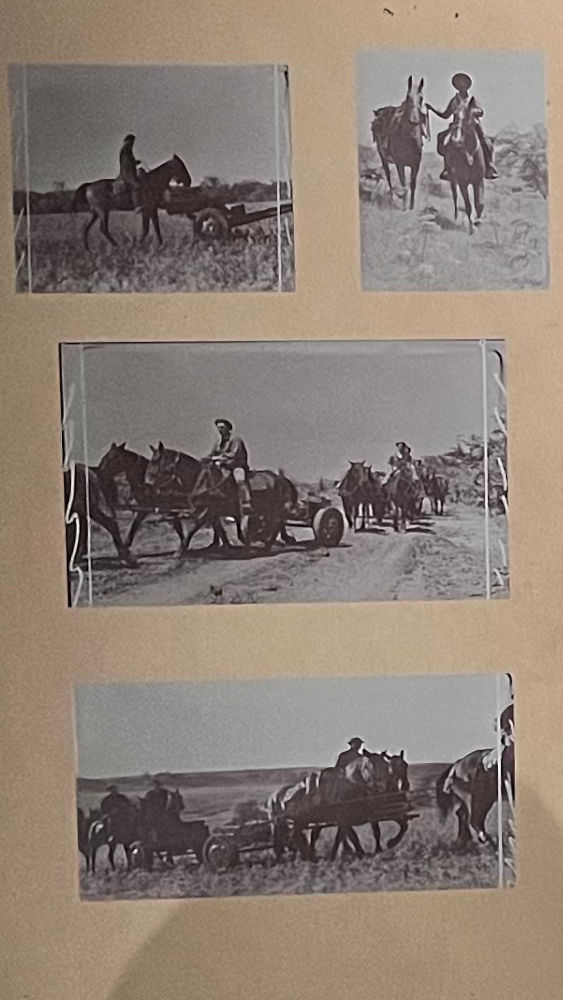

At the onset of WWII, the United States Army had thousands of horses and mules in various support roles. Horses were used for transportation of troops, artillery, materiel, messages, and to a lesser extent, in mobile cavalry troops. The Army, however, quickly became aware that mechanized units were necessary replaced horses with jeeps and tanks. The office of Chief of Cavalry was eliminated by March 1942.

Horses and Mules in WWII

At the onset of WWII, the United States Army had thousands of horses and mules in various support roles and in 1941, Life magazine reported that the US Army was buying 20,000 horses. In fact, according to the magazine, it was the biggest order for horses the army had placed since the Civil War.

The Army, however, quickly became aware that mechanized units were necessary and the office of Chief of Cavalry was eliminated by March 1942. Newly formed ground force units began mechanization of the remaining horse units, replacing horses with jeeps and tanks.

The Army 10th Light Division (Alpine), later the 10th Mountain, was originally formed in WWI.

It was activated on July 15, 1943 at Camp Hale, CO.

They included a mounted reconnaissance (recon) troop using a combination of horses, pack mules, and skis and snowshoes in order to perform reconnaissance in winter conditions.

However, it was thought this was not tactically viable and mounted troops were transferred to other roles throughout the division.

When the 10th arrived in Italy, it quickly became apparent that mounted recon were well suited to the rugged mountain terrain.

Horses were able to travel areas that even the best off-road mechanized vehicles could not.

They quickly reconstituted mounted recon troops from volunteers who had previously been trained with the cavalry.

They were equipped with pack transportation saddles and tack and Italian horses.

The Army 10th Light Division (Alpine), later the 10th Mountain, was originally formed in WWI.

It was activated on July 15, 1943 at Camp Hale, CO.

They included a mounted reconnaissance (recon) troop using a combination of horses, pack mules, and skis and snowshoes in order to perform reconnaissance in winter conditions.

However, it was thought this was not tactically viable and mounted troops were transferred to other roles throughout the division.

When the 10th arrived in Italy, it quickly became apparent that mounted recon were well suited to the rugged mountain terrain.

Horses were able to travel areas that even the best off-road mechanized vehicles could not.

They quickly reconstituted mounted recon troops from volunteers who had previously been trained with the cavalry.

They were equipped with pack transportation saddles and tack and Italian horses.

The Soviets and the Germans were the most dependent on horses during WWII, but the Italian, Japanese, Polish, and Romanian armies also continued to employ substantial cavalry formations.

- The Polish cavalry achieved wins in battle during the first days of the German invasion, breaking up German infantry formations, liberating captured towns, and overrunning fortified positions.

- The Polish 18th Lancers surprised German troops from the 20th Motorized Infantry Division near the city of Chojnice. Their commander ordered his men to ride straight through the enemy ranks, scattering the Germans, who then returned in armored cars. The Lancers lost 20 out of their 250 men. Afterwards, foreign journalists, seeing the bodies of horses and calvarymen, assumed the Lancers had charged the Panzer tanks.

- Near the end of war came one more charge. The Polish 1st Cavalry attacked a German supply column on the Eastern front on March 1, 1945.

- The final cavalry charge by a US cavalry unit was executed by the 26th Cavalry Regiment of the Philippine Scouts during an encounter with the Japanese in the Bataan Peninsula, Philippines January 16, 1942.

- The final charge of the war by any US mounted forces was conducted by the 3rd Platoon of the 10th Mountain in Italy in April 1945, when they charged a machine gun nest.

WIKIPEDIAHorses in World War II were used by the belligerent nations

They were used for transportation of troops, artillery, materiel, messages, and, to a lesser extent, in mobile cavalry troops. The role of horses for each nation depended on its military doctrines, strategy, and state of economy. It was most pronounced in the German and Soviet Armies. Over the course of the war, Germany (2.75 million) and the Soviet Union (3.5 million) together employed more than six million horses.Most British regular cavalry regiments were mechanised between 1928 and the outbreak of World War II. The United States retained a single horse cavalry regiment stationed in the Philippines, and the German Army retained a single brigade. The French Army of 1939–1940 blended horse regiments into their mobile divisions, and the Soviet Army of 1941 had thirteen cavalry divisions. The Italian, Japanese, Polish and Romanian armies employed substantial cavalry formations.

Horse-drawn transportation was most important for Germany, as it was relatively lacking in automotive industry and oil resources. Infantry and horse-drawn artillery formed the bulk of the German Army throughout the war; only one fifth of the Army belonged to mobile panzer and mechanized divisions. Each German infantry division employed thousands of horses and thousands of men taking care of them. Despite losses of horses to enemy action, exposure and disease, Germany maintained a steady supply of work and saddle horses until 1945. Cavalry in the German Army and the Waffen-SS gradually increased in size, peaking at six cavalry divisions in February 1945.

The Red Army was substantially motorized from 1939 to 1941 but lost most of its war equipment in Operation Barbarossa. The losses were temporarily remedied by forming masses of mounted infantry, which were used as strike forces in the Battle of Moscow. Heavy casualties and a shortage of horses soon compelled the Soviets to reduce the number of cavalry divisions. As tank production and Allied supplies made up for the losses of 1941, the cavalry was merged with tank units, forming more effective strike groups. From 1943 to 1944, cavalry gradually became the mobile infantry component of the tank armies. By the end of the war, Soviet cavalry had been reduced to its prewar strength. The logistical role of horses in the Red Army was not as high as it was in the German Army because of Soviet domestic oil reserves and US truck supplies.

The United States

The United States economy of the interwar period quickly got rid of the obsolete horse; national horse stocks were reduced from 25 million in 1920 to 14 million in 1940.In December 1939, the United States Cavalry consisted of two mechanized and twelve horse regiments of 790 horses each. Chief of Cavalry John K. Herr, a proponent of horse troops ("conservative and downright mossback" according to Allan Millett yet "noble and tragic in his loyalty to horse" according to Roman Jarymowycz), intended to increase them to 1275 horses each. A cavalry division included two brigades of two horse regiments each, eighteen light tanks and a field artillery regiment; the Chief of Artillery leaned to horse and truck traction and dismissed self-propelled artillery to avoid cross-coordination with other branches of service. Cavalry had been the preferred force for the defense of the Mexican border and the Panama Canal Zone from Mexican raiders and enemy landings, a threat that was becoming obsolete in the 1930s, if not for Japan's rising influence. A fleet of horse trailers called portees assisted cavalry in traversing the roads. Once mounted, cavalrymen would reach the battlefield on horseback, dismount and then fight on foot, essentially acting as mobile light infantry.

After the 1940 Louisiana Maneuvers cavalry units were gradually reformed into Armored Corps, starting with Adna R. Chaffee's 1st Armored Corps in July 1940. Another novelty introduced after the maneuvers, the Bantam 4×4 car, soon became known as the jeep and replaced the horse itself. Debates over the integration of armor and horse units continued through 1941 but the failure of these attempts "to marry horse with armor" was evident even to casual civilian observers. The office of Chief of Cavalry was eliminated in March 1942, and the newly formed ground forces began mechanization of the remaining horse units. The 1st Cavalry Division was reorganized as an infantry unit but retained its designation.

The only significant engagement of American horsemen in World War II was the defensive action of the Philippine Scouts (26th Cavalry Regiment). The Scouts challenged the Japanese invaders of Luzon, holding off two armoured and two infantry regiments during the invasion of the Philippines. They repelled a unit of tanks in Binalonan and successfully held ground for the Allied armies' retreat to Bataan. What would become the very last combat horse cavalry charge in U.S. Army history occurred at Morong on the west side of Bataan, on January 16, 1942, when mostly Filipino troopers of 'G' Troop, 26th Cavalry (PS), led by Southern Illinois native 1st Lt. Edwin Ramsey, successfully charged their mounts at a far superior Japanese force of armor-supported infantry, surprising and scattering them. This lightly-armed, 27-man force of U.S. Horse Cavalry, under heavy fire, held off the Japanese for several crucial hours. Ramsey earned a Silver Star and Purple Heart for this action, and the 26th was immortalized in U.S. Cavalry history.

In Europe, the American forces fielded only a few cavalry and supply units during the war. George S. Patton lamented their lack in North Africa and wrote that "had we possessed an American cavalry division with pack artillery in Tunisia and in Sicily, not a German would have escaped".

WIKIPEDIAPart of the Quartermaster Corps

the U.S. Army Remount Service provided horses (and later mules and dogs) as remounts to U.S. Army units. Evolving from both the Remount Service of the Quartermaster Corps and a general horse-breeding program under the control of the Department of Agriculture, the Remount Service began systematically breeding horses for the United States Cavalry in 1918. It remained in operation until 1948, when all animal-breeding programs returned to Department of Agriculture control.Although the need for some sort of remount bureau or office had been recognized since the end of the Civil War, formal steps were not taken, or funding made available, until the first decade of the 20th century. In 1908, the Remount Service was officially activated as part of the Quartermaster Corps with Purchasing Boards set up in Boise, Idaho; Front Royal, Virginia; Lexington, Kentucky; Sheridan, Wyoming; San Angelo, Texas; Colorado Springs, Colorado; and Sacramento, California. These Boards were intended to take the place of the earlier regimental boards. In May of the same year, the Quartermaster Corps took the next logical step and set up the Fort Reno Quartermaster Depot as a "processing/distribution center for military horses and mules".

There was also a determined attempt to engage professional horse breeders in the Remount Service, beginning in 1918 with the approval of a breeding plan for cavalry horses that combined the efforts of the Remount Service with the Bureau of Animal Industry. A 1921 issue of the Cavalry Journal contained an update from the "American Remount Association" calling for owners of "high-class registered Thoroughbreds" to add their stallions to the program. The author also mentioned a reduced-cost registry for "half-breed" Thoroughbreds.

The number of horses involved in the program remained high even into the final years of the Remount Service. As late as 1945, between 450 and 500 stallions owned by the government and over 11,000 civilian-owned mares produced 7,293 foals. Thoroughbreds predominated in the stallion rolls, although a few Morgans, Arabians, and Standardbreds were also used. The number of Arabian stallions increased greatly in 1943 with the addition of the Kellogg Arabian Ranch (renamed the Pomona Remount Depot) to the program.

In 1942, the Remount Service (then called the Remount Division) printed a breakdown of its breeding program in the Cavalry Journal. According to the article, the primary breeding horse was the Thoroughbred (17,983 mares and 688 stallions), followed by Arabians (375 mares and 16 stallions), followed by Morgans, Saddlebreds, Anglo-Arabians, and the Cleveland Bay (trailing with eight mares and one stallion). Of the foals born in 1941, 11,028 of the 11,409 reported were Thoroughbreds.

In 1944, six remount areas (reduced from seven in earlier years) were functioning. These areas served to control both the breeding programs and purchasing functions of the Remount Service and worked in conjunction with the depots. The Areas had headquarters at Front Royal (Virginia), Lexington (Kentucky), Colorado Springs (Colorado), Sheridan (Wyoming), San Angelo (Texas), and Pomona Quartermaster Depot (California)